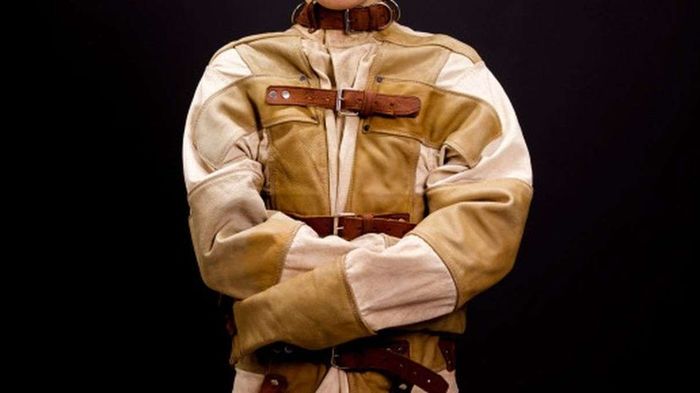

Modern mental health institutions rarely utilize straitjackets, as they now possess more advanced methods to ensure patient safety. Peter Dazeley/Photographer's Choice/Getty Images

Modern mental health institutions rarely utilize straitjackets, as they now possess more advanced methods to ensure patient safety. Peter Dazeley/Photographer's Choice/Getty ImagesIn media, a patient in a straitjacket sways in a grim asylum setting, while a horror movie character dons one to evoke fear. These depictions cement straitjackets as symbols of terror and madness.

In reality, straitjackets are seldom seen, especially in psychiatric care settings. Viewed as outdated, they have been largely replaced by alternative methods to protect patients and others from harm.

Physical restraints are now a last resort. Mental health facilities employ improved strategies such as medication, de-escalation techniques, and adequate staffing to maintain safety, according to Dr. Steven K. Hoge, a Columbia University Medical School professor and chair of the American Psychiatric Association's Council on Psychiatry and the Law.

Today, facilities and medical professionals adhere to a different philosophy, Hoge explains. Restraints are now seen as a violation of patient rights, a concern that has grown significantly since the 1970s, exemplified by Jack Nicholson's character being restrained for electroconvulsive therapy in the 1975 adaptation of "One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest."

1975: A still from the film "One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest" shows actor Jack Nicholson being held down by an orderly. Republic Pictures/Stringer/Getty Images

1975: A still from the film "One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest" shows actor Jack Nicholson being held down by an orderly. Republic Pictures/Stringer/Getty ImagesWith nearly 35 years of experience, including at Bellevue Hospital's high-security mental health unit in New York City, Hoge has never encountered or heard of a straitjacket being used to restrain a patient.

"This is akin to using leeches," he remarks. "It would be noteworthy and unusual."

Why do straitjackets continue to captivate public interest? They evoke a sense of intrigue. The mere thought of being confined in one—arms crossed, sleeves fastened behind—can trigger a claustrophobic reaction even in those who aren't typically prone to it.

Despite low sales, straitjackets are still manufactured and utilized in specific cases: for an Ohio man suffering from Alzheimer's, an 8-year-old autistic child in Tennessee, and an inmate in a Kentucky county jail.

However, for manufacturers, this represents a niche market.

"We're talking fewer than 100 units annually," explains Stacy Schultz, general manager of Humane Restraint in Waunakee, Wisconsin. The company also produces ankle and wrist restraints, transport hoods, and 'suicide smocks'—clothing designed to prevent tearing or rolling.

According to Schultz, straitjackets are primarily purchased by 'custodial facilities' such as jails and prisons.

According to psychiatrist Hoge, if straitjackets are still in use today, they are most likely found in jails and prisons. These facilities, referred to as America's 'new asylums' by the Treatment Advocacy Center in 2014, house ten times more individuals with serious mental illnesses than state psychiatric hospitals. Hoge notes that such institutions often lack adequate mental health resources and staffing and rarely adhere to hospital standards.

"Prisons often employ practices that are unheard of in standard mental health facilities," he states.

The American Bar Association has acknowledged this issue. Its Standards on Treatment of Prisoners, established in 2010, explicitly prohibit the use of physical restraints as a form of punishment in correctional facilities.

The list of prohibited mechanical devices includes leg irons, handcuffs, spit masks, and straitjackets.

In the 1800s, doctors, often baffled by mental illness, attributed it to various causes, including sunstroke and excessive novel reading, as documented by the Kansas Historical Society.