There's something captivating about spotting an island on the horizon. These secluded pieces of land, surrounded on all sides by endless ocean, exude a sense of mystery, offering a new realm to discover.

Equally captivating is the story of the islanders, whose deep connection with their environment has evolved over centuries. Their cultures and histories are intricately tied to the harsh landscape and their relative isolation from the outside world.

Just as the first settlers were driven to build a life on the edges of the known world, these Atlantic islands continue to spark the curiosity of explorers, adventurers, and anyone drawn to remote and enigmatic destinations.

10. Rockall

Although it's more of a guano-covered granite rock standing 18 meters (60 ft) tall in the open ocean than an actual island, Rockall is officially considered the westernmost point of the UK. Positioned 465 kilometers (290 mi) off Britain's coastline and 710 kilometers (440 mi) south of Iceland, it’s as close as one can get to being in the “middle of nowhere.”

Despite its isolated location, Norse sailors were aware of the rock, calling it “Rocal,” likely meaning “windy bald head.” The name perfectly suits this barren rock. As British politician Lord Kennet put it, “There can be no place more desolate, despairing, and awful.”

Rockall is occasionally called “Rocabarraigh” in Scottish Gaelic. According to Scottish legend, Rocabarraigh is an island or rock that will emerge three times, with the final appearance marking the end of the world.

In 1955, during a time when the threat of nuclear war was imminent, the British Admiralty formally claimed Rockall on behalf of the Crown. This act ensured the islet would not be used as a Soviet observation post when the UK tested its first nuclear missile in the North Atlantic.

9. Jan Mayen

Jan Mayen is a substantial island located roughly halfway between Norway and Greenland, about 595 kilometers (370 mi) north of Iceland. The island is made up of two sections, a smaller southern part and a much larger northern section, connected by an isthmus.

Jan Mayen is a volcanic island, with its landscape dominated by the towering Beerenberg volcano. It's believed that the island was first discovered by Norse sailors, who described an island two days' sail north of Iceland.

They called it “Svalbaro” (“cold coast”). However, as the Viking Age came to an end, Norwegians and Icelanders ceased most long-distance voyages, and the island faded from memory for many centuries.

Jan Mayen has a complex history of discovery. It was officially rediscovered by three separate expeditions in the summer of 1614. This is when the island was finally named after Jan, a Dutch captain of a whaling ship who reached the island in May.

Afterward, Jan Mayen became a refuge for Dutch whalers who set up semi-permanent hunting stations there. Thousands of whales were hunted in the waters around Jan Mayen, with some species almost driven to local extinction.

In 1634, seven Dutch whalers became the first to attempt overwintering on the island. Tragically, all perished from scurvy and illnesses caused by consuming raw polar bear meat. A few years later, the whales seemingly abandoned Jan Mayen for safer waters, prompting the Dutch to completely abandon the island. It remained quiet once more.

In the 20th century, the island became part of the Kingdom of Norway. Today, it is accessible only to a select few, primarily scientists or Norwegian military personnel.

8. Litla Dimun

Litla Dimun is the smallest of the 18 main islands of the Faroe Islands. It has a cylindrical cone shape, with its entire southern side made up of steep cliffs, making it notoriously difficult to land on the island.

This challenging landing is likely the reason why the island is believed to have never been inhabited by humans, a unique feature among Atlantic islands. However, it has been used for sheep grazing since the Neolithic era.

Up until the 19th century, Litla Dimun was home to feral sheep, descendants of the sheep brought to the Faroes by the first settlers from Northern Europe. The breed was similar to those found on other isolated North Atlantic islands off the coast of Scotland. Today, the feral sheep are extinct, and the island now hosts modern Faroese sheep.

In autumn, Faroese farmers travel to Litla Dimun to gather the sheep for slaughter and shearing. The sheep are herded into a pen on the island's northern side, where their feet are tied together.

The sheep are then lowered in nets over the cliffs into a boat, which transports them to the mainland, ensuring the animals are kept indoors throughout the winter months.

7. Foula

Foula, part of the Shetland Islands, is one of the most isolated inhabited places in Europe. With a population of just 38, the island's history stretches back as far as 3000 BC.

On the northern side of Foula, archaeologists have studied a subcircular stone circle, confirming that it was built before 1000 BC. The stone formation is slightly elliptical, and its alignment with the winter solstice suggests it may have been used for religious rituals.

