Fungi are truly outliers in the natural world. While they share a closer genetic bond with animals rather than plants, they were long categorized as plants. Their cell composition is distinct, and their way of life is equally unusual. They inhabit a realm entirely of their own.

Evolution has shaped them into strange, often unsettling forms. Below are 10 of the most bizarre, unsettling fungi you’d rather not stumble upon if you venture into the woods.

10. Dead Man’s Fingers

A large number of fungi remain hidden beneath the soil throughout most of the year. You only encounter them when their spore-producing structures emerge. Mushrooms are simply the reproductive organs of fungi, serving to disperse their spores. However, not all fungi produce mushrooms.

Xylaria polymorpha, also known as dead man’s fingers, produces twisted, black branches. The name is fitting, as these eerie structures resemble the fingers of a deceased person attempting to claw their way out of the earth. The dark surface of these branches is the spore-bearing part of the fungus, which feeds on decaying plant matter beneath the soil.

9. Devil’s Tooth

Hydnellum peckii is known by various names: bleeding-tooth fungus, strawberries and cream, red-juice tooth, and Devil’s tooth. All of these reflect the striking appearance of this fungus. A bright red fluid oozes from the top of its cap.

This fungus forms a mutualistic relationship with pine trees by attaching to their roots, assisting them in absorbing nutrients from the soil. This is a common tactic, as many plants and fungi engage in symbiotic partnerships. The fungus’s fine filaments are able to infiltrate the soil more effectively than the plant roots. In return, the plants supply sugars to the fungi, and the fungi provide vital minerals.

The exact reason behind the fungus’s production of the blood-like substance remains unknown. Studies of the fluid have revealed that it contains atromentin, a chemical known for its anticoagulant properties. Therefore, the bleeding-tooth fungus might have the potential to cause bleeding.

8. Common Stinkhorn

Phallus impudicus is a Latin term translating to 'shameless penis.' One glance at the structure that emerges from an underground ‘egg’ makes the reason for its name immediately clear. The common stinkhorn can grow as much as 25 centimeters (10 inches) in just a few hours—truly shameless.

The name 'stinkhorn' is equally fitting. The 'horn' indeed emits a foul odor. The tip of the fruiting body is coated in a slimy, smelly substance. This stench draws flies, which crawl over the end of the structure, inadvertently carrying spores with them.

Etty Darwin, the granddaughter of Charles Darwin, was so horrified and disgusted by the stinkhorn's shape that she would rise before dawn to chop down any she encountered.

7. Ink Cap

The common ink cap starts off as a rather plain mushroom. Its cap is a dull, creamy-brown that gradually darkens. As the mushroom matures, it appears to melt and begins to drip onto the ground. This process of deliquescence is what gives the ink cap its name, as it looks as though it is leaking ink.

The common ink cap (also known as Coprinopsis atramentaria) has another sinister feature. It’s also referred to as tippler’s bane. Despite its unappealing appearance, the mushroom has a mild taste and is completely edible.

The real danger of this mushroom arises when it’s consumed with alcohol. The fungus produces a substance called coprine, which can be fatal if combined with alcohol, even if alcohol is consumed days after eating the mushroom.

6. Octopus Stinkhorn

Clathrus archeri is known by two common names: octopus stinkhorn and Devil’s fingers. No matter what you call it, its appearance is certainly one of a kind. Like other stinkhorn species, it emerges from an egg-like structure just below or on the surface.

This stinkhorn emits a nauseating odor to draw in the flies necessary for spreading its spores. Upon hatching, it develops 4–8 'fingers'.

While some stinkhorn fungi are edible, the gelatinous fungal eggs, though not the most appetizing to many, are considered a delicacy in certain cultures. However, the Devil’s fingers are not recognized as a culinary treat in any known cuisine.

5. Cedar-Apple Rust

Cedar-apple rust is a fungus with a complicated life cycle, none of it particularly pleasant. This fungus thrives on both apples and juniper trees, but cannot fully survive on just one of them.

