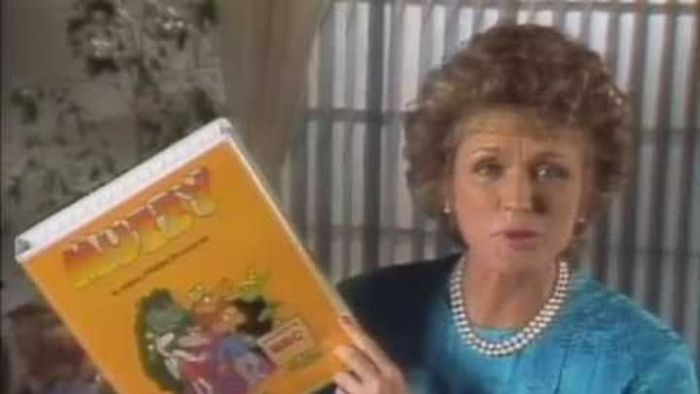

“These kids aren’t French. They’re American.” If you grew up in the early 1990s, this line might ring a bell, along with the unsettling one-minute ad for Muzzy, a quirky green alien with a mission to teach foreign languages to young learners.

The VHS series aimed to teach children languages like Italian, Spanish, French, and German, as chosen by their parents. Kids were captivated by Muzzy’s quirky antics—like devouring clocks and metal objects—while picking up new vocabulary and phrases. For just $28.17 a month over six months (plus shipping), parents could let Muzzy transform their children into bilingual wonders.

However, that wasn’t Muzzy’s initial purpose.

Mastering New Languages

Muzzy began at the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) in 1986 as part of their initiative to engage a worldwide audience with educational resources. With his neutral design, Muzzy had no specific ethnic traits, making him an ideal universal language instructor. For approximately £75 (equivalent to £216 or $272 today), international customers could purchase a 75-minute video and six accompanying workbooks. Muzzy’s mission was to teach English to speakers of Spanish, Japanese, German, Arabic, and other languages.

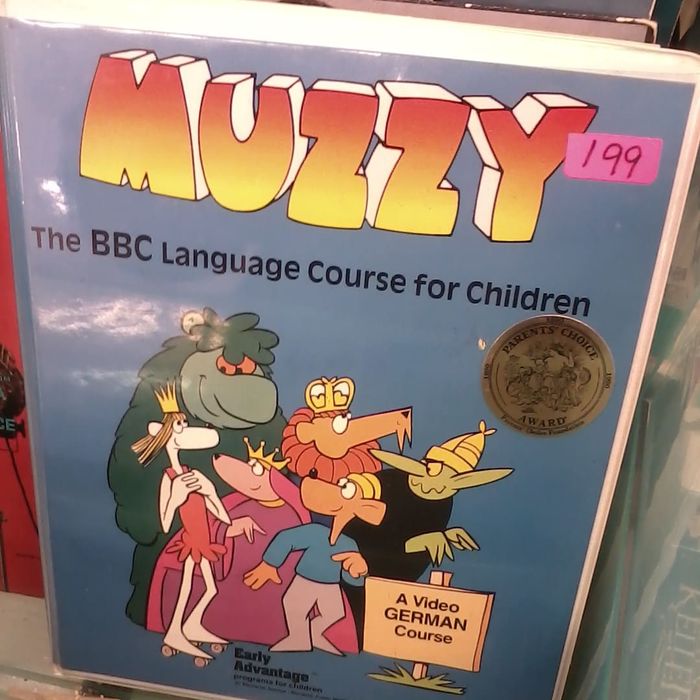

Muzzy's journey to the discount section. | B, Flickr // CC BY 2.0

Muzzy's journey to the discount section. | B, Flickr // CC BY 2.0The animation for the video was created by Richard Taylor, a prominent figure in British animation known for directing the popular educational series “Charley Says.” (In these shorts, Charley might warn children about dangers like playing with matches or speaking to strangers.) Taylor collaborated with producer Joe Hambrook to bring Muzzy to life. The script was written by Wendy Harris, who shared with The Guardian in 1986 that crafting a universally relatable storyline was a challenging task.

