Long before tools like electromagnetic field detectors and infrared thermometers became staples in paranormal investigations, Shirley Jackson portrayed ghost hunting as a scientific pursuit in her novel, The Haunting of Hill House. The story begins with Dr. John Montague, a man of science, inviting participants to spend the summer in a reputedly haunted mansion. His goal is to document undeniable proof of the supernatural, though he refrains from declaring Hill House haunted without concrete evidence.

Jackson’s innovative take on the traditional ghost story breathed new life into the genre in 1959. However, her portrayal of a methodical paranormal investigator wasn’t entirely fictional. Dr. Montague was inspired by real-life figures, including Nandor Fodor, a parapsychologist whose controversial work alienated spiritualists, won acclaim from Sigmund Freud, and even caught the interest of Hollywood.

Explaining the Unexplainable

Alma Fielding was in dire need of answers. Starting in early 1938, the 34-year-old homemaker from Thornton Heath, a London suburb, reported bizarre occurrences in her home. She spoke of glasses hurling themselves across rooms and objects like watches mysteriously moving between her pockets. Unexplained scratch marks began appearing on her back. While her husband and son also witnessed these events, Alma seemed to be the focal point. Rings she had lost would inexplicably appear on her fingers while shopping, and small animals would suddenly materialize on her lap during car rides.

It was uncertain whether the situation called for a medium or a psychologist. Luckily, Nandor Fodor had expertise in both fields.

By the time Fodor met Alma, he had already spent years deeply involved in the paranormal community. Born in Hungary in 1895, he experienced a supernatural event as a child, which influenced his lifelong career. He worked as a journalist in London and New York, writing about paranormal topics for spiritualist publications such as the British journal Light. His most notable work was the Encyclopaedia of Psychic Science, a 400-page book praised as an invaluable resource for psychic researchers and a fascinating read for curious minds.

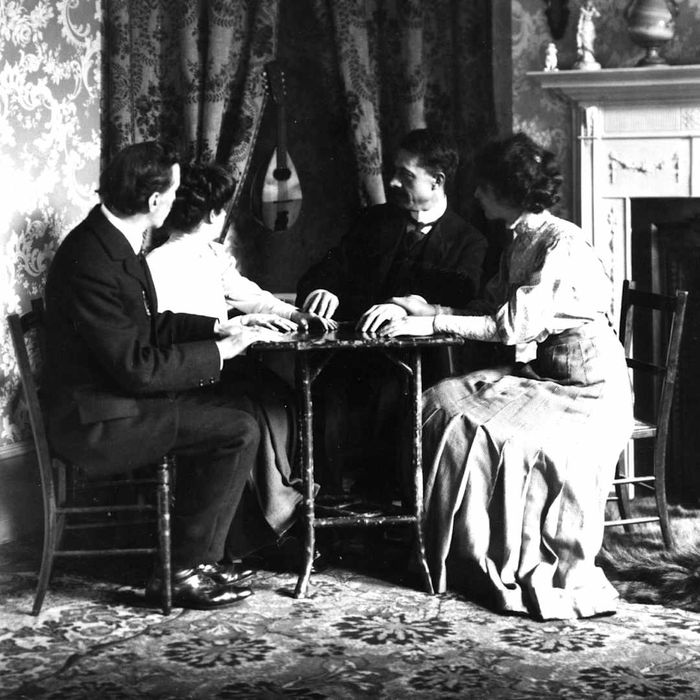

Seances were a widely popular spiritualist practice during the 1920s and '30s. | Mills/Stringer/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Seances were a widely popular spiritualist practice during the 1920s and '30s. | Mills/Stringer/Hulton Archive/Getty ImagesFodor found no shortage of interest in his work. Spiritualism was experiencing a resurgence in the 1920s and '30s, with many groups dedicated to exploring the supernatural. Fodor was an active member of several such organizations, including the Ghost Club and the London Spiritualist Alliance. He eventually left journalism to focus entirely on this field, and by 1938, he had become a research officer at the International Institute for Psychical Research.

