Deafness has been part of the human experience for centuries. Deaf individuals have long created intricate communication systems. In fact, historical evidence suggests that early forms of sign language may have existed before spoken language. Studies show that sign languages were in use as early as the 4th century BC, but it took millennia for them to develop into the forms we recognize today.

Sign languages are now used by millions of people across the globe, with over 70 million users. These languages, like their spoken counterparts, reflect the unique cultures and vocabularies of different regions. The significance of sign languages has grown over time, with the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities advocating for their recognition as equal to spoken languages in official settings. The UN also designated September 23 as the International Day of Sign Languages.

Despite their current prominence, the journey of sign language has not been without challenges. The deaf community faced widespread discrimination for centuries. Many linguists and political figures underestimated or rejected the value of sign languages. However, over time, these misconceptions were debunked. The following are ten fascinating facts about the history of sign language development.

10. The Role of Socrates and the Ancient Greeks in Sign Language

More than two thousand years ago, Plato authored Cratylus, where the concept of deafness was already a significant subject. This dialogue, written in the fifth century BC, narrates a discussion between Socrates and two companions. They delve into the role of names and words. At one point, Socrates emphasizes the importance of creating 'signs by moving our hands, head, and the rest of our body.' He demonstrates the movement of a horse as an example, miming the animal's actions to describe it without uttering a word.

Historians today highlight this passage as evidence that the ancient Greeks used a primitive form of sign language. However, the communication practices were not entirely developed. Other research suggests the Greeks thought educating deaf people was impossible, and thus, for centuries, they did not attempt it. Even notable philosophers held negative views of the deaf. Aristotle, for example, famously stated that deaf people were 'senseless and incapable of reason.'

Fortunately, not everyone shared this bleak view. Still, it would take many centuries for sign language to evolve and gain the form we know today.

9. The Expansion of Sign Language Among Native American Tribes

There are currently over three dozen distinct American Indian Sign Languages, each reflecting the unique communication styles of various tribes. These languages have existed for a long time, with Europeans first recording 'hand talk' among Native Americans in 1542. Some early scholars suggested that Native Americans only used hand gestures to communicate with European settlers. However, modern experts agree that these hand signals were in use well before the arrival of Europeans.

The most famous American Indian Sign Language (AISL) is Plains Indian Sign Language (PISL). Deaf individuals were highly skilled in using this language, but it wasn't limited to them. Hunters, wanting to stay silent around their prey, adopted these signs for communication. Native people traveling long distances for trade between tribes also used it. Even well-known Americans took advantage of this unique form of communication.

During the Lewis and Clark expedition across the American West, the explorers utilized the Plains Indian Sign Language to communicate. Although various Indigenous groups spoke different languages, the sign language served as a shared method of interaction.

Unfortunately, Plains Indian Sign Language is now in decline. The Oklahoma Museum of Natural History classifies it as an 'endangered' language. With few fluent signers remaining, however, community leaders on reservations are hopeful that the language might experience a revival.

8. Europeans Begin to Shift Their Views on Deafness

By the 16th century, scholars in Europe had moved beyond the ancient Greek perspectives on deaf individuals. One of the most influential figures in this shift was Dutch scholar and writer Rudolf Agricola. In 1521, he published his work De Inventione Dialectica (On Dialectical Invention). Agricola made the case that deaf individuals were fully capable of acquiring a language.

Girolamo Cardano, an Italian physician, was deeply influenced by Agricola's ideas. This was especially personal for Cardano, as his own son was deaf. The doctor began teaching his son hand signs that corresponded to Italian words, and the approach proved successful in helping the boy communicate. Cardano's efforts extended beyond his son's education, culminating in the publication of his own book in 1575, which focused on the education of deaf people, their literacy, and their intellectual potential. By this time, more scholars were recognizing the importance and effectiveness of sign language.

At the close of the 15th century, a German physician named Solomon Alberti made a groundbreaking contribution to the understanding of deaf culture and language development. He asserted that deaf individuals were capable of reading both written words and lip movements. Alberti also strongly emphasized the intelligence of deaf people. His assertion that they could master a language and receive an education opened the door to further studies. By the end of the 16th century, it was widely accepted that deaf individuals could acquire language and create their own sign language systems.

