Throughout history, humanity has faced numerous epidemics and plagues, yet some are particularly remembered for their devastating effects and profound influence on future societies. Here, we explore the most severe plagues documented in human history.

RELATED: 10 Of The Most Horrific Plagues in Human History

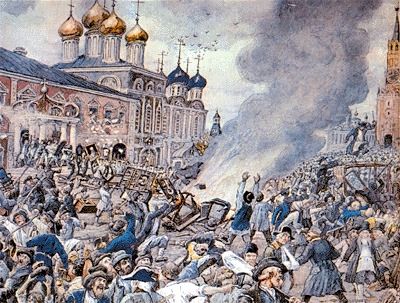

10 The Moscow Plague and Riots 1771

The initial indications of the plague in Moscow emerged in late 1770, escalating into a full-blown epidemic by spring 1771. Authorities implemented drastic measures, including mandatory quarantines, uncompensated destruction of infected properties, and the closure of public baths, sparking widespread fear and resentment among residents. The city's economy ground to a halt as factories, markets, shops, and government offices shut down. Severe food shortages ensued, drastically worsening living conditions for most Muscovites. Wealthy nobles and affluent citizens fled the city to escape the outbreak. On September 17, 1771, approximately 1,000 protesters gathered at the Spasskiye gates, demanding the release of detained rebels and an end to quarantines. The army dispersed the crowd and quelled the uprising, with around 300 individuals facing trial. A government commission led by Grigory Orlov arrived on September 26 to restore stability, implementing plague containment measures and providing employment and food to pacify the people of Moscow.

9 The Great Plague of Marseille 1720 – 1722

The Great Plague of Marseille marked one of Europe's most severe bubonic plague outbreaks in the early 18th century. Striking Marseille, France, in 1720, the disease claimed 100,000 lives in the city and nearby regions. Despite the devastation, Marseille rebounded swiftly, with economic activity recovering within a few years as trade expanded to the West Indies and Latin America. By 1765, the population had returned to pre-1720 levels. This epidemic was distinct from the Black Death, the catastrophic bubonic plague outbreaks of the 14th century. Efforts to curb the plague included an Act of Parliament in Aix imposing the death penalty for communication between Marseille and the rest of Provence. A plague wall, the Mur de la Peste, was constructed across the countryside to enforce this isolation (pictured above).

8 The Antonine Plague 165 – 180 AD

The Antonine Plague, also referred to as the Plague of Galen after the physician who documented it, was an ancient pandemic believed to be either smallpox or measles. It was introduced to the Roman Empire by soldiers returning from military campaigns in the Near East. The outbreak claimed the lives of two Roman emperors—Lucius Verus, who died in 169, and Marcus Aurelius Antoninus, his co-regent, whose family name, Antoninus, became associated with the epidemic. The disease resurfaced nine years later, as recorded by Roman historian Dio Cassius, causing up to 2,000 deaths daily in Rome, affecting a quarter of those infected. Estimated total deaths reached five million, with some regions losing up to one-third of their population. The plague severely weakened the Roman army and had profound social and political impacts across the empire, influencing literature and art. (Depicted above is a plague pit containing remains of victims from the Antonine Plague.)

7 The Plague of Athens 430–427 BC

The Plague of Athens was a catastrophic epidemic that struck the city-state of Athens during the second year of the Peloponnesian War (430 BC), when victory still seemed possible. It is thought to have entered Athens via Piraeus, the city's port and primary source of food and supplies. The disease also affected Sparta and much of the eastern Mediterranean. The plague recurred in 429 BC and again in the winter of 427/6 BC. While modern historians debate its role in Athens' defeat, many agree that the war's outcome may have facilitated the rise of the Macedonians and, eventually, the Romans. Traditionally identified as an outbreak of bubonic plague, re-examinations of symptoms and epidemiology have led scholars to propose alternative theories, including typhus, smallpox, measles, and toxic shock syndrome.

6 The Great Plague of Milan 1629–1631

The Italian Plague of 1629-1631, also known as the Great Plague of Milan, was a series of bubonic plague outbreaks that ravaged northern Italy. This devastating epidemic resulted in approximately 280,000 deaths, with Lombardy and Venice being among the hardest-hit regions. It marked one of the final chapters of the centuries-long bubonic plague pandemic that began with the Black Death. The plague was introduced to Mantua in 1629 by French and German troops during the Thirty Years’ War (1618–1648). Infected Venetian soldiers retreated into northern and central Italy, further spreading the disease. Milan alone lost around 60,000 people, nearly half of its 130,000 inhabitants.

