May 10, 1933, stands as one of the darkest and most chilling moments in the history of free speech within Western Civilization. On this day, the newly empowered Nazi Party orchestrated a massive book-burning event, supported by university students and broadcast across German radio stations, at Bebelplatz near the Berlin Opera House. Approximately 25,000 books labeled as 'un-German' were set ablaze in a haunting act that foreshadowed the suppression of the authors and ideologies they embodied.

10. All Quiet on the Western Front (Erich Remarque)

Or perhaps we should refer to it as 'Im Westen Nichts Neues'? This German phrase, meaning 'In the West, Nothing New,' serves as the original title of the novel penned by Erich Maria Remarque, a veteran of World War I.

The 1929 novel, which quickly became a classic, saw its 1930 American film adaptation make history as the first movie based on a novel to win the Academy Award for Best Picture. This achievement cemented the translated phrase as a symbol of stagnation and infuriated Adolf Hitler to no end.

Hitler, who held the rank of Lance Corporal in the Kaiser’s army during World War I, had little interest in revisiting Germany’s humiliating defeat unless it fueled his narrative of vengeance against the perceived injustices imposed by the 1918 Armistice. Notably, when he overran France in 1940, Hitler deliberately chose the same railway carriage where Germany had surrendered to the Allies 22 years earlier for the formal surrender ceremony.

Rather than glorifying the German soldier, Remarque exposed the brutal physical and psychological toll endured by troops in the trenches of World War I, as well as the alienation many experienced upon reintegrating into civilian life. All Quiet was groundbreaking not for its portrayal of war’s horrors—a well-known reality—but for its exploration of the unsettling transition to post-war normalcy. It stands as one of the earliest detailed accounts of what we now identify as military-related post-traumatic stress disorder.

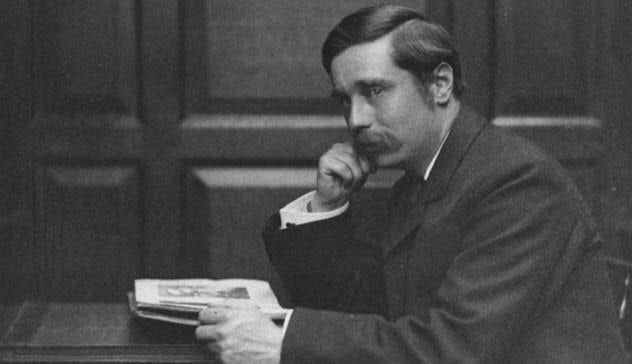

9. The Outline of History (H.G. Wells)

Why did a 19th-century science fiction author find his work among Hitler’s burned books? Because one of his nonfiction works directly contradicted a fundamental principle of Nazi ideology.

Though Wells is best remembered for classics like The Time Machine (1895), War of the Worlds (1897), and The Invisible Man (also 1897), his most ambitious project emerged over two decades later. In 1919, he launched a paperback series titled The Outline of History, ambitiously subtitled The Whole Story of Man. This monumental work spanned over 1,300 pages, chronicling everything from the origins of Earth (Chapter 1: “The Origins of Earth”) to the contemporary era (Chapter 39: “The Great War”).

Wells’s motivation was straightforward: he believed history textbooks were subpar and thought he could improve them. He aimed to connect human history through recurring themes, viewing it as a journey toward a shared purpose, often interrupted by nomadic tribes conquering established civilizations. He also highlighted the evolution of 'free intelligence,' citing figures like Herodotus as milestones in the expansion of human thought.

However, it was Wells’s progressive stance on race that made The Outline of History a target for the flames. He outright dismissed notions of racial or civilizational dominance, stating that humanity is 'an animal species in a state of arrested differentiation and possible admixture,' and that claims of Western intellectual superiority 'dissolve into thin air.'

8. The Metamorphosis (Franz Kafka)

“One morning, as Gregor Samsa awoke from troubled dreams, he discovered he had been transformed into a gigantic insect in his bed.”

Driven by one of literature’s most iconic opening lines, The Metamorphosis is a novella rich with allegorical depth, exploring themes such as the dehumanizing pressures of modern life, the clash between individuality and societal structures, and the often transactional nature of human relationships.

The Nazis rejected these themes entirely, as their ideology emphasized selfless devotion to Germany, rooted in a belief in racial superiority (e.g., 'We can endure hardship for the Fatherland because we are inherently superior.'). The Metamorphosis offered no such glorification of collective duty or an idealized society.

Additionally, the novella was penned by a Jewish author, a fact that Hitler and his regime found particularly objectionable.

When Gregor’s family realizes his transformation is irreversible, they confine him to a room, strip away his treasured possessions, and gradually isolate him. His sister, Grete, initially cares for him, but even her compassion and dedication begin to fade over time.

Ultimately, Grete shifts from being Gregor’s sole advocate to his primary critic, advocating for his removal and driving him to starve himself to death. Many interpret Grete’s transformation as the most profound metamorphosis in the story, as she evolves from a compassionate, selfless individual into someone cold and pragmatic—a reflection of societal expectations. In many ways, she embodies the traits the Nazis idealized.