Despite his high standing in spiritualist circles, Fodor often diverged from his peers. He approached alleged paranormal cases with a skeptical eye, unlike many spiritualists who resisted new ideas. Fodor saw the paranormal as an uncharted territory ripe for exploration. Living in an age of technological breakthroughs, he was frustrated by the lack of progress in spiritualism. In a 1934 article for the Leicester Evening Mail, he wrote, 'We no longer believe in technical impossibilities, yet when it comes to psychological discoveries or the hidden powers of the human soul, we rush to defend outdated beliefs.'

Fodor was unafraid to break new ground in his field. This boldness led him to entertain theories that challenged conventional wisdom, such as his belief that so-called 'ghostly' phenomena might not involve ghosts at all.

A Peculiar Poltergeist

Fodor was captivated by newspaper accounts of Alma Fielding’s haunting. Journalists described the mysterious force hurling eggs down hallways and smashing saucers as a poltergeist—a non-physical entity capable of interacting with the physical world, often in violent ways. Intrigued by such phenomena, Fodor decided to delve into her case.

Before meeting Fielding, Fodor suspected her experiences might not be caused by ghosts. During the same period that spiritualism was resurging in Britain, psychology was undergoing significant changes. Freud’s theories about the unconscious mind and its expression through involuntary actions had gained traction. Fodor, an admirer of Freud’s work on repressed memories and their psychological impact, expanded on this idea. He theorized that unresolved trauma might not only affect the mind but also manifest in the external world. If true, such psychic disturbances could explain the strange occurrences Fielding reported in Thornton Heath.

Despite already having a theory, Fodor approached Fielding’s case with the precision of a scientist in a more conventional field. He brought her to the International Institute for Psychical Research in London, where she was subjected to cameras, voice recorders, and X-ray machines. According to his records, Fielding provided ample data for analysis. Fodor photographed scratches on her arms, allegedly caused by a ghostly tiger, and puncture wounds on her throat, which she claimed were from a winged creature. When she asserted that a spirit had impregnated her overnight, Fodor observed her abdomen swelling. Other institute members reportedly witnessed objects like a mouse, a beetle, a bird, a lamp, and a brooch appearing out of thin air during these sessions.

X-rays revealed that Fielding had concealed some of the objects on her person or inside her body, confirming Fodor’s suspicion that her case lacked any supernatural elements. While he noted that she was 'ruining her case by fraud,' Fodor concluded that the events demonstrated the extraordinary power of the unconscious mind, supporting his theory.

Fodor observed that Fielding entered a trance-like state during the strange occurrences, leading him to believe the phenomena stemmed from her unconscious mind rather than external forces. He theorized that her life’s traumas—such as losing children and battling severe health issues—were causing her to unconsciously manifest these disturbances.

Fodor’s conclusions were met with resistance. When the institute’s members discovered he was pursuing a psychoanalytical explanation instead of a paranormal one, they were appalled. His radical ideas contradicted the organization’s mission, leading to his expulsion.

While spiritualists rejected Fodor, psychoanalysts welcomed his work. After his expulsion, Fodor’s wife Irene personally delivered his report on the psychic poltergeist to Freud. In a letter, Freud praised Fodor’s psychological approach to studying the medium, calling it 'the right steps.' He found Fodor’s conclusions 'very probable,' providing the validation Fodor needed to continue his groundbreaking research.

