When looking at pictures of early branches of humanity's family tree, such as Neanderthals or Homo erectus, you'll notice that modern humans, Homo sapiens, have it relatively easy when it comes to eyebrows. Most early hominins had pronounced, bony brow ridges, in contrast to the smooth brows of today's humans. For years, scientists have debated why these thick ridges were present, and why humans evolved with much smaller brows. A recent study suggests that these heavy brow ridges likely had a social function more important than any physical reason.

Previous studies have proposed that thick brow ridges might have helped connect the eye sockets to the brain, offered protection from physical stress caused by chewing, or even provided some defense against blows to the face.

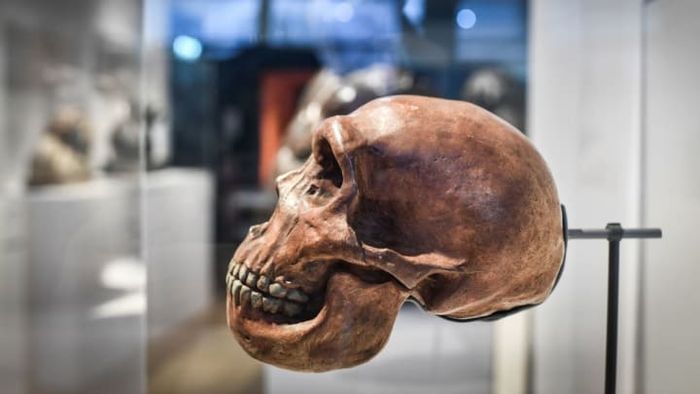

A new study by researchers from the University of York, published in Nature Ecology & Evolution, used a digital model of a fossil skull estimated to be between 125,000 and 300,000 years old. The skull belonged to Homo heidelbergensis, an extinct species that lived between 300,000 and 600,000 years ago in what is now Zambia. The researchers altered the model by adjusting the size of the brow ridge while testing the effects of different bite pressures. They discovered that the brow ridge was much larger than necessary to simply connect the eye sockets to the brain case, and it did not seem to provide protection from biting forces.

Instead, the researchers propose that the brow ridge had a social function. Similar to other primates, such as male mandrills, whose brightly colored, prominent brow ridges act as displays of dominance, early human species may have used their heavy brow ridges in a comparable way.

As Homo sapiens evolved, more subtle forms of communication likely became more important than the obvious social signal of a large brow ridge. With the development of a more vertical forehead, eyebrows became more mobile and nuanced, enabling modern humans to express complex emotions, such as surprise or indignation, through subtle facial movements.

An accompanying analysis in the same journal by Spanish paleontologist Markus Bastir cautions that while the results of the new study are intriguing, they should be viewed with some skepticism. The digital model used in the study was missing a mandible, and a Neanderthal mandible, although from a closely related species, was substituted. This substitution may have affected the analysis of the model and its response to bite forces. Nevertheless, the study offers "exciting prospects for future research," Bastir concludes.