If you frequently explore the realms of #BookTok, you’ve likely encountered Sarah Scannell’s elaborate murder board. Spanning almost an entire wall of her San Francisco home, it features 100 pages with jagged edges, meticulously arranged using blue painter’s tape in a configuration only Scannell understands. You might have even observed its transformation—initially linked with white string, she has now switched to a more intuitive system of color-coded sticky tabs.

Her mission isn’t to uncover a single killer but potentially up to six. Unlike typical detectives, Scannell faces a unique challenge: she doesn’t even know the identities of the victims.

For several weeks, Scannell has been tackling the notoriously complex literary puzzle known as Cain’s Jawbone. Created by the renowned crossword pioneer Edward Powys Mathers and initially released in 1934, the puzzle faded into obscurity for years until a serendipitous encounter at a UK literary museum sparked its revival in 2019.

Thanks to Scannell’s engaging and humorous TikTok videos tracking her journey, approximately 80,000 new copies are being distributed to bookstores and homes worldwide. In the publishing world, where selling 5,000 copies in a week can secure a spot on The New York Times bestseller list, this resurgence is remarkable for an 87-year-old puzzle linked to the origins of cryptic crosswords and the development of experimental fiction—a puzzle solved by only four known individuals to date.

“A Novel Problem”

Image courtesy of Unbound

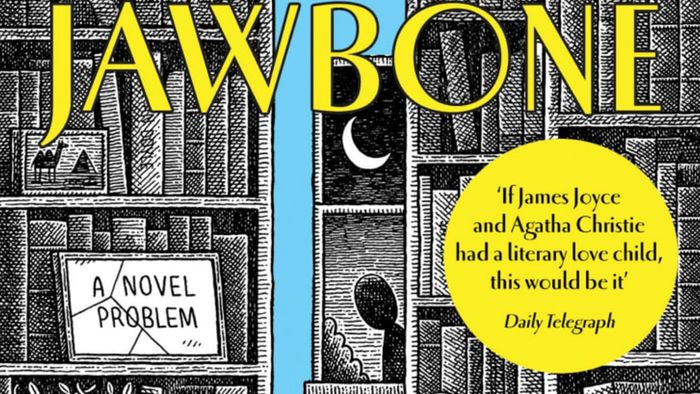

Image courtesy of UnboundThe premise of Cain’s Jawbone is straightforward yet daunting: An epigraph at the book’s beginning explains that its pages were mistakenly printed out of sequence, leaving readers to determine the correct order. With countless possible arrangements, only one sequence is accurate. Solving it allegedly reveals six murder victims and their killers—if one can navigate the labyrinth of obscure literary and historical allusions, which may serve as vital clues or deliberate distractions.

Additionally, the puzzle may include cryptic Biblical references. Mathers’ tendency to incorporate scripture-based hints in his puzzles led many to mistakenly believe he was a clergyman. The title Cain’s Jawbone alludes to the weapon Cain purportedly used to slay his brother: an ass’s jawbone.

When Scannell first noticed the book at San Francisco’s Green Apple Books earlier this year, she was unaware of its history. It was the gothic, Gorey-inspired cover art by Scottish cartoonist Tom Gauld that drew her in. Though she didn’t purchase it immediately, the book lingered in her thoughts. Despite never having read a murder mystery, Scannell is passionate about logic puzzles.

Even after acquiring Cain’s Jawbone, Scannell hesitated to begin. She explains to Mytour, “I couldn’t figure out the best physical approach to the project”—a task requiring the removal and rearrangement of all 100 pages to uncover coherence. However, after reorganizing her bedroom and discovering an empty wall, she knew precisely how to utilize the space. Cue the Pepe Sylvia meme.

Sarah Scannell's Cain's Jawbone murder board, before the addition of color-coded sticky tabs. | Courtesy of Sarah Scannell.

Sarah Scannell's Cain's Jawbone murder board, before the addition of color-coded sticky tabs. | Courtesy of Sarah Scannell.Securing space for an elaborate murder board was just the start. Scannell’s initial move toward solving the puzzle was to read all 100 pages in their printed order, aiming to “grasp character names and key events,” she explains. Those hoping to assemble sentence fragments for clues would find no help—each page starts with the beginning of a new sentence. Additionally, modern solvers must navigate Mathers’ ornate, antiquated prose.

“I knew it would be confusing, but I didn’t fully grasp how difficult it would be to interpret 1930s language,” Scannell shares with Mytour. While Google is a useful tool, the real challenge often lies in determining what to search for. Scannell believes she’s overlooked clues that are right in front of her, simply because the nearly century-old British English is so unfamiliar that she doesn’t even recognize them as hints. “There are numerous instances of language and societal norms that readers are assumed to understand—elements that a modern reader wouldn’t even think of as part of the puzzle,” Scannell explains. “This already impossible challenge becomes even more daunting with time.”

This would likely have delighted the creator of Cain’s Jawbone, whose notoriously difficult crossword puzzles once captivated audiences worldwide.

Edward Powys Mathers: Father of the Cryptic Crossword

If you’ve ever tackled one of these, you owe your gratitude to Edward Powys Mathers. | Spauln // iStock via Getty Images Plus

If you’ve ever tackled one of these, you owe your gratitude to Edward Powys Mathers. | Spauln // iStock via Getty Images PlusEven if you’ve never come across Edward Powys Mathers’s creations, his influence is likely familiar to you. Born in 1892, Mathers was a celebrated translator, a distinguished literary critic, and a skilled poet, but he achieved his greatest acclaim as a crossword creator for the British newspaper The Observer, a role he maintained from 1926 until his passing in 1939.

According to Roger Millington, author of Crossword Puzzles: Their History and Their Cult, Mathers first discovered crossword puzzles in 1924 but soon grew tired of the “dictionary clues,” which relied on synonyms, prevalent in American puzzles. Instead, he preferred “cryptic clues,” which demanded lateral and creative thinking. While Mathers didn’t invent cryptic clues, he was the first to use them exclusively, abandoning dictionary clues entirely.

Beyond his notoriously challenging clues, Mathers was a trailblazer in crossword design, introducing various formats and styles. If you’ve ever solved a barred-grid puzzle, which uses thick black lines instead of squares to mark the end of answers, you can credit (or perhaps curse) Mathers, who created the format. As noted in Alan Connor’s 2013 book Two Girls, One on Each Knee, Mathers popularized themed crosswords and was among the first to craft clues as gimmicks like knock-knock jokes and rhyming couplets.

Mathers initially designed puzzles as games for friends but soon caught the attention of The Saturday Westminster newspaper. When the paper closed, he joined The Observer, adopting the pseudonym “Torquemada”—a nod to Tómas de Torquemada, a notoriously harsh Grand Inquisitor of the Spanish Inquisition. His reasons for concealing his identity remain unclear, but it wasn’t his first time publishing under a false name. His 1920 work The Garden of Bright Waters, a collection of poems purportedly translated from anonymous Asian and Middle Eastern sources, included verses by J. Wing and John Duncan—fictional personas created by Mathers to disguise his own contributions.

As Torquemada, Mathers became an international sensation. The Observer awarded prizes for the first three correct solutions to each puzzle, sparking intense competition—up to 7000 entries arrived weekly. (An estimated 20,000 additional enthusiasts solved the puzzles without competing.) Entries poured in from as far as Alaska, India, and West Africa.

Little is documented about Mathers’s puzzle-creation process. An essay by his widow, included in a 1942 compilation of Torquemada puzzles, mentions that he could craft a relatively simple crossword (by his standards) in roughly two hours, though it provides few specifics. According to Millington’s 1977 book Crosswords, Their History and Their Cult, Mathers frequently worked with his wife to design puzzles. After selecting a theme and compiling a list of desired words, Rosemond Crowdy Mathers often handled the diagram.

To grasp Mathers’s style, consider this frequently cited example of his notoriously challenging clues: “Creeper formed of Edmund and his son Charles.” Solving it requires recognizing Edmund and Charles Kean, a father-son acting duo last seen together in an 1833 staging of Othello. Next, you’d rearrange “Keans” to reveal the “creeper”: SNAKE. Picture 100 pages filled with similarly obscure, antiquated references, and you’ll have a sense of what awaits in Cain’s Jawbone.

The origins of Mathers’s most perplexing puzzle remain shrouded in mystery. Cain’s Jawbone debuted in 1934 as the final entry in The Torquemada Puzzle Book, a compilation of crosswords, anagrams, and other “verbal pastimes.” Published by Victor Gollancz Ltd., the same firm behind George Orwell’s memoir Down and Out in Paris and London, the book offered a substantial cash prize of £25—equivalent to over £1800 or roughly $2400 USD today—for the first correct solution, as advertised in a 1934 Observer ad.

The publisher received two correct solutions, both submitted on the same day. The £25 prize went to W.S. Kennedy, whose entry was opened first, while the other solver, S. Sydney-Turner, received a “special consolation cheque.” However, the solution was never recorded, and the puzzle faded into obscurity—until it was rediscovered years later at Shandy Hall, a museum located in the former home of Laurence Sterne, renowned for his 1759 experimental novel The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman.

The Laurence Sterne Connection

Laurence Sterne. | Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Laurence Sterne. | Hulton Archive/Getty ImagesHow did the fate of a notorious 1934 logic puzzle become linked to the legacy of an 18th-century novelist known for his perplexing works? To grasp this connection, we must view Cain’s Jawbone not merely as a challenging puzzle but as a literary creation.

“When I first arrived at Shandy Hall, I aimed to help visitors understand why Tristram Shandy played a pivotal role in the evolution of the novel,” Patrick Wildgust, curator of Shandy Hall, explains to Mytour. As noted on the Laurence Sterne Trust’s website, readers and critics were baffled by The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman upon its release. Sterne boldly experimented with both the structure and content of his novel. The work is rife with risqué humor, lengthy tangents, and “visual elements” like blank pages and entirely black pages. At one point, a 10-page chapter seems to be missing, allegedly removed by the narrator because it outshone the surrounding material.

“The fact that it was written in 1759 can pose challenges for modern readers,” Wildgust notes, “so I sought to draw parallels with books that defy the conventional ‘beginning, middle, end’ structure and offer more experimental narratives.”

One of Tristram Shandy's black pages. | British Library // Public Domain

One of Tristram Shandy's black pages. | British Library // Public DomainAmong those books was B.S. Johnson’s The Unfortunates, which Wildgust has used to “illustrate how a ‘book’ can also be a box containing loose pages.” Wildgust notes that Johnson drew inspiration from Turkish-born author Marc Saporta’s 1962 experimental work Composition No. I, a novel printed as 150 unbound, single-sided pages meant to be read in any sequence.

Wildgust wasn’t the sole Sterne enthusiast captivated by The Unfortunates. During a 2018 visit to Shandy Hall, John Mitchinson, co-founder of the independent press Unbound, mentioned to Wildgust that he had recently discussed Johnson on a podcast. This led Wildgust to retrieve a copy of The Torquemada Puzzle Book, donated by Sterne scholar Geoffrey Day, who had owned it for years but couldn’t solve it. Wildgust was instantly intrigued—the book’s experimental, interactive nature fit perfectly within Shandy Hall’s collection, which also includes Raymond Queneau’s 100,000,000,000,000 Poems, a set of 10 sonnets with pages sliced into 14 strips for countless combinations; Padgett Powell’s The Interrogative Mood, a novel written entirely in questions; and Geoff Ryman’s 253, initially released online as a series of hypertext links.

Wildgust was fascinated by Cain’