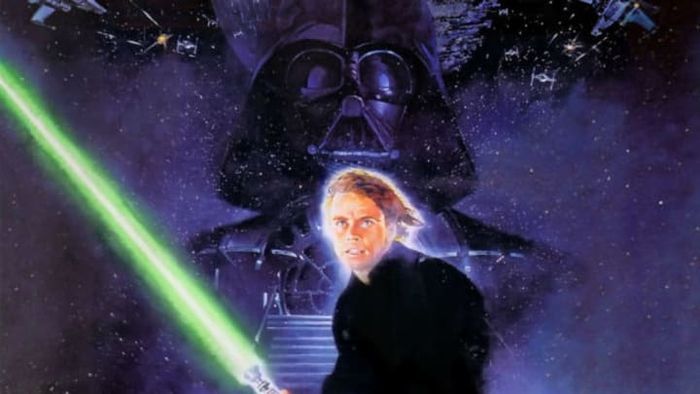

Larry Dewayne Riddick, Jr. couldn't have foreseen a future where pirating blockbuster films would be as simple as a mouse click. In just a few short years, stealing movies for profit or rebellion would become a digital endeavor.

But in 1983, Riddick had no such luxury. If he wanted a copy of Return of the Jedi to sell illegally, he had to resort to more primitive and dangerous tactics—using force to get what he wanted.

At 18, Riddick waited in the parking lot of the Glenwood Theaters in Overland Park, Kansas, as projectionist John J. Smith left the building. Jedi was in its sixth week as the nation's top film. After midnight, Riddick approached Smith, brandished a gun, and demanded the movie reels.

Smith informed him that around 20 people remained in the theater. Riddick waited impatiently in Smith’s car for 20 minutes until the final moviegoer exited. Once inside, he compelled Smith to transfer the 70mm film from large metal canisters into smaller, portable containers—a process that lasted over an hour.

After preparing the film for transport, Riddick made his escape. In the dangerous realm of movie piracy, he had stolen a treasure of immense value. Return of the Jedi, the epic finale of the original Star Wars trilogy, was so highly sought after that a wealthy couple later agreed to pay $10,000 for the stolen print.

iStock

Unauthorized screenings of films have been a problem since the dawn of cinema. Early trade publications featured ads cautioning against copyright violations by “dupers.” When the original Star Wars debuted in 1977, illegal copies were traded for up to $1000.

The 1980s introduced a game-changer: videocassette players. Pirates could now replicate films endlessly, selling them at high prices to eager buyers. Wealthy individuals or international clients, frustrated by delayed foreign releases, became prime targets. Often, projectionists could be persuaded with a few hundred dollars to temporarily “lend” the film for duplication, a practice that harmed only studios and theaters.

When Return of the Jedi premiered in May 1983, over 30 million households worldwide had VCRs, a number poised to skyrocket in the coming years. This created a fertile ground for bootlegging, with the third (and presumed final) installment of the Star Wars series being the most enticing target.

20th Century Fox, the distributor of Return of the Jedi, anticipated the film would attract piracy. To deter illegal copying, they spread rumors that each print contained a unique code to trace bootlegs. In reality, no such code existed; the studio relied on the threat alone to protect the film from black market distribution.

The plan failed. Pirates eager to cash in on Jedi—which could sell for up to $200 per high-quality copy—opted for bold, direct approaches. Beyond the Overland Park heist, masked gunmen in Santa Maria, Calif., threatened theater staff, forcing them to surrender the film. In Columbia, S.C., a print vanished before the manager arrived on May 24, the day before the premiere. Despite multiple films being stored, only Jedi was taken.

Fox and Lucasfilm publicly denounced the thefts, with Lucasfilm president Robert Greber labeling the acts “outrageous” and blaming consumers. “Anyone who thinks owning a pirated tape is fashionable is complicit,” he stated.

The Motion Picture Association of America, tasked with combating piracy, offered a $500 reward for the stolen prints. In England, where additional reels were missing, Fox increased the bounty to $7000. No one came forward to claim the reward.

StarWars

Days after the South Carolina theft, the film was found abandoned on a dirt road, its canisters still sealed. The thieves seemed to have second thoughts about copying it. However, in Overland Park, Riddick remained determined. He hid the film in his parents’ basement for several days before approaching a local video store. The manager hesitated, and when Riddick left to give him time to decide, the manager alerted the FBI.

Law enforcement orchestrated a sting in Kansas City, with two agents pretending to be a married couple. They lured Riddick to a hotel room to negotiate the sale. Riddick initially demanded $12,000 for Jedi but settled for $10,000. After presenting one reel as evidence, he was arrested. In December 1983, the 19-year-old received five years of probation and was mandated to complete 120 hours of community service.

When questioned by police, Riddick admitted his actions were driven by anger toward his father.