RELATED:10 Bizarre Facts About The Dancing Plagues

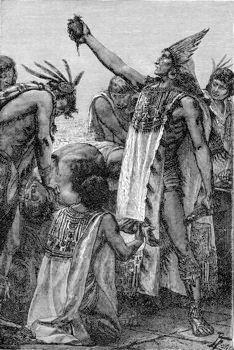

5 The American Plagues 16th Century

Prior to the arrival of Europeans, the Americas remained largely cut off from the Eurasian-African landmass. The initial widespread interactions between Europeans and the indigenous populations of the Americas introduced devastating epidemics of measles, smallpox, and other Eurasian diseases. These illnesses spread quickly among native communities, often preceding direct contact with Europeans, resulting in a sharp population decline and the collapse of indigenous cultures. In the 16th century, smallpox and other diseases severely weakened the Aztec and Inca civilizations in Central and South America. The loss of population and the deaths of key military and social figures played a significant role in the fall of these empires and the subsequent European domination. However, diseases traveled in both directions; syphilis, for instance, was brought back to Europe from the Americas, causing widespread devastation.

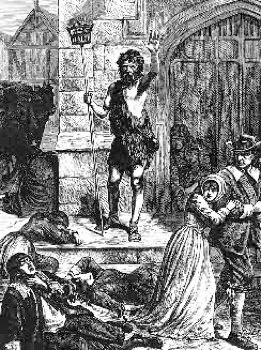

4 Great Plague of London 1665 – 1666

The Great Plague (1665-1666) was a catastrophic disease outbreak in England, claiming the lives of 75,000 to 100,000 people, roughly a fifth of London's population. Historically attributed to bubonic plague, caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis and spread by fleas, this epidemic was far less severe than the earlier Black Death pandemic that ravaged Europe from 1347 to 1353. The 1665-1666 outbreak is remembered as the 'great' plague because it marked one of the last major occurrences in England. While the disease has traditionally been identified as bubonic plague, no direct evidence of the plague bacterium has been found. Some contemporary researchers argue that the symptoms and incubation period suggest the cause may have been a viral hemorrhagic fever-like illness. (Pictured above is a mortality list from the plague era.)

3. The Black Death 1347 – 1351

The Black Death (also referred to as The Black Plague or Bubonic Plague) stands as one of the most devastating pandemics in human history. Traditionally believed to be caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis, recent studies suggest alternative diseases might have been responsible. The origins of the plague remain a topic of debate among scholars. Some argue it began in China or Central Asia in the late 1320s or 1330s, spreading via trade routes and reaching Crimea in southern Russia by 1346. Others contend it was already endemic in southern Russia. Regardless, the plague rapidly spread to Western Europe and North Africa in the 1340s. Global fatalities are estimated at 75 million, with 25 to 50 million deaths occurring in Europe. The plague recurred periodically with varying intensity until the 1700s, causing over 100 epidemics across Europe.

(This article is licensed under the GFDL because it contains quotations from Wikipedia.)

SEE ALSO: 8 Fascinating Facts About Plague Doctors

2 The Third Pandemic 1855 – 1950s

The “Third Pandemic” refers to a significant outbreak of plague that originated in China’s Yunnan province (pictured above) in 1855. This wave of bubonic plague reached every inhabited continent, claiming over 12 million lives in India and China alone. The World Health Organization marked the pandemic as active until 1959, when global deaths decreased to 200 annually. The plague was endemic among infected ground rodents in central Asia, where it had been a persistent threat to human populations for centuries. However, increased movement due to political conflicts and global trade facilitated its worldwide spread. Recent studies indicate that the Black Death may still lie dormant.

1. Plague of Justinian 541 – 542

The Plague of Justinian was a devastating pandemic that struck the Byzantine Empire, including its capital Constantinople, between 541 and 542 AD. Most historians attribute the outbreak to bubonic plague, which later gained notoriety for its role in the Black Death of the 14th century. Its societal and cultural effects were comparable to those of the Black Death. According to 6th-century Western historians, the plague reached central and south Asia, North Africa, Arabia, and Europe, extending as far north as Denmark and as far west as Ireland. The disease recurred in the Mediterranean region with each generation until around 750, significantly influencing the course of European history. Named after Emperor Justinian I, who ruled during the outbreak and contracted the disease, the plague is believed to have killed up to 5,000 people daily in Constantinople at its peak. It wiped out approximately 40 percent of the city’s population and up to a quarter of the eastern Mediterranean’s human inhabitants.