In the mid-1990s, Apple Inc. was on the verge of collapse, but it managed to achieve one of the most impressive comebacks in business history. With the launch of iconic products like the iMac, iPod, iPhone, and iPad, Apple regained its position at the forefront of the tech world. Despite criticism that it lacked true innovation and relied too heavily on Steve Jobs’s legacy after his passing in 2011, Apple remains one of the most profitable companies globally, with an enormous cash reserve.

However, Apple has had its share of blunders along the way—failed products and poor management decisions, both with and without Steve Jobs. Let’s explore the 10 biggest missteps in Apple’s history.

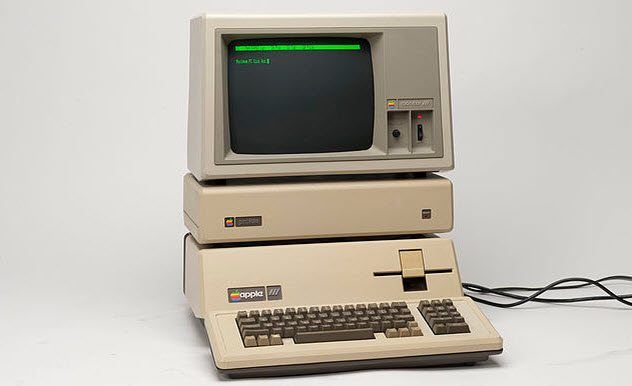

10. Apple III

At the close of every Apple press release, the company proudly claims credit for pioneering the personal computer revolution with the Apple II in the 1970s. Even their fiercest competitors are unlikely to dispute this assertion. However, by 1980, Apple realized that to sustain its initial success, it had to break into the business market, especially with IBM, a long-established mainframe giant, developing its first personal computer.

The Apple III was conceived in response to these market challenges. With the established reputation of the Apple II brand and several innovative features—such as a fanless design for quieter operation and the option for 512 KB of memory (unheard of at the time)—the Apple III was expected to thrive. But upon its release in the fall of 1980, Apple was about to face its first major failure.

The Apple III's price tag was a significant hindrance to its success. Depending on the configuration, the computer ranged in price from $3,495 to $4,995—astronomically high for a personal computer in 1980 (or even in 2017).

The decision to exclude a fan led to the Apple III overheating, causing chips to become dislodged and rendering the machine inoperable. In a bizarre and ineffective tech support move, Apple suggested that users lift the machine 5 centimeters (2 inches) into the air and drop it to reseat the chips.

With its sky-high price, malfunctioning units, and absurd tech “fix,” the Apple III was doomed to a swift demise based solely on its reputation. It marked Apple's first major flop, but certainly not the last.

9. The ‘Hockey Puck Mouse’

Apple has long been praised for its dedication to not only the technology behind its products but also their visual design. When Steve Jobs unveiled the first iMac in 1998, it marked the beginning of a new era in computer aesthetics. The era of dull beige boxes was over; colorful, translucent plastics became the norm. This design theme even carried over to the iMac's round mouse. Jobs hailed it as 'the best mouse ever created,' but even before the iMac was released, many were skeptical.

The so-called 'hockey puck mouse' was certainly eye-catching, but it proved to be frustrating in everyday use. Its small size and odd shape led to hand cramps, and its round form made it nearly impossible to tell if it was oriented correctly. (A later revision added a notch to the top, so users could feel the right side.)

Almost immediately, the market demanded two new solutions. One was a snap-on piece of plastic that transformed the iMac’s mouse into a more familiar shape. The other was a range of new mice that maintained the translucent plastic style but adopted traditional designs.

Apple eventually discontinued the 'hockey puck' mouse and replaced it with newer models like the Mighty Mouse and the Apple Magic Mouse.

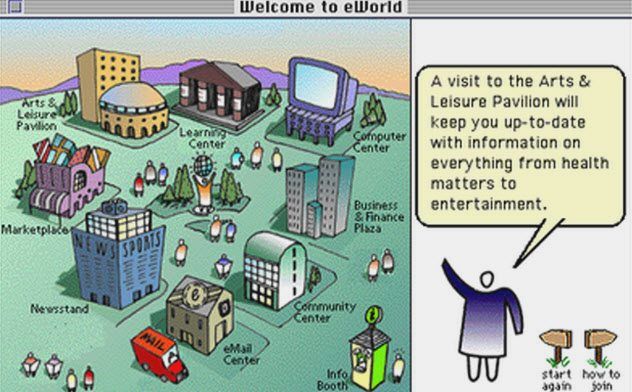

8. eWorld

When the Internet was first opened to the public, many newcomers were unaware that all they needed was an Internet connection and a web browser to get online. This ignorance helped services like AOL thrive, as they not only offered dial-up Internet access but also included user-friendly applications to help navigate the sprawling 'net.

