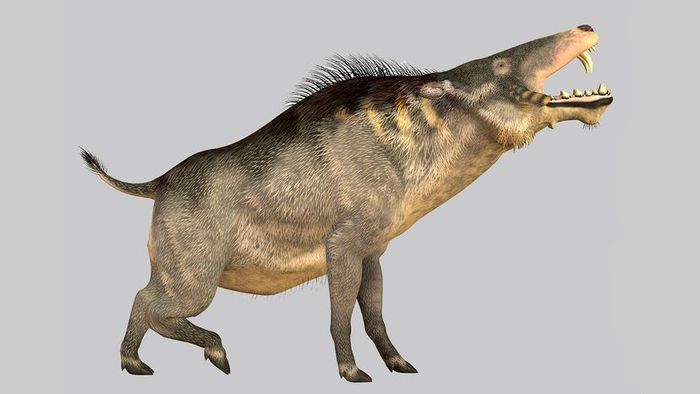

Often referred to as hell pigs, entelodonts thrived across Eurasia, North America, and Africa for millions of years. Stocktrek Images/Getty Images

Often referred to as hell pigs, entelodonts thrived across Eurasia, North America, and Africa for millions of years. Stocktrek Images/Getty ImagesKey Insights

- Ancient "hell pigs," known as entelodonts, inhabited North America and Eurasia between 37 and 16 million years ago, displaying features similar to pigs and hippos.

- These omnivores possessed strong jaws and massive teeth, enabling them to consume both vegetation and meat.

- Although they looked fearsome, entelodonts were not actual pigs but part of the extinct Entelodontidae family of mammals.

The discovery appeared to resemble a meat storage site. In 1999, the Society for Vertebrate Paleontology received a report about an unusual bonebed discovered near Douglas, Wyoming. The fossilized remains of at least six Poebrotherium camels were found clustered together. These ancient camels, unlike their modern hump-backed relatives, were relatively small, comparable in size to domestic sheep. The fossils at this site date back approximately 33.4 million years, during the early Oligocene Epoch.

Many of the Poebrotherium specimens preserved their skulls, necks, rib cages, and forelimbs. However, the hind legs and hips — the camels' meaty hindquarters — were absent. Additionally, the bones bore distinctive tooth marks. This evidence implies that the pile of camel remains might have served as a prehistoric storage site, where predators dragged and stored their prey.

An examination of the region's fossil record reveals the presence of a formidable predator from that era, whose teeth align perfectly with the bite marks found. This creature, known as Archaeotherium, weighed an estimated 600 pounds (270 kilograms) and stood 4.5 feet (1.4 meters) tall at the shoulder. With cloven hooves, slender legs, bony jaw protrusions, and a long snout filled with powerful teeth, it would have been an awe-inspiring sight.

Archaeotherium was part of a group of omnivorous creatures that roamed Eurasia, North America, and Africa for millions of years: the fearsome entelodonts.

Nightmare Fuel

Entelodonts have earned some truly remarkable nicknames, often referred to as "hell pigs" or "terminator pigs." Despite their pig-like appearance, these creatures were not actually pigs.

There has been ongoing debate about their classification within the mammalian family tree. While it's universally accepted that entelodonts were artiodactyls—a group that includes whales and even-toed ungulates like camels, goats, and hippos—their specific placement remains contested. Earlier theories suggested pigs and peccaries as their closest living relatives, but this view has shifted. A 2009 study proposed that entelodonts were more closely related to hippos, whales, and the extinct predator Andrewsarchus.

Over 50 species of entelodonts have been identified. The oldest known species, Eoentelodon yunanense, was a pig-sized creature that roamed China approximately 38 million years ago. Soon after, entelodonts migrated to North America.

Early entelodont species typically had short snouts, but over millions of years, evolution extended their jaws. While they began as relatively small animals, larger species quickly emerged. Archaeotherium, discussed earlier, was among the first sizable entelodonts, though it was far from the largest.

As recently as 18 million years ago, the North American Great Plains were inhabited by the massive Daeodon. Standing nearly 7 feet (2.1 meters) tall at the shoulder, this colossal creature may have weighed over 930 pounds (431 kilograms).

The skull of Daeodon measured an impressive 3 feet (0.91 meters) in length. To bear the weight of its massive head, the animal possessed strong neck muscles attached to prominent vertebral arches near its shoulders. This suggests it may have had a noticeable hump, similar to that of a bison or white rhino.

Form and Function

The mouth of an entelodont featured a unique combination of elongated canine tusks and flat cheek teeth, a configuration not seen in any living mammal. Based on the structure of the snout and the areas where jaw muscles were attached, it's evident that these creatures could open their jaws extremely wide.

The size of the muscle attachment points indicates that larger, long-snouted "hell pigs" possessed incredibly strong bites. A 1990 study on their feeding mechanics revealed that entelodonts could crush food by forcefully closing their jaws vertically. Additionally, they could grind food using their blunt back teeth by moving their jaws side to side.

Similar to modern pigs, entelodonts were undoubtedly omnivores. Wear patterns on their teeth indicate they frequently chewed on bones. Paleontologists believe these animals were skilled scavengers and likely hunted live prey. Their diet also likely included tough roots, eggs, fruits, and various plants.

Entelodont teeth served purposes beyond eating. Deep gouges and puncture marks, some as deep as 0.78 inches (2 centimeters), have been discovered on entelodont skulls. These injuries, including healed scratches and wounds around their eyes, suggest they engaged in fierce face-biting battles with one another.

For many territorial mammals, intimidating rivals is crucial. This might explain why entelodonts had prominent, flaring cheekbones extending from their skulls. (Another theory suggests these structures served as muscle attachment points.) Additionally, many species featured bony knobs, or "tubercles," on their lower jaws, which may have been used in combat.

The last entelodonts vanished around 16 million years ago. While the exact cause of their extinction remains unknown, the rise of new mammalian predators, such as the extinct "bear dogs," may have played a role.

The term "entelodont" originates from the Greek words enteles ("perfect" or "complete") and odontos ("tooth/teeth"). Thus, one interpretation of "entelodont" is "perfect tooth."