Human beings have always held a unique admiration for the earliest examples of our creativity and intellect. As we've discussed previously, the artifacts we create distinguish us from other species, and we take great pride in them. Unearthing an artifact that can be claimed as 'the first,' or at least the oldest one in existence, holds profound meaning.

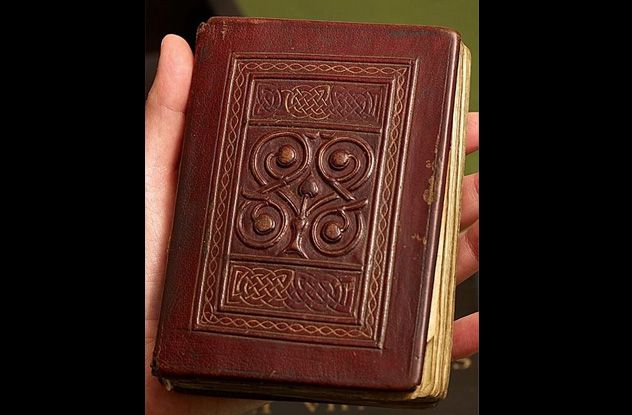

10. The Oldest Surviving European Manuscript

What is the oldest surviving book in the world? Since the very concept of a book has been a subject of debate since the earliest days of literature, answering this question is no easy task and could very well take up an entire article.

However, the oldest surviving European bound book, the kind we are all familiar with today, is the St. Cuthbert Gospel (also known as the Stonyhurst Gospel or the St. Cuthbert Gospel of St. John). This red, leather-bound, illuminated gospel was written in Latin during the seventh century.

In 2012, the British Library in London acquired this book for a staggering $14 million from the Jesuit community in Belgium, following the most successful fundraising campaign in the nation's history. A fully digitized version is now accessible online.

The book is a copy of the Gospel of St. John, originally created in northeastern England for Saint Cuthbert and placed into his coffin over 1,300 years ago after his death. When Vikings began raiding the northeast coast of England, St. Cuthbert’s monastic community relocated from Lindisfarne Island, taking the coffin with them. The book was preserved after they settled in Durham. In 1104, when a new shrine for the saint was being constructed, the coffin was opened, revealing the book, which was then safeguarded, passing hands until it was eventually transferred to the Jesuits.

9. The Oldest Known Official Coin

Before coins were issued by the state, early coin-like objects were created by wealthy merchants and powerful members of society. Some of these items were used as trade goods, while others signified rank. Although there is some debate, most experts agree that the first true coin was the Lydian one-third stater, or trite, minted by King Alyattes in Lydia, Asia Minor (modern-day Turkey). It features a bold carving of a roaring lion’s head on one side and a double-square incuse punch made by a hammer during the minting process on the other side. This punch mark is the imprint from the hammer used to press the coin onto the die, and it was also believed to indicate the coin's purity.

The coin is made from electrum, a naturally occurring gold-silver alloy that is harder than pure gold. Known in the ancient world as 'white gold,' it was commonly used in trade. The use of these coins spread to ancient Greece, and from there, they helped establish coinage throughout the Western world. The Lydian one-third stater is believed to have been equivalent to about a month’s salary at the time.

These coins were minted between 660 and 600 B.C., and by the standards of coin collectors, they aren't particularly rare (you can buy one for around $1,000–2,000). However, there are much rarer denominations with variations in lion images, punches, and weights, including the Lydian stater (14 grams), sixth stater (2.35 grams), and twelfth stater (1.18 grams).

8. The Oldest Surviving Wooden Structure

The oldest surviving wooden buildings are located at the Buddhist Horyu-ji Temple in Ikaruga, Nara Prefecture, Japan. Four buildings from the temple still stand, dating back to Japan's Asuka period.

Construction of the temple began in A.D. 587, commissioned by Emperor Yomei, who sought divine intervention to recover from an illness. At that time, Kyoto had not yet become the capital, and Buddhism was still a relatively new religion in Japan.