“Being completely international is quite challenging, perhaps even impossible,” she remarked.

Nevertheless, the creators of Muzzy gave it their best shot. Officially named Muzzy in Gondoland, the story follows the green extraterrestrial Muzzy as he lands on Earth and gets caught up in a tangled romantic drama involving Princess Sylvia, who is pursued by Bob the Gardener and the king’s sinister scientist, Corvax. Muzzy’s technological skills help rescue the king after he’s trapped inside a computer and defeat Corvax, who creates clones of Sylvia in his obsession. (Sylvia and Bob eventually marry.) Throughout the tale, the characters repeatedly use simple words and phrases like big, small, and garden.

Muzzy is a slow-moving yet friendly character, resembling a mix between Frosty the Snowman and the gremlin tormenting William Shatner in the “Nightmare at 20,000 Feet” episode of The Twilight Zone. For some unexplained reason, Muzzy also has pica, a condition that drives him to eat non-food items like clocks and parking meters. As the story progresses, a human cartoon named Norman interjects with repetitive language drills. (“Good morning.” “Good morning.” “Good morning.” “Good afternoon…”) The monotony is intentional, and without its educational purpose, it might have been unbearable.

Muzzy’s effectiveness as a promoter of the Queen’s English is hard to measure. In 1990, it was reported that Muzzy appeared on Russian TV and had been distributed to 20 countries. It also earned a sequel, 1989’s Muzzy Comes Back. A 1990 Associated Press report noted that the secondary English learning industry was worth $11 billion, with the UK holding a sixth of the market. However, Muzzy’s share of that revenue remains unknown.

What became clearer was the potential to repurpose Muzzy. Instead of teaching English, why not use him to teach foreign languages to Americans? This idea was proposed by BBC sales agent Federico Mallo, who saw untapped potential in the North American market. This led to a direct-mail campaign where Muzzy in Gondoland was re-edited into shorter episodes for various language lessons. The TV and print ads from this campaign introduced Muzzy to most American children in the 1990s.

The BBC emphasized that learning second and third languages would grow in importance over the next few decades. Muzzy offered a way to give children a competitive edge.

“Kids are going to watch TV regardless—four or five hours a day—so why not make some of that time productive?” one advertisement stated. “Muzzy, the BBC’s globally acclaimed audio-video language program, has already provided thousands of children aged 2 to 12 with a significant advantage over those who spend hours watching trivial sitcoms or worse.”

The ad continued, “Muzzy teaches through repetition. Every time your kids watch the kind-hearted Muzzy save Princess Sylvia from the cunning Corvax or assist the king in counting orchard plums, they’ll pick up new words and phrases. Before long, they’ll be speaking Spanish or asking you questions in French.”

Muzzy’s Legacy

In an article on Medium, Mallo shared that marketing Muzzy in the U.S., Spain, and Italy was highly successful, with roughly 22 million copies sold. Over time, Muzzy became a nostalgic icon for many who grew up remembering him as a quirky TV ad without much context.

However, Muzzy has never truly disappeared. In 2005, the course included a complimentary plush Muzzy toy, and in 2013, the BBC revamped him with computer-generated animation. He has also been spotted in costume at various events, such as a 2018 appearance at Indiana’s Duneland Family YMCA.

Yet Muzzy hasn’t been entirely free from controversy. A Reddit user in the r/conspiracy subreddit shared a video featuring Muzzy footage where the English alphabet animation seems to include hidden images, like a castle constructed from human flesh. (These visuals can be seen in the video above when the letter h appears.) Maybe children were justified in being wary of Muzzy. Or, as they might say, peut-être que les enfants avaient raison de se méfier de Muzzy.