In 1958, two decades after the events, Fodor released a book called On the Trail of the Poltergeist, detailing the Thornton Heath case. In it, he contended that evaluating Fielding through society’s logical and ethical frameworks was misguided:

“A dissociated woman isn’t necessarily guided by ethics or logic. She isn’t driven by socially accepted instincts but by her unconscious mind, which operates under its own rules. By uncovering evidence of deliberate fraud in these phenomena, we’ve only scratched the surface of the issues arising from her dissociation. Since dissociation stems from psychological trauma, leading to both objective and subjective psychic events, it falls within the scope of psychical research to delve deeper. In fact, it’s essential if we aim to comprehend the case. If a psychological cause underpinned the phenomena, it’s entirely possible that, for our subject, a fraudulent event held the same significance as a genuine one. Her unconscious mind wouldn’t care about psychical research or evidence. It would focus solely on its own struggles, perhaps conserving the energy at its disposal.”

Fodor’s theory in On the Trail of the Poltergeist didn’t replace ghosts in popular imagination, but it received significant recognition from the literary community the following year.

Ghost in the Machine

Despite its title, The Haunting of Hill House diverges from traditional haunted house stories. While the mansion initially appears to be the epicenter of the strange occurrences, it becomes evident that the haunting is tied to—and possibly driven by—one specific character. Eleanor Vance, grappling with personal demons and a stifling home life, finds her inner turmoil mirrored by the escalating supernatural chaos around her.

Richard Johnson, Claire Bloom, and Russ Tamblyn on the set of 'The Haunting' (1963). | Sunset Boulevard/Royalty-free/Getty Images

Richard Johnson, Claire Bloom, and Russ Tamblyn on the set of 'The Haunting' (1963). | Sunset Boulevard/Royalty-free/Getty ImagesThe tale of a young woman tormented by a poltergeist and subjected to a scientific paranormal investigation would resonate with anyone familiar with Fodor’s work before reading Hill House. Like Fodor, Jackson explored the idea that psychological disturbances could manifest as supernatural phenomena in the physical world. While scientific evidence for this concept was scarce, its effectiveness as a literary tool was unquestionable.

Though the novel shares striking similarities with the Alma Fielding case, Jackson’s initial inspiration came from elsewhere. The idea for Hill House began when she read about 19th-century psychic researchers who, as she later wrote, 'rented a haunted house and documented their experiences. Yet, the true story that emerged wasn’t about the house but about the people involved—earnest, perhaps misguided, but determined individuals with diverse motivations. I wanted to create my own haunted house, populate it with my characters, and see what I could make happen.' A dilapidated building she glimpsed from a train to New York City further fueled her imagination.

In 1958, while working on the novel, Jackson came across news reports about a Long Island family plagued by an alleged poltergeist. Similar to Fielding, the Herrmanns witnessed objects moving inexplicably in their home, with the activity centered around one family member—preteen Jimmy Herrmann. This case not only influenced Hill House but also served as the inspiration for the movie Poltergeist 24 years later.

An article discussing the connection between psychic energy and poltergeist activity referenced Haunted People, a book co-authored by Nandor Fodor and his colleague Hereward Carrington. Shirley Jackson turned to this book to delve deeper into the theory.

In her biography Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life, Ruth Franklin notes that even if Jackson hadn’t admitted it, the influence of Haunted People is unmistakable. Many elements in the book are directly drawn from Fodor’s research, such as the mysterious rain of stones Eleanor encountered at age 12. Franklin highlights that this phenomenon is the 'most frequent characteristic of a poltergeist manifestation' documented in Haunted People: 'The majority of poltergeist cases in the book share a common thread—one that recurs repeatedly and is instantly recognizable to readers of Hill House.'

Four years after its publication, The Haunting of Hill House was adapted into a film. The production team sought an advisor to add authenticity to the supernatural narrative, and Nandor Fodor was the natural choice. As the film’s consultant, Fodor met Jackson and inquired about her inspiration. She confirmed his suspicions: she had indeed read his works on parapsychology, and they had clearly left a lasting impression.

Both Fodor and Jackson passed away soon after the film’s release—Fodor in 1964 and Jackson the following year. While they left behind remarkable legacies, they are most celebrated for redefining the ghost story genre, replacing traditional specters with the terrors of the human psyche.