After Emperor Yomei's death, his successor, Empress Suiko, along with her regent Prince Shotoku, completed the temple's construction in A.D. 607. The original complex was destroyed by fire in 670, but it was rebuilt before 710. Given the susceptibility of early Japanese structures to fire, it is remarkable that these buildings have survived in such excellent condition. The temple complex includes a central five-story pagoda, a Golden Hall, an inner gate, and much of a wooden corridor that encircles the central area.

Some historians have raised questions about whether the fire that destroyed the original structure actually occurred. If it didn't, the temple complex could be even older

Today, the Horyu-ji Temple remains active in its original role, housing invaluable treasures from the Asuka and Nara periods of Japan's history. The temple is even mentioned in the renowned Japanese classic The Tale of Genji.

7. The Oldest Representation of the Human Form

The Venus of Hohle Fels holds the title of the oldest known figurine representing the human form. Aside from the possibly disputed Zoomorphic Lion Man sculpture, it is the earliest confirmed example of figurative prehistoric art ever discovered (although the Lion Man depicts a figure that is either non-human or half-human).

This 40,000-year-old figurine stands at around 6 centimeters (2.4 inches) in height and is meticulously carved from mammoth ivory. As with most Venus figurines, it portrays a curvaceous woman with exaggerated breasts, hips, and a massive, protruding vulva. Notably, the figure lacks a head, but it features a carved ring above its left shoulder, with signs of wear suggesting it may have been worn as a necklace.

The considerable number of these figurines and the evident care taken in their creation indicate their significant importance to early humans. While many scholars believe they functioned as fertility totems, the exact meaning remains largely speculative.

The Venus was unearthed at the Hohle Fels caves in the Swabian Jura region, near Ulm in southwest Germany. This site, also home to the world's oldest known musical instruments before 2012, revealed the figurine in six pieces about 3 meters (9 feet) below the cave floor, surrounded by animal remains, worked bone, ivory, and flint-knapping debris.

The Hohle Fels caves provide abundant evidence of long-term prehistoric human habitation and have yielded numerous important finds, including the Lion Man figure. Initially dated to 30,000–31,000 years ago, recent refined carbon-dating of bones found near the sculpture now places the Lion Man at 40,000 years old. This piece is significant as it represents an imaginary figure, offering early evidence that humans had developed complex pre-frontal cortexes.

6. The Oldest Musical Instruments

In 2012, researchers uncovered the world's oldest known musical instruments, dating back 42,000–43,000 years. The discovery was made by Professor Nick Conard of Tuebingen University, who also led the excavation of the previous record-breaking find, which was discovered nearby in 2009.

These instruments are bone flutes, one carved from mammoth ivory and the other from a bird’s bone. They were unearthed in the Geissenkloesterle Cave, located in the Upper Danube region of southern Germany. Based on findings from this cave and others in the area, it is believed that humans arrived in the region 39,000–40,000 years ago, just before a harsh climatic period ensued.

Professor Conard suggests that the artifacts found in the region point to the area being a route for the exchange of technological innovations into Europe during that time. Music may have served as a form of entertainment or spiritual practice and could have played a role in behaviors that helped early humans surpass Neanderthals.

Some researchers argue that the origins of musical ability stretch even further back in history. Professor Chris Stringer, a human origins expert at the Natural History Museum in London, who was involved in the discovery of instruments in the Hohle Fels cavern in southwest Germany, proposes that humans may have displayed advanced cultural creativity as early as 50,000 years ago or possibly even earlier in Africa.