In May, spores land on the leaves of apple trees, causing unsightly spots to appear on the undersides. These spots release spores into the air, which then drift until they settle on a juniper tree.

Upon landing on the juniper, the fungus induces the tree to grow round, tumor-like galls. These galls are the 'cedar apples' that lend the fungus its name. From these galls, yellow spikes emerge. When the first warm rain hits these spikes, spores are released to infect apple trees and continue the cycle.

4. Cordyceps

Cordyceps fungi are highly valued in many alternative medicines. In China, they are used in soups. While mushroom soups are common globally, the unique aspect of Cordyceps is that they grow from the bodies of insects and arachnids.

A single spore landing on an insect is often enough to infect it. The fungus grows quickly within the insect’s body, consuming its internal organs as food. Once the insect is fully drained, the fungus needs to break free in order to release its spores. It does this by sending long, spore-producing spikes through any available opening.

Some Cordyceps are especially devious. After infecting an ant, the fungus releases chemicals that compel the ant to climb high into trees and cling to them with its mandibles. From this elevated position, the fungus can more effectively disperse spores to infect other ants.

3. Anemone Stinkhorn

The anemone stinkhorn (also known as Aseroe rubra) is another member of the stinkhorn family and has ties to the infamous wildlife of Australia. It was the first fungus native to Australia to be scientifically described.

The scientific name refers to the sticky, smelly gleba characteristic of stinkhorns, which is used to lure flies. Aseroe comes from the Greek word meaning 'disgusting juice.' The gleba, which is an olive-brown, gelatinous substance, is packed with spores. Immature specimens are entirely coated in gleba, which gradually comes off as flies walk over it, carrying the spores on their bodies and feet.

After emerging from its 'egg,' the fungus grows 6–10 split arms or tentacles, giving it a striking resemblance to an anemone.

2. Brain Fungus

While Cordyceps fungi do invade the brains of insects, they do not resemble brains. However, Gyromitra esculenta does.

Morel mushrooms are a favorite among chefs and food lovers for their exquisite flavor. The edible varieties share a distinct honeycomb appearance. However, the world of mycology also contains fungi that look similar to edible species but should be avoided. Many types related to morels are known as 'false morels' due to their potential toxicity, which can trick the unwary into eating them.

Gyromitra esculenta may appear off-putting—and it's poisonous when raw—but it is consumed in parts of Scandinavia. Even when cooked, it has been associated with fatalities. Regular consumption of Gyromitra esculenta can result in toxic accumulation in the body.

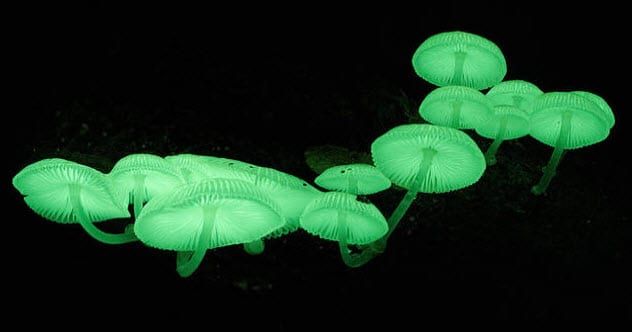

1. Luminous Mushrooms

Numerous fungi are bioluminescent, emitting light, but the exact reason behind this phenomenon remains uncertain. The most widely accepted theory is that the light serves to attract insects, similar to how stinkhorns use their foul scent. Just as insects are drawn to porch lights, they are attracted to these glowing mushrooms, helping in the dispersal of spores.

The phenomenon of bioluminescent fungi has been observed for centuries. The ghostly green glow emitted from decaying wood, a result of fungi feeding on it, has been referred to as fox fire and faerie fire. This glow is triggered by an enzyme known as luciferase. With our current understanding of the process, there are ideas that genetic engineering could one day be used to create trees that glow in the dark, illuminating pathways.