7. The Monk Who Was Determined to Move Hand Signing Forward

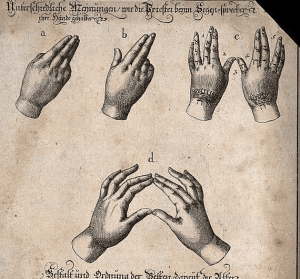

While Agricola, Cardano, and Alberti were making strides in academic research related to deafness, monks across Europe were focusing on other crucial tasks. A key area of their attention was the development of hand-signing and fingerspelling. Although many of these monks were not deaf, they had taken vows of silence, which made hand communication essential for their daily lives.

It is believed that some monks began to develop complex hand gestures as early as the eighth century. However, the 1500s marked a pivotal period when these gestures began to spread beyond monastic communities. These devout individuals recognized the potential of their sign language and began teaching hand signals and fingerspelling to deaf children.

One notable Spanish monk, Fray Melchor de Yebra, took things a step further. In 1593, he published the first book that included illustrations and diagrams for fingerspelling the alphabet. His goal was to attract deaf individuals to Catholicism and to allow priests to communicate with people who could no longer speak in their final moments. However, the reach and influence of the diagrams went far beyond their original religious intent.

By 1620, Juan Pablo Bonet, a teacher of deaf children, adapted and expanded the diagrams to make them more widely accessible. Deaf children began to learn fingerspelling and sign language in large numbers, sparking the growth of a standardized form of non-verbal communication.

6. Deaf Servants Find Success in the Ottoman Empire

As sign language began to be formalized across Western Europe, rulers in other parts of the world had already recognized its potential as a form of non-verbal communication. In the Ottoman Empire, sultans specifically hired deaf servants for their ability to communicate silently. These servants used hand signs for political purposes within royal courts and high society gatherings. The signs were intricate and subtle, ideal for secretive sultans worried about confidential information leaking from the empire.

In their desire for secrecy and security, Ottoman rulers also took the time to learn sign language. European travelers were fascinated by how Ottoman elites used it in their daily lives. Sir Paul Rycaut, a historian from the 17th century, marveled at how the sultans had “perfect[ed] themselves in the language of the Mutes.” In his 1665 book on the empire, he mentioned that there were at least 100 deaf servants working in the high court. Political leaders appreciated the confidentiality of the complex signs, which allowed sultans to “speak” privately with their deaf servants, hidden behind curtains or around corners, without worrying that others would overhear sensitive discussions.

While many ancient cultures, including the Greeks, viewed deafness as a disadvantage, the Ottomans considered it a hidden blessing.

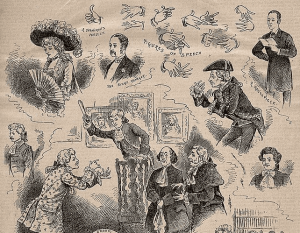

5. Sign Language Becomes Commonplace in England

The 1593 fingerspelling guide by de Yebra marked a crucial turning point for the deaf community. Fast forward 51 years, and in 1644, another groundbreaking advancement took place. English doctor John Bulwer published Chirologia, or, The naturall language of the hand, where he examined non-verbal forms of communication. Bulwer argued that the hand 'speaks all languages,' transcending the 'formal differences' of spoken language. In the book, he also detailed universal hand gestures, such as placing a hand on the chest to show sadness, wagging a finger to express disapproval, and using the middle finger to 'chastise men.'

However, Bulwer’s work extended far beyond these gestures. He highlighted the significance of a finger alphabet and a non-verbal number system. Bulwer advocated for streamlining hand communication by creating standardized methods. The book also featured elaborate diagrams of alphabet letters and hand signals, which, though simple compared to modern sign language, closely resemble contemporary sign expressions. Thanks to its wide appeal, Chirologia played a significant role in promoting the use of consistent hand signals across Europe. By the mid-17th century, sign language had gained considerable momentum on the continent.

4. A French Priest Steps Up to Standardize Signs

Building on Bulwer's work, French Catholic priest Charles-Michel de l’Épée sought to standardize sign language. He adapted an ancient non-verbal communication system used in France, now known as 'Old French Sign Language.' By incorporating Bulwer’s ideas, de l’Épée established a clear system of signs to convey common ideas. He also helped refine the alphabet spelling system used by deaf people throughout Europe, and his work has withstood the test of time.

Today, linguists recognize de l’Épée’s efforts as the foundation of both French and American sign languages. Not only did he standardize signs, but de l’Épée also established a school for the deaf, which remains operational today as the National Institute of Young Deaf of Paris. Additionally, he created a dictionary, which was completed after his death. His pioneering work earned him the title 'Father of the Deaf.' Fortunately, de l’Épée was not alone in advocating for the deaf community.