Apple made a disastrous attempt to compete with AOL by launching eWorld, which introduced a 'village' concept for the Internet. However, high dial-up fees and eWorld’s exclusive compatibility with Macs (at a time when 95% of computers ran Windows) spelled its inevitable failure.

Launched in June 1994, eWorld was discontinued by March 1996. Subscribers who tried to launch the application after that time were met with a message informing them that eWorld was no longer available.

7. Mac Clones

Microsoft Windows secured its dominance in the desktop market by running not only on IBM's PCs but also on the multitude of IBM-compatible clones that began flooding the market in the 1980s.

Apple took a different approach: if you wanted to use the Mac OS (operating system), you had to buy a Mac. Starting in the mid-1980s, there were pushes from within Apple to either develop a version of the Mac OS for IBM-compatible PCs or, following IBM’s lead, allow Apple’s hardware to be cloned.

These ideas were repeatedly shot down until 1994, when Apple found itself in serious financial trouble. In 1995, Apple decided to try the clone strategy and granted Mac OS licenses to the clone maker Power Computing. Other companies, including Motorola and UMAX, also jumped on board, licensing the Mac OS.

Unfortunately for Apple, their attempt to replicate Microsoft’s success with this strategy backfired. The clone program only ended up cannibalizing the sales of Apple’s own Macs, with the company receiving only a small licensing fee for the Mac OS instead of the substantial profit margins from selling its own hardware.

When Steve Jobs returned to Apple in 1997, he immediately sought to extricate the company from the clone agreements made during his absence. The contracts were easily bypassed, as they only allowed clone companies to distribute versions of Mac OS 7.

Jobs took an internal project originally planned as Mac OS 7.7 and rebranded it as Mac OS 8. By 1997, the brief era of Mac clones had come to an end. However, the damage was already done, as Apple had lost millions in hardware sales when it needed the revenue the most.

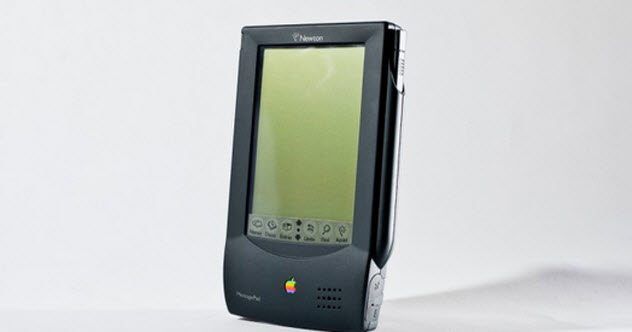

6. Newton

The Newton series of personal digital assistants (PDAs), a pet project of former Apple CEO John Sculley, is often remembered as a major embarrassment for the company. While many of the Newton models were innovative for their time, they were marred by one significant flaw.

Before the Palm Pilot PDAs of the late 1990s and the smartphones of today, the Newtons were among the first capable handheld computers. However, the flagship feature—the ability to convert handwriting into text using a stylus—was far from ready for prime time.

The mistakes in the handwriting-to-text conversion were so frequent and comical that the feature was mocked in places like the Doonesbury comic strip, on Saturday Night Live, and even in an episode of The Simpsons.

When Steve Jobs returned to Apple, he quickly terminated the Newton line, just as he did with the Mac clones. With the launch of the iPhone and iPad, Apple was able to restore its reputation in the world of mobile devices.

5. PowerMac G4 Cube

Listing the PowerMac G4 Cube among Apple’s failures might upset some Apple enthusiasts. This sleek, elegantly designed desktop computer still has a loyal following, even 18 years after its release. It even found a place in the New York Museum of Modern Art.

However, Apple misjudged how much consumers would be willing to pay for aesthetics. The base model, priced at $1,799 (without a monitor), was available at the same time as the more powerful, much more expandable PowerMac G4 tower, which cost $200 less. Many customers who wanted the Cube opted to wait until it hit the second-hand market, where it was priced closer to its actual technical value.

Launched in July 2000, Apple quickly realized the Cube was not selling as expected and discontinued it just a year later, in July 2001.

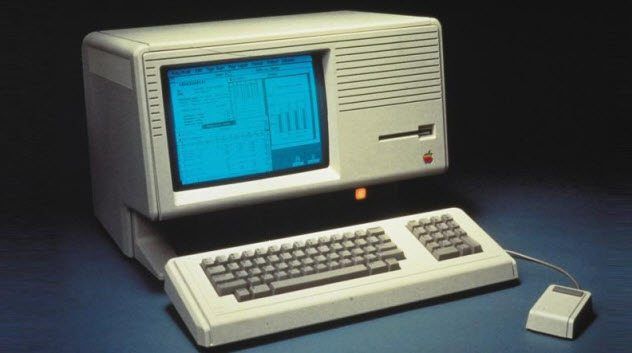

4. Lisa

Today’s computers all use a graphical user interface (GUI), meaning our screens feature icons that we can click or tap. Files and directories are represented by icons of folders and documents.