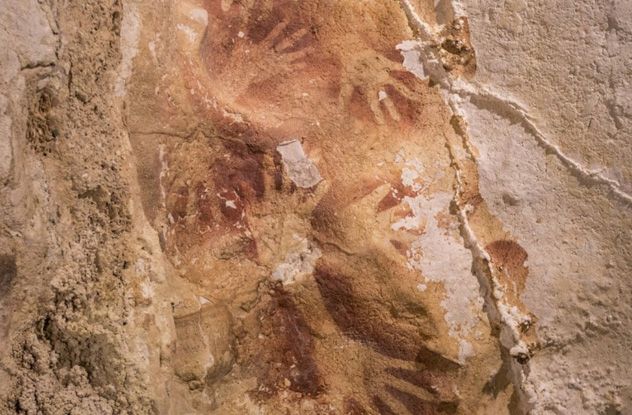

5. The Oldest Cave Paintings

Up until 2014, the oldest known cave paintings were those of Upper Paleolithic animals, which were between 30,000 and 32,000 years old, discovered in the Chauvet Cave located in the Ardeche River valley in France. This discovery led to the widely accepted belief that symbolic artistic thinking began to emerge in Europe around this period.

However, a groundbreaking discovery on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi, east of Borneo, challenges this assumption. In September 2014, scientists confirmed that some of the cave paintings there are over 40,000 years old. These include stenciled handprints (similar to those found globally) and paintings of local wildlife. Notably, one painting of a babirusa, a local animal, was identified as being at least 35,400 years old, making it the oldest known example of figurative art.

Art likely developed independently in various regions across the world. Evidence suggests that Europe was not the sole birthplace of artistic expression. Red ochre dye, commonly used in cave paintings, has been found in Israel, dating back 100,000 years. Additionally, paint-making containers discovered in Africa date back to as much as 100,000 years ago, and these are also considered the oldest known containers.

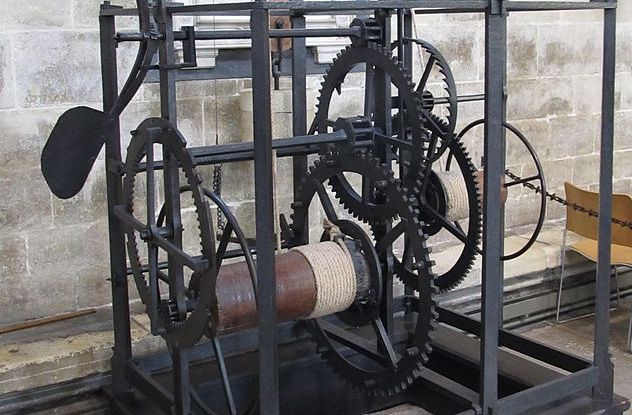

4. The Oldest Working Mechanical Clock

The oldest functioning mechanical clock in existence is housed at Salisbury Cathedral in southern England. Commissioned by Bishop Erghum in 1386, this clock features a system of gears and wheels that operate a bell via ropes, chiming every hour. Its timing mechanism, known as a 'verge and foliot,' governs the clock’s function.

The term 'clock' originates from the German word 'glocke,' meaning 'bell.' Early clocks operated with bells in this manner. Before these mechanical timepieces, clocks were mostly used by astronomers, with sundials and water clocks being the most common timekeeping devices in daily life. While European astronomers divided the day into 24 hours, most communities used 12 irregular hours that fluctuated with the seasons. The introduction of mechanical clocks marked the shift toward more precise timekeeping.

A slightly older mechanical clock, commissioned in Milan, Italy around 1335, no longer functions but remains a notable piece of history.

3. The Oldest Tools

The oldest known tools were discovered in Gona, Ethiopia, and are estimated to be between 2.5 and 2.6 million years old. These tools are not only the oldest ever found, but they also represent the earliest human-made artifacts discovered to date.

These tools, known as Oldowan, are named after the Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania, where similar tools have been found. They are simple, sharp-edged rock fragments that were struck from larger cores and were primarily used for chopping and scraping meat from animal bones.

Approximately 2,600 of these tools have been recovered from the excavation site, though no human remains have been found, leaving the identity of the toolmakers uncertain. It is clear, however, that they predate the earliest known remains of the Homo genus in the region. Similar tools, dating back to around 2.3 to 2.4 million years ago, have also been discovered in other parts of Africa.