In 1779, Pierre Desloge, a Frenchman, published a book that passionately advocated for sign language as the proper method to educate those who could not hear. Desloge, a Parisian bookbinder, was not just an author, but also deaf himself, bringing a unique personal insight into his work. Today, historians speculate that his book might have been the first mass-produced work penned by a deaf author.

3. Sign Language (Finally!) Flourishes in the Modern Era

By the 1960s, American Sign Language had become well-established. However, it faced resistance from linguists, and oralists still held much influence in academic circles. Manualists interested in ASL were often sidelined. This began to change in the 1960s when William Stokoe, a professor at Gallaudet, set out to study the linguistics of sign language. He secured a grant from the National Science Foundation to support his research, and despite harsh criticism from oralist scholars, Stokoe persisted. The NSF backed his grant, and his work became a landmark in the field.

In 1965, Stokoe published Dictionary of American Sign Language on Linguistic Principles, which quickly transformed deaf education in the United States. Teachers began to embrace the manualist approach, and ASL flourished as a result. Building on Stokoe's foundation, Clayton Valli, another professor at Gallaudet, published The Gallaudet Dictionary of American Sign Language in 2006. It is now one of the most comprehensive and widely used ASL reference works, featuring thousands of illustrations, etymological sources, and a detailed index.

Today, sign language has spread far beyond its roots in France and the United States. In East Asia, millions have learned sign language, and China has made significant strides in standardizing various dialects of sign language. In the 2010s, the Chinese government undertook a large-scale effort to create unified standards for Chinese Sign Language. In 2018, these new standards were released, encompassing over 5,000 commonly used words that correspond to the country's spoken language characters.

2. Troubling Talk Amid American Sign Language Opponents

As American Sign Language was becoming more standardized, concerns arose about its potential cultural consequences. The debate escalated throughout the 19th century, with manualists like Gallaudet advocating for the importance of ASL, while oralists argued that deaf individuals should focus on lip-reading and speech rather than signing.

Oralism received a significant endorsement in 1880 during the International Congress of Educators of the Deaf held in Milan, Italy. At the conference, deaf educators were excluded, and the oralists present were able to argue unchallenged that lip-reading and speech were far superior to sign language as a means of communication for deaf students.

Today, we recognize that lip-reading is a useful tool for many deaf individuals, especially those who lose their hearing later in life. However, the 1880 conference didn't take that into account. The oralists gained significant influence at the event, and their methods became dominant in deaf education for years. Many schools shifted to oralist teaching techniques and even banned deaf teachers, which made it harder for students to connect with their instructors.

One of the most vocal supporters of oralism was Alexander Graham Bell, the famed inventor of the telephone. Bell spent years debating Gallaudet’s manualist supporters, though his personal connection to the deaf community—his wife and mother were both deaf—didn't stop him from taking controversial stances. Bell believed that deafness posed a threat to American identity, and at one point, he even argued that deaf people should be prohibited from marrying or having children. Despite his family ties, Bell advocated for the complete elimination of sign language and sought to ban deaf teachers from schools.

Today, the oralist viewpoint championed by Bell has clearly lost the debate. However, the lasting impact of his public criticism of the deaf community as 'defective' continues to linger. Deaf individuals, regardless of their abilities, still face a pervasive cultural stigma, one that often shapes perceptions of them in a negative light.

1. The Birth of American Sign Language

The influence of France’s Charles-Michel de l’Épée catalyzed progress among scholars in other countries, paving the way for the development of American Sign Language (ASL) in the early 1800s. Inspired by the success of the French system, a minister named Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet began teaching the alphabet to his deaf neighbor, Alice Cogswell. Encouraged by her progress, Gallaudet sought to expand educational opportunities for other deaf children. In 1817, he established the American School for the Deaf in Hartford, Connecticut.

At Gallaudet’s institution, the foundation for ASL was laid by adapting de l’Épée’s French model for English speakers. As pioneers like Gallaudet refined the language, ASL quickly evolved into a unique form of communication, separate from its French counterpart. By 1830, ASL had become the dominant signing system in America. Just like de l’Épée’s legacy in France, Gallaudet’s work became foundational to the American deaf community, ensuring his contributions would never be forgotten.

In 1864, President Abraham Lincoln signed a historic bill establishing the National Deaf-Mute College in Washington, D.C., a groundbreaking institution for deaf students at the time. Today, the college continues to thrive as Gallaudet University, the world’s only accredited university for deaf students, maintaining a reputation of excellence.