Since the 1980s, Indiana Jones has become the ultimate symbol of adventure, captivating audiences of all ages and even inspiring other fictional characters. With his trademark hat, trusty whip, sharp intellect, and fearless demeanor, all set to an unforgettable musical score, many have fantasized about living a life like Indy’s—exploring the globe in search of priceless treasures. Roy Chapman Andrews came remarkably close to embodying this adventurous spirit. While his exploits didn’t involve supernatural dangers like melting faces or heart extractions, they were nonetheless fraught with peril and often yielded artifacts of immense historical importance.

A Childhood Filled with Adventure

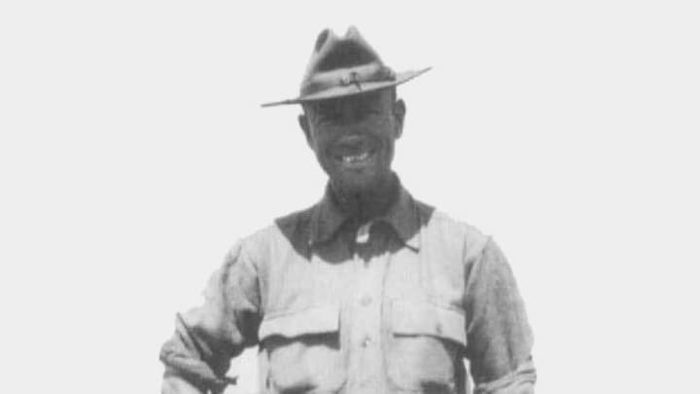

Roy Chapman Andrews Society

Born in Beloit, Wisconsin, in 1884, Roy Chapman Andrews spent his childhood exploring nearby forests and waterways. In his memoir, Under a Lucky Star, he likened himself to “a rabbit, happiest when outdoors.” At the age of nine, he received a single-barrel shotgun, which honed his marksmanship skills as he grew older. Andrews also taught himself taxidermy, a talent he used to fund his education at Beloit College.

From a young age, Andrews dreamed of becoming an explorer, fully aware of the risks involved. However, he could never have anticipated the life-threatening danger he would encounter during a college hunting trip. At 21, while duck hunting on Wisconsin’s Rock River with Montague White, a Beloit College English professor, tragedy struck. It was March, and the icy river, swollen from days of rising water, had treacherous currents. Their boat capsized, throwing both men into the freezing water. Andrews fought the current, eventually clinging to a submerged tree and making it to shore. Sadly, White, despite being a strong swimmer, succumbed to muscle cramps and drowned. This harrowing experience left a profound mark on Andrews, influencing his future adventures and his meticulous approach to safety in his expeditions.

After graduating in 1906, Andrews boarded a train to New York City, determined to fulfill another childhood dream: working at the American Museum of Natural History. Upon arrival, he was told no positions were available. Undeterred, Andrews volunteered to clean the museum’s floors. His persistence paid off, and he was hired to assist in the taxidermy department and support the museum director with various tasks. Despite receiving more lucrative offers, Andrews remained loyal to the museum, quickly advancing to the adventurous fieldwork he had always envisioned.

The Early Career and Perilous Adventures of Andrews

Archive.org

Andrews’ initial passion in the field centered on marine mammals, particularly whales. This interest sparked when, just seven months into his museum tenure, he and colleague Jim Clark were tasked with recovering a whale skeleton from a Long Island beach. The museum director doubted they could succeed, as beached whale bones often sink into the sand rapidly. Against the odds, Andrews and Clark returned with the complete skeleton, having braved a storm and freezing conditions to retrieve it (these bones remain in the museum's department of mammalogy). This achievement inspired Andrews to join numerous expeditions across Alaska, Indonesia, China, Japan, and Korea, where he studied and collected marine mammal specimens. As his career advanced, his research interests broadened, leading him to explore the globe in pursuit of animal specimens and fossils.

Much like the fictional Indiana Jones, Andrews frequently faced life-threatening situations during his travels. In his book On the Trail of Ancient Man, he recounts several near-death experiences from his early career:

“In my first fifteen years of fieldwork, I can recall ten instances where I narrowly escaped death. Two involved nearly drowning in typhoons, one was when a wounded whale charged our boat, another when wild dogs almost attacked my wife and me, and once when we were threatened by fanatical lama priests. I also had close calls after falling off cliffs, nearly being caught by a massive python, and twice narrowly avoiding death at the hands of bandits.”

Discoveries in the Desert

Andrews is most celebrated for his 1920s expeditions in the Gobi Desert. These journeys aimed to comprehensively survey the Central Asian plateau, collecting fossils, live animals, and samples of rocks and vegetation. Henry Fairfield Osborn, the museum’s director, fully supported Andrews, hoping the explorer would uncover evidence for his theory that Central Asia was the cradle of all life on Earth.

Andrews launched his first Gobi Desert expedition in 1922. During this journey, he and his museum colleagues unearthed several complete skeletons of small dinosaurs, along with fragments of larger ones. These were the first dinosaur discoveries made north of the Himalayas in Asia. The team also collected preserved insects, animal remains, and the largest single assemblage of Central Asian mammals, including previously unknown species. Andrews believed these findings only hinted at the vast potential of the Gobi Desert.

Driven by curiosity, Andrews proposed and led multiple follow-up expeditions to delve deeper into the desert’s secrets. His 1923 expedition yielded some of the most significant discoveries of his career. Among these was the skull of a rat-sized mammal that coexisted with dinosaurs—a rare find, as few mammalian skulls from that era had been discovered. Walter Granger, the team’s chief paleontologist, found the skull embedded in Cretaceous sandstone. Initially labeled as an “unidentified reptile,” it was sent to the museum for analysis. In 1925, during Andrews’ third expedition, the team learned the skull belonged to one of the earliest known mammals, sparking excitement and a renewed focus on finding more such remains. They eventually discovered seven additional mammal skulls and skeletal fragments.

The most renowned discovery from Andrews’ expeditions also occurred in 1923. On the second day of setting up camp, George Olsen, a paleontology assistant, reported finding fossil eggs. Though met with skepticism, the team investigated after lunch and confirmed Olsen’s claim—they were dinosaur eggs! Three eggs were exposed, with more embedded in the sandstone. This groundbreaking find confirmed that dinosaurs laid eggs, a fact previously only assumed due to their reptilian nature.

Scientific American

The expedition recovered 25 eggs, suggesting the site was a dinosaur breeding ground. Further investigation revealed a small dinosaur skeleton near the nest, initially thought to be an egg thief and named Oviraptor (egg seizer). However, later discoveries indicated the dinosaur was likely guarding its own eggs.

Andrews discovered that the public was captivated by the dinosaur eggs, overshadowing other expedition findings. Though frustrated by this fixation, he leveraged it to secure funding for future explorations. While wealthy patrons provided some support, it wasn’t sufficient. To encourage public contributions, Andrews and museum director Henry Fairfield Osborn auctioned one of the dinosaur eggs. The publicity campaign included appeals for donations, with Andrews stating in a New York Times article, “We see no reason not to sell one egg, as we have twenty-five. Our goal isn’t profit but to fund the Asiatic expedition.” The auction raised $5,000 from Mr. Austin Colgate, who donated the egg to Colgate University, while public donations totaled $50,000.

Austin Colgate (right) presents Roy Chapman Andrews with a check for the dinosaur egg. Photo courtesy of Colgate University's Geology Department.

Perils in the Desert

Beyond scientific discoveries, Andrews’ Gobi expeditions were fraught with danger. In his memoir Under a Lucky Star, he recounts a harrowing encounter with bandits. While driving down a steep slope, Andrews spotted four armed men on horseback below. Unable to turn back, he accelerated toward them, startling their horses. The panicked animals bolted, leaving one bandit stranded. Andrews fired shots at the man’s hat, chasing him away, later admitting the bobbing hat was “too tempting to resist.”

Another chilling incident involved venomous pit vipers invading the team’s camp. Seeking warmth on a cold night, the snakes slithered into the tents. Motor engineer Norman Lovell awoke to find one crossing a moonlit patch in his tent. Before stepping down, he spotted two more coiled around his bedposts and another near his cot, narrowly avoiding a deadly encounter.

Lovell wasn’t the sole team member to face vipers. Many others discovered snakes concealed in their boots, hats, and even among their rifles. Thankfully, the cold weather rendered the snakes sluggish, reducing their threat. The team killed 47 snakes that night, emerging unharmed but far more cautious. Andrews later recounted how he screamed in terror after stepping on something soft and round, only to find it was a coiled rope. This incident solidified his shared aversion to snakes with Indiana Jones.

Andrews Bids Farewell to the Gobi

Wikimedia Commons

Andrews believed the Gobi Desert still held many secrets, but political tensions in Mongolia and China halted expeditions after 1930. His team faced severe restrictions on their work and data collection, alongside heightened dangers from bandits and hostile locals.

Although this chapter of Andrews’ career ended, a new one began in 1934 when he became director of the American Museum of Natural History. He held this role until January 1, 1942, when he passed the torch to a younger generation. Post-retirement, Andrews and his wife Yvette relocated to California, where he spent his remaining years chronicling his adventures. He passed away from a heart attack in 1960.

Was Andrews the Real-Life Inspiration for Indiana Jones?

Many believe Andrews served as the inspiration for the iconic adventurer Dr. Henry Jones Jr. While George Lucas never explicitly named Andrews as a direct influence, it’s known that Lucas drew heavily from the adventure serials of the 1940s and 1950s he enjoyed as a child. These serials, in turn, likely took cues from the scientists and explorers of Andrews’ era. Andrews, renowned for his Gobi Desert expeditions, stands out as one of the most famous figures of his time, significantly advancing scientific exploration. Though the connection is indirect, many are convinced Andrews influenced the whip-carrying professor. Notably, Andrews always wore a ranger hat during his expeditions, much like Indy’s iconic fedora.

The Enduring Legacy of Andrews

Beyond being likened to Indiana Jones, Andrews left a lasting impact through the Roy Chapman Andrews Society, established in 1999 in his hometown of Beloit. The society aims to honor Andrews’ contributions and raise awareness of his groundbreaking work. Annually, it presents the Distinguished Explorer Award (DEA) to individuals who have made significant scientific discoveries. This year’s recipient was Dr. John Grotzinger, recognized for his leadership in the Mars Curiosity mission.

Sources: The Roy Chapman Andrews Society; Unmuseum.org; Beloit University.