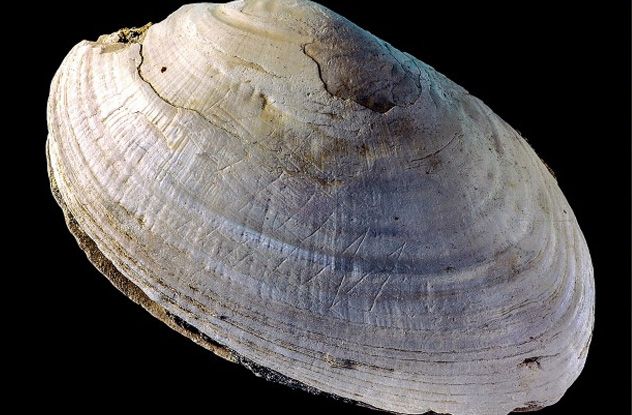

2. The Oldest Example Of Abstract Design

In 2007, archaeologists examining mollusk shells from the island of Java in Indonesia uncovered one with markings on its surface. Other shells showed characteristic perforations near the seams, suggesting that tools had been used on them.

By 2014, researchers confirmed that the shell was likely a tool. The etchings were made by humans, possibly Homo erectus, a species previously believed to be limited to using only stone tools. More remarkably, the zigzag patterns in the etchings provided the earliest known evidence of abstract representation by hominids.

The research team, led by Josephine Joordens from Leiden University in the Netherlands, dated the shell to around 500,000 years old. They demonstrated that the etchings were deliberate, not accidental, by using a microscope to reveal sharp turns at the corners, indicating purposeful carving. The holes in many of the shells were found to have been made with shark’s teeth, also discovered at the site. The signs of weathering on the etchings ruled out the possibility of a hoax or recent markings by the researchers.

Still, it's premature to declare the evidence definitive. It remains uncertain whether Homo erectus had a significant presence on the island, and the carvings may instead be the work of Homo sapiens. Until more examples are discovered, no conclusive judgment can be made. However, even if the carvings aren't intentionally symbolic, they represent the oldest doodles ever found.

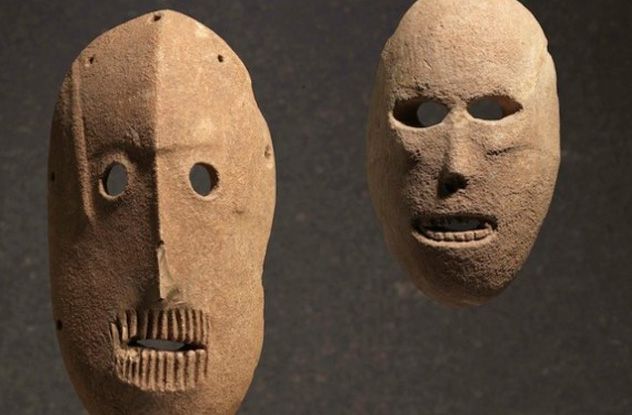

1. The Oldest Masks

The oldest masks ever discovered are a set of 9,000-year-old stone masks, originating from what is now Israel during the Neolithic period. These masks were recovered from various locations in the Judean Desert and the Judean hills, and are currently housed in the Israel Museum in Jerusalem.

The masks feature stylized facial representations, some of which may depict skulls. They have holes around their edges, likely designed for wearing. These holes might have been used to thread hair through for a realistic effect or to attach cords for hanging them from pillars or altars. While it's unclear whether they were worn or used for rituals, researchers note that their carved features seem crafted with human comfort in mind, such as eyes designed to offer a broad field of vision.

Ancient cave paintings often show individuals wearing masks. Archaeologists speculate that many of these masks were crafted from biodegradable materials, which means they have disappeared forever, making the few surviving examples even more precious.