Let’s be honest: the English language can be pretty strange. It's disorganized, chaotic, and sometimes the rules simply make no sense. Our grammar and everyday phrases are full of quirks, many of which are completely nonsensical, frustrating those trying to learn English for the first time.

Yet, the most perplexing and confusing element of English has to be idioms. How could it not? By definition, an idiom is a phrase that doesn’t make sense if taken literally—you have to understand its meaning, which rarely, if ever, corresponds to the literal words. For example, how does ‘raining cats and dogs’ translate to ‘it’s pouring rain’? It doesn’t. At least, it doesn’t seem to.

The funny thing about these oddities of language is that we often lack the historical or cultural context that would help us understand them better. That doesn’t mean the sense isn’t there; it just means we are far removed from the time and culture from which the phrase originates. Once we uncover the backstory and add the context, the meaning often becomes clearer. And if it doesn’t make more sense...well, at least it’s probably an interesting tale.

10. Take a Rain Check

The origin of the idiom can be traced to the late 19th century, particularly to baseball in the 1870s. If a game was interrupted by rain, teams would provide new tickets for the postponed match. These tickets came to be called rain checks. By the 1890s, the phrase started to take on a more metaphorical meaning, and now, we use 'take a rain check' in a variety of situations unrelated to the sport itself.

9. Pardon my French

The expression 'Pardon my French' is widely used, even though it doesn’t really make logical sense. It’s typically said after someone swears, followed by a quick apology like 'Oh, pardon my French.' Of course, the words just uttered were not in French at all—just regular English. But where does this strange apology come from? Originally, it was used when someone actually did speak French.

In the 1800s, it was common for the educated classes to sprinkle French phrases into their speech. However, those who were less educated spoke only English and had no understanding of French. This led to the creation of the phrase. The mystery remains as to how we transitioned from apologizing for actual French words to using it as an apology after swearing.

8. Saved by the Bell

Unlike many idioms, there are several theories about the origin of 'saved by the bell.' One popular explanation dates back to the 18th century, a time when there were real concerns about people being mistakenly buried alive. To prevent such a horrific fate, a system was put in place: a string was tied to the finger of the supposedly dead person, with the other end connected to a bell outside the coffin. If the person was still alive and moved, it would ring the bell, alerting a guard. While this is an intriguing story, there's no solid evidence to back it up.

Another theory traces the phrase to boxing. In this context, a bell would ring to signal the end of a round, effectively saving a boxer who might have been about to lose. This version is backed by documented evidence. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the earliest use of 'saved by the bell' in this context appeared in a newspaper article from 1909.

7. Bury the Hatchet

This one has an interesting historical root. The phrase 'bury the hatchet' comes from a Native American peace ritual. When two warring tribes made peace, their chiefs would literally bury their war axes as a symbol of ending hostilities. The practice was first recorded in the late 1600s, though it's likely older, as it was documented by colonists. An Iroquois legend adds that the Five Nations buried their weapons under a tree, marking a new alliance, but the tree grew above an underground river, causing the weapons to be washed away. The phrase, once referring to this ceremony, eventually evolved into a common saying.

6. A Chip on One’s Shoulder

In the 1800s, young American boys seeking a fight would place small chips of wood or bark on their shoulders, daring others to knock them off. If the other boy succeeded, it typically led to a physical confrontation, but if he failed, the one with the chip would be ridiculed. This practice dates back to at least 1830, according to the OED, though it might be older. By the 1850s, the phrase began to take on its modern meaning. Fascinating, right?

5. God Bless You

The phrase 'bless you' has several potential origins, similar to 'saved by the bell.' One theory is that sneezing made you vulnerable to evil spirits, and the blessing was meant to protect you. Another explanation ties the phrase to Pope Gregory I, who encouraged blessing sneezers during the bubonic plague as a form of divine protection. A third version stems from the belief that the heart momentarily stops during a sneeze, and the blessing was either to congratulate survival or ensure it. So, which one is true? We don't really know.