Foula has preserved a unique culture steeped in Norse traditions. The island's name, much like many other Scottish islands, originates from the Norsemen who conquered and settled there during the Viking Age.

The islanders still follow the Julian calendar, marking Christmas on January 6. As one local resident described, “Families open their presents in their own homes, and then in the evening, we all tend to end up in one house.”

Foula was among the last places where the now-extinct Norn language was spoken daily. Norn, a language derived from Old Norse, was common across the Northern Isles until the late 18th century. Its decline began when the Northern Isles were transferred to Scotland by the Norwegian Crown in the late 15th century.

6. St. Kilda

St. Kilda is a remote archipelago situated far off the west coast of Scotland. Hirta, the largest island in the group, is the only one that remains inhabited. The islands are among the most famous of Scotland's isolated regions, known for their isolation, fascinating history, and breathtaking landscapes.

The islands present a dramatic sight, with towering cliffs rising steeply from the sea, often hundreds of feet high. Hirta can only be reached through a few difficult entry points, and even those are accessible only during the best weather conditions.

Inhabited for over 2,000 years, there is evidence of even earlier Stone Age settlements. Icelandic records suggest that Norsemen arrived and assimilated into the island culture during the Viking Age. This is further supported by the presence of many Norse place names on the islands.

The defining theme of St. Kilda's history is the intense isolation endured by its inhabitants. So cut off were the islands that the people retained a unique religion blending druidism with Christianity. Druidic altars, still present in the 18th century, stood as a reminder of the islanders' resistance to the pressures of religious conversion.

The islanders’ indifference to the outside world was exemplified when soldiers arrived in search of Prince Charles Edward Stuart, a claimant to the British throne. It was revealed that the islanders had no knowledge of him, nor had they ever heard of their own monarch, George II.

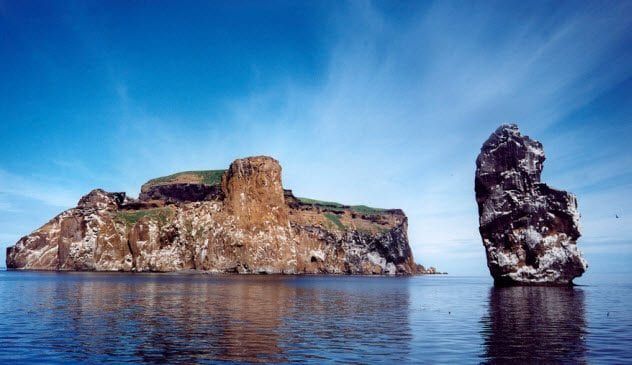

5. Drangey

Drangey is an island situated in the heart of Skagafjorour, a vast fjord in northern Iceland. This island is a remnant of a 700,000-year-old volcano that has since eroded, leaving behind a natural fortress surrounded by steep cliffs. It can only be accessed via a single route.

During the 11th century, the Icelandic legend of Grettir the Strong tells of his exile to Drangey, where he lived for several years with his brother and a slave. Exile was one of the harshest punishments in Viking Age Iceland.

According to the tale, the last fire on Drangey was extinguished, and the men were left without a means to light another. With no boat available on the island, Grettir swam over 6 kilometers (4 miles) of open ocean to the mainland at Reykir to bring back fire. He eventually succumbed to death from an infection after being killed by his enemies.

Drangey is a sanctuary for millions of seabirds. Each summer, as many as 200 farmers from surrounding areas would hunt the birds, with a successful season yielding around 200,000 birds.

The birds were typically hunted using three rafts lashed together with rope, equipped with nooses made from horsehair. This technique, once common in Iceland, is now regarded as cruel, as the rafts would sometimes drift away, leaving birds to perish in the nooses from starvation over several days.

4. Surtsey

Located just off Iceland's southern coast, Surtsey is the youngest island in the Vestmannaeyjar archipelago. The island emerged from the sea on November 14, 1963, following an underwater volcanic eruption.

The eruption lasted four years, creating the 2.6-square-kilometer (1 square mile) island. Since then, erosion has significantly reduced its size, shrinking it to nearly half its original area. The island has become a subject of immense interest for scientists, particularly geologists and biologists. As a result, access is restricted to scientific researchers only.