However, before the era of graphical interfaces, computers mostly used text-based interfaces. You interacted with the system via a command prompt, typing in commands to run programs, most of which were text-based (with a few simple graphics). While many credit the first Mac, launched in January 1984, as Apple’s first GUI-powered computer, the Lisa, which also used a similar interface, actually debuted a full year earlier in January 1983.

Despite being groundbreaking for its time, the Lisa was held back by two significant issues. First, like the earlier Apple III, it was prohibitively expensive, retailing for $9,995 for the base model—roughly $25,000 in today’s money. Secondly, it was slow, running on a modest 5 MHz Motorola 68000 processor. Those in the know were also aware that Apple was working on the Mac, which was expected to be faster and more affordable.

Sure enough, a year later, the Mac was released with the same 68000 processor, but this time running at 8 MHz—offering a 60 percent performance boost over the Lisa. It didn’t take long for consumers to realize that the Mac was a far better deal. Existing Lisa units in stock were modified to run Mac software and rebranded as the 'Macintosh XL.' Those that still couldn’t find buyers were eventually sent to the landfill.

3. Lemmings Commercial

At the Mac’s January 1984 launch, Apple unveiled the groundbreaking commercial ‘1984,’ which also aired during that year’s Super Bowl. Directed by the legendary Ridley Scott, this commercial has since become iconic. Advertising Age even ranked it as one of the greatest ads of all time.

For its follow-up, Apple teamed up with its advertising agency, Chiat/Day, to buy another Super Bowl ad spot in 1985. Ridley Scott wasn’t available this time, so his brother Tony Scott took the helm for the new commercial, 'Lemmings.' This ad was meant to promote the 'Macintosh Office,' not a product itself, but a suite of technologies that allowed Macs to be networked for easy file and printer sharing.

The ‘Lemmings’ ad depicted a group of businesspeople in suits, each following the other blindly, walking off a cliff. The voice-over, promising the Macintosh Office, had the last person stop in their tracks. Whereas '1984' had been dark yet inspiring, 'Lemmings' was often seen as patronizing and off-putting to the very audience Apple was trying to appeal to.

After producing the 'greatest commercial of all time,' the new ad marked the beginning of a challenging phase for Apple. By the year’s end, Steve Jobs had left the company, and Microsoft had begun its ascent to dominance with Windows running on every IBM-compatible PC. Despite a few victories along the way, Apple didn’t fully regain its footing until Jobs introduced the iMac in 1998.

2. Copland

After the success of the Mac and its GUI in 1984, Apple found itself in a difficult position. Users adored the Mac OS, which was groundbreaking at the time. But technology was advancing quickly, much like it does today.

Apple needed to stay current with modern standards but was reluctant to alter the beloved Mac OS too drastically. Instead, the company spent an entire 17 years patching and updating the Mac OS code to try to keep up. Eventually, Apple released the much more modern Mac OS X in 2001.

Copland was an internal initiative aimed at delivering a new OS that included modern features while maintaining compatibility with the classic Mac OS. Among its new capabilities were true multiuser support and protected memory, which would prevent a single application crash from taking down the whole system. The project began in 1994, but only one preview release for developers was made available in 1996.

After spending millions of dollars on the project, Apple’s then-CEO Gil Amelio effectively ended it when he chose to acquire an existing OS that could be adapted to serve as the new Mac OS. Apple bought Steve Jobs’s NeXT, which included the highly regarded OpenStep OS (previously called NeXTSTEP), bringing Jobs back to Apple after the 1985 boardroom coup that had forced his departure.

While Copland might be a name known only to true Mac enthusiasts, the millions spent on the project and Apple’s failure at that time to create its own modern OS make Copland one of the company’s greatest missteps.

1. Pippin

Never heard of the Pippin? You’re not alone—many outside of Japan have never come across it. This was Apple’s cautious attempt to enter the gaming console market. Instead of creating a new, dedicated console, Apple repurposed the internals of the Macintosh Classic II, shaping it to resemble a gaming device and adding a game controller.

It’s difficult to pinpoint Apple’s exact goal with the Pippin. Perhaps it was an attempt to encourage game developers to create more titles for the Mac. Or maybe it was a way to dip its toes into the console market using existing hardware, avoiding the cost of developing a new platform. Regardless, Apple was cautious with the initiative, initially testing it only in Japan.

Once the Pippin was overtaken by fierce competition from systems like the Nintendo 64, Apple pulled the plug on the console. It briefly hit the U.S. market in June 1996, but by the following year, it had disappeared from both U.S. and Japanese store shelves.