4. Bite the Bullet

While the precise origins of 'bite the bullet' are debated, most agree it comes from an old battlefield practice. During surgeries, patients were given something to bite—often a piece of leather or, yes, a bullet—to ease the pain. Additionally, soldiers would bite a bullet to stay silent during disciplinary whippings, as some regiments took pride in remaining completely quiet. The first recorded use of this idiom is found in Rudyard Kipling's 1891 novel 'The Failed Light.'

3. To Hit the Hay

The phrase 'to hit the hay' is one we often use, even though its connection to going to bed may not seem obvious. Historically, though, it makes more sense. The most likely theory behind this idiom is that it comes from when mattresses were made from hay, straw, or leaves—far from being comfortable. This practice lasted for some time, and even though beds are no longer made with hay, the expression stuck.

One point of contention with this theory is the Oxford English Dictionary's first recorded instance of 'hit the hay' in 1912. By this time, mattresses were no longer made from straw. But this doesn’t completely disprove the theory. It’s worth noting that back then, new phrases often had apostrophes around them to indicate they weren’t meant literally, and the absence of apostrophes in the 1912 citation might hint at a longer usage of the phrase.

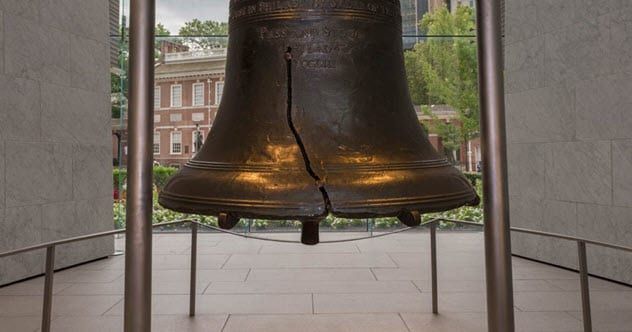

2. Dead Ringer

Similar to 'saved by the bell,' the expression 'dead ringer' is frequently linked to an old tale involving the fear of being buried alive in the 19th century. It refers to the bell outside a coffin that was tied to the finger of the presumed dead person. The 'dead ringer' was the person thought to be dead—or so the story goes. But there’s little evidence to support this version of the idiom's origin. Plus, this story doesn’t explain how 'dead ringer' came to mean something that’s an exact replica of something else.

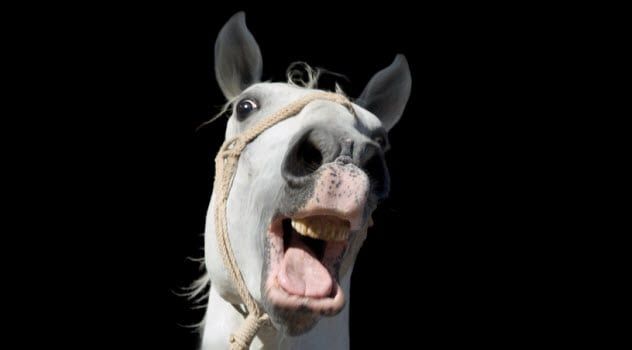

The origins of the term 'dead ringer' are widely believed to come from the world of horse racing. The word 'ringer' was once slang for a criminal practice where one horse would be substituted for another in a race, usually a lookalike. This tactic was advantageous because it could manipulate betting odds to the advantage of those in the know. But what does 'dead' add to the phrase? The term 'dead' in this case doesn’t refer to actual death but to precision, as in 'dead shot.' Thus, a 'dead ringer' refers to an exact substitute, and the term has expanded beyond the racing world.

1. Hill to Die On

This phrase has its origins in military strategy. Holding the high ground, or a hill, offers a significant tactical advantage. It provides better visibility and, importantly, makes any attempt to take the position much harder because attackers must charge uphill—a much more physically demanding task than advancing across a flat field.

Fighting uphill against an opponent who has the high ground isn’t exactly an ideal situation either. The phrase refers to this dilemma—whether the struggle is worth the cost. Some have speculated that this saying became widely used during the Vietnam War, where numerous battles over seemingly insignificant hills led to heavy casualties, only for the positions to be abandoned later. However, there isn’t enough evidence to support this theory definitively.