Though other islands have briefly formed off Iceland’s coast, they were usually sandbanks built of coarse volcanic gravel created when molten lava meets cold seawater and erupts violently. The eruption of Surtsey was unique because it reached a stage where seawater no longer flowed into the vents, allowing the lava to flow uninterrupted.

Before the eruption ceased, plant life had already begun to take root on Surtsey. Today, the island is largely covered in moss. Birds soon arrived and began to settle, and by 1998, the first bush was spotted growing on the island.

In 1977, scientists were baffled when they discovered a potato plant growing on Surtsey. However, it was soon revealed that the plant had been a prank, planted by teenagers from a nearby island.

Later on, a scientist, while relieving himself outdoors, left behind a piece of human waste, from which a tomato plant unexpectedly grew. Both the potatoes and tomatoes were removed, and the pranksters were reprimanded for introducing non-native species to the island.

3. Rona

Rona, also known as North Rona to differentiate it from another Scottish island with the same name, lies far to the north of Scotland. Its isolation is so extreme that it's often left off UK maps. Over the past 1,500 years, it has been inhabited and deserted a few times, with the population being very small, numbering only about 30 people.

Before the Viking Age, Christian hermits likely inhabited the island. Many Scottish islands were later conquered by the Vikings and came under Norwegian rule for several centuries. While no direct evidence of Norse settlement has been found on Rona, the island’s name may be of Norse origin.

In the eighth century, Saint Ronan is said to have made Rona his home. He is believed to have built the small Christian oratory still standing on the island today. This oratory may be the oldest surviving Christian structure in Scotland.

Visitors to the island can crawl into the small, sunken oratory, built from earth and unmortared stones, where a rough stone cross stands in the corner. This glimpse into the past offers a small insight into the lives of the hermits who lived in voluntary isolation on Rona a thousand years ago.

2. Flannan Isles

The Flannan Isles, a cluster of seven small islands off Scotland’s coast, cover just 145.5 acres in total. These islands have been uninhabited since the lighthouse on the largest island, Eilean Mor, was automated.

The Flannan Isles are remote, yet they are closer to the Outer Hebrides than Hirta, which has been continuously inhabited for thousands of years.

The Flannan Isles' small size and isolation likely contributed to their long periods of abandonment. However, remnants of a chapel, several bothies (huts), and other signs point to the islands once being the retreat of a secluded monastic community.

In the late 1800s, a lighthouse was constructed on Eilean Mor. The islands became the site of a famous mystery in 1900, when all three lighthouse keepers vanished without a trace.

The men disappeared during a violent storm that wrecked one of the two landings on the island, severely damaging equipment and infrastructure. At one site, turf was torn away from a 61-meter (200 ft) cliff, indicating that massive waves had struck the island.

The mysterious disappearance captured the attention of the media and fascinated the British public. Numerous wild theories emerged, especially since everything in the lighthouse appeared in order, except for a chair that had been tipped over at the kitchen table.

The Northern Lighthouse Board’s regulations required the lighthouse to never be left unattended, yet all three men vanished at once. An unusual detail was the oilskins left behind, indicating that one of the keepers had hurried outside without taking the time to put on proper gear.

This enigma remains unresolved. While several plausible theories have been proposed, the disappearance still captures the imaginations of mystery enthusiasts to this day.

1. Svalbard

Svalbard, an archipelago located far beyond the Arctic Circle, holds the title of the northernmost permanent settlement on Earth. While it is an unincorporated territory of Norway, the largest island also hosts a Russian mining settlement.

The relationship between Norway and Svalbard is complex. The region is officially a demilitarized zone, and foreign governments that have signed the Svalbard Treaty are allowed to extract its natural resources. By 2016, there were 45 signatories to the treaty.

Glaciers blanket 60 percent of Svalbard’s land area, and during the winter months, the region experiences a polar night. In Longyearbyen, the largest settlement, this polar night lasts from October 26 until February 15.

There are no comprehensive road networks on the islands, with only limited roads present within towns or mining zones. The primary mode of transport, particularly in winter, is the snowmobile.

Venturing outside the settlements can be risky, as Svalbard is home to a large polar bear population. Anyone traveling beyond the settlements is required to carry deterrents for polar bears, and the government strongly advises carrying a firearm.

Svalbard might seem like a haven for nature lovers and gun enthusiasts. However, moving to the islands is nearly impossible unless one already has a job there. Most homes on the islands are owned by companies and rented to their employees.