7. Heart of Darkness (Joseph Conrad)

During the late 19th century, European powers engaged in the Scramble for Africa, a frenzied competition to colonize the so-called Dark Continent. Amid this exploitative frenzy, which persisted until World War I, Polish-English author Joseph Conrad wrote a haunting, gradually intensifying novel about an expedition into the Congo Free State.

First published in 1899, Heart of Darkness follows Charles Marlow, a ferry captain hired by a Belgian trading company to venture into the remote depths of Africa. As he progresses, the journey grows increasingly unsettling. Early on, he encounters a railroad project where African workers are left to perish, symbolizing the brutal exploitation of colonialism.

Marlow learns of the enigmatic Mr. Kurtz and travels 200 miles to Central Station, where his riverboat is supposed to be waiting. Instead, he finds it damaged, and the repairs take months, during which his fascination with Kurtz deepens. Eventually, the crew sets off on a two-month voyage downriver, only to be ambushed by natives just before reaching Kurtz’s Inner Station.

The natives, it turns out, were protecting Kurtz, whom they revered as a near-deity. This reverence persisted despite—or perhaps because of—his gruesome practice of decapitating them and displaying their heads on poles. The novel’s vivid symbolism served as a stark critique of Europe’s racist exploitation of Africa and its people. Unsurprisingly, Hitler opposed such narratives that exposed the moral corruption of conquest, colonization, and murderous arrogance.

6. “How I Became a Socialist” (Helen Keller Essay)

The Nazis’ literary purges extended beyond books to include newspapers that published views opposing Nazi ideology. Among these was the now-defunct New York Call, which featured an essay by Helen Keller on November 2, 1912. Keller, who became a symbol of resilience despite losing her sight and hearing as a child, used her platform to advocate for progressive causes.

By 1912, Keller had already gained widespread recognition, having published her extraordinary memoir, The Story of My Life, during her time at Radcliffe College. The book chronicled her incredible journey from near-total isolation to becoming a remarkably articulate writer. A year later, she made history as the first deaf-blind individual to earn a degree from Radcliffe.

As she grew older, Keller emerged as a vocal advocate for women’s suffrage, pacifism, and workers’ rights. Her 1912 essay in the New York Call sought to articulate the reasons behind her strong support for socialist ideals.

Keller’s works might have escaped the flames had it not been for another essay she published two decades later. On May 9, 1933—just before the mass book burnings—Keller addressed German students in an open letter published in The New York Times. She wrote, 'History has taught you nothing if you think you can kill ideas. Tyrants have tried to do that often before, and the ideas have risen up in their might and destroyed them.'

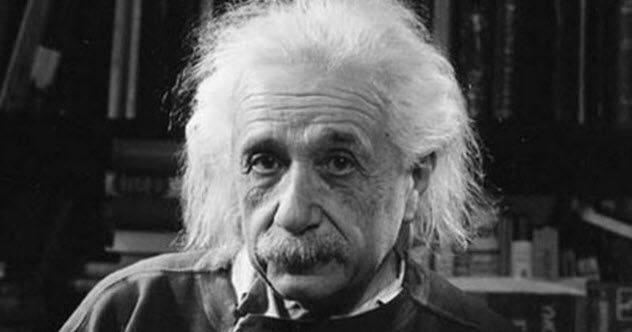

5. Cosmic Religion (Albert Einstein)

In late 1930, one of Germany’s most brilliant minds was questioned about the rising Nazi Party, which had recently secured over 18% of the vote in parliamentary elections, making it the second-largest political group.

“I am not acquainted with Herr Hitler,” remarked the man who would later become a global symbol of genius. “Once economic conditions stabilize, his influence will diminish.” He also downplayed the party’s virulent anti-Semitism, stating, “While Jewish solidarity is always necessary, any exaggerated response to the election results would be unwarranted.”

Even Albert Einstein, it seems, could occasionally misjudge a situation.

Hitler’s animosity toward Einstein went beyond his Jewish identity. Had Einstein confined himself to academia, his 1915 Theory of Relativity might not have provoked enough controversy to warrant destruction. However, Einstein was a vocal pacifist, a stance he adopted as early as 1914 when he refused to sign a manifesto supported by numerous German intellectuals that justified Germany’s militaristic actions preceding World War I.

Einstein’s perspectives on religion posed an even greater challenge to Nazi propaganda. In his 1931 work, Cosmic Religion, Einstein explains that his spirituality is rooted in science rather than traditional religious beliefs. By rejecting the notion of a meddling deity, he directly contradicted Nazi ideology, which relied on the idea of a predestined Third Reich destined for global supremacy.

Fortunately, Einstein was in the United States when Hitler ascended to power in 1933. He chose to remain there, leaving Hitler to lament the loss of one of history’s greatest minds.

4. Unnamed Artwork Compilations (Otto Dix)

Hitler’s passion for art is well-documented, though his taste was questionable. As his forces conquered Europe, he plundered some of the world’s most prestigious museums, amassing a vast collection of stolen masterpieces.

