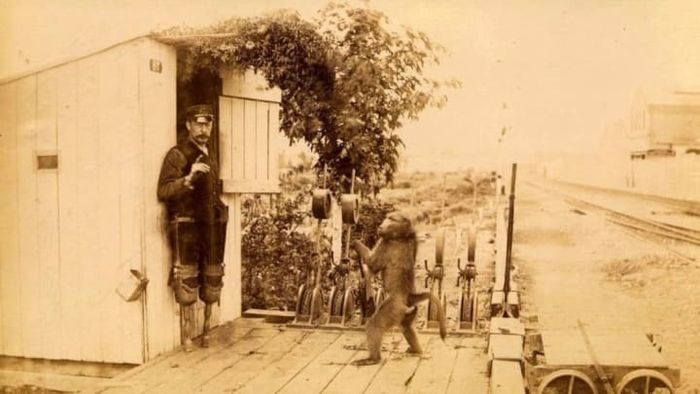

During the 1880s, James Edwin Wide, a railway signalman with a peg leg, encountered an extraordinary sight at a lively South African market: a chacma baboon expertly steering an oxcart. Amazed by the animal's abilities, Wide purchased the baboon, named him Jack, and took him in as both a pet and a helper.

Wide required assistance due to a prior work accident that cost him both legs, making his daily half-mile journey to the train station a significant challenge. He trained Jack to transport him to and from work in a small trolley. Over time, Jack also began assisting with domestic tasks, such as sweeping floors and disposing of garbage.

Jack's true talent emerged in the signal box. When trains neared the rail switches at Uitenhage station, they would sound their whistles in specific sequences to indicate which tracks needed adjustment. Observing his owner, Jack learned the patterns and began operating the levers independently.

Before long, Wide could sit back and unwind while his furry assistant took over the task of switching the rails. According to The Railway Signal, Wide “taught the baboon so well that he could relax in his cabin, working on tasks like stuffing birds, while the animal, tethered outside, handled all the levers and switches.”

As the tale goes, a well-to-do train passenger once spotted a baboon operating the controls instead of a human and reported it to railway officials. Instead of dismissing Wide, the managers chose to test the baboon’s skills. They were left utterly amazed by the results.

“Jack understands the signal whistle just as well as I do, along with every lever,” wrote railway superintendent George B. Howe, who observed the baboon around 1890. “It was heartwarming to witness his affection for his master. As I approached, they were both seated on the trolley. The baboon had his arms around Wide’s neck, gently stroking his face.”

Jack was reportedly assigned an official employee number and earned 20 cents daily, along with half a bottle of beer each week. He died in 1890 after contracting tuberculosis. For nine years, Jack operated the railway switches flawlessly—proof that perfectionism isn’t exclusive to humans.