Unsurprisingly, if artwork failed to align with Hitler’s ideals, it was condemned rather than celebrated. Consequently, many of the books burned at Bebelplatz were compilations of works by influential artists—essentially coffee table books—that Hitler considered immoral, excessively decadent, or contrary to German nationalism.

One such artist was Otto Dix, a German painter and printmaker renowned for his unflinching portrayals of war and society during the Weimar Republic era. A prime example is his 1932 triptych The War, which vividly depicts a ravaged cityscape littered with remnants of battle and human remains. Fortunately, the original painting survived the war, as the May 10 burnings primarily targeted printed reproductions rather than physical artworks.

Hitler’s persecution of Dix didn’t end there. In 1933, the Nazis expelled him from his teaching post at the Dresden Academy. Four years later, they included his works in the infamous “Degenerate Art” exhibition in Munich, designed to showcase art deemed unacceptable in the Third Reich. Despite the oppression, Dix chose to remain in Germany and was later conscripted into the Nazi army at the age of 53.

3. Everything (Institute of Sexology)

In the early 20th century, Germany was a leader in progressive tolerance. Quite surprising, given later events.

Established in 1919 by Magnus Hirschfeld, a pioneer in the field of sexology, Germany’s Institute of Sexology became known for its progressive efforts to promote equality for women and LGBTQ+ individuals, as well as its groundbreaking research on transsexuality. Hirschfeld also campaigned to abolish Paragraph 175, a law that criminalized homosexuality in Germany.

Predictably, Hitler found none of this acceptable. Hirschfeld’s identity as a gay, Jewish, and liberal individual made him a triple threat in the eyes of the Nazis. On May 6, 1933, just days before the infamous book burnings, Nazi-aligned students stormed and occupied the Institute (pictured above). Whether they received extra credit for this remains unclear.

In the days that followed, the Institute’s extensive collection of texts was transported to the book-burning site, where they were consumed by flames on May 10. Hirschfeld, who was in Paris at the time, learned of the destruction through a newsreel. Among the works destroyed was Heinrich Heine’s Almansor, which famously warned, 'Where they burn books, they will ultimately burn people.'

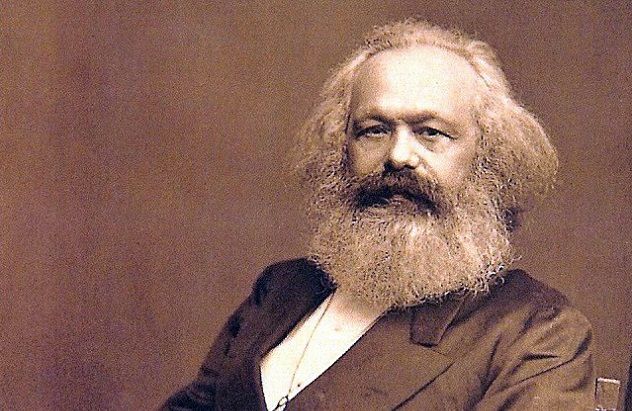

2. The Communist Manifesto (Karl Marx & Friedrich Engels)

Hitler’s disdain for communism is widely recognized, but the reasons behind it are less clear. Despite the Nazi Party’s name (National Socialist Workers’ Party) suggesting socialist leanings, the two ideologies share some economic similarities. However, Hitler’s animosity toward communism, particularly Soviet communism, was deeply personal rather than purely ideological.

In the 1920s, Nazi ideologue Alfred Rosenberg introduced Hitler to the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, one of history’s most infamous antisemitic works. This fabricated text claimed to outline a Jewish conspiracy for global domination, fueling Hitler’s existing prejudices and paranoia.

Hitler’s delusional worldview led him to see enemies everywhere. Observing the significant Jewish involvement in Russia’s 1917–1923 Bolshevik Revolution, he became convinced it marked the start of a Jewish plot to dominate Europe.

Despite its radical reputation, The Communist Manifesto is relatively measured in tone. Marx and Engels analyze society through the lens of class struggle, dividing it into “Bourgeois and Proletarians”—the wealthy elite and the working class. They argue that “the history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles,” emphasizing how divisions within the working class benefit the ruling elite by maintaining the status quo.

Many of the manifesto’s proposals, considered revolutionary at the time, have since become foundational elements of modern Western society. These include progressive taxation, the elimination of child labor, free public education, and the establishment of publicly owned land.

1. A Brave New World (Aldous Huxley)

Don’t mess with Henry Ford—he was Hitler’s idol.

Even without its jabs at Hitler’s favorite American, Huxley’s 1932 novel was destined for the flames. A stark literary warning against conformity and authoritarianism, A Brave New World presents a dystopian vision filled with technologies Hitler would have eagerly embraced. From genetic manipulation in artificial wombs and childhood conditioning through a rigid caste system to mood-altering drugs ensuring public compliance, the novel reads like a blueprint for a regime aspiring to last a millennium.

Huxley also critiques racial arrogance. When the protagonist travels to the southwestern United States, they visit a “Savage Reservation,” witnessing the so-called flaws of natural life, such as aging, multilingualism, and religion—essentially, the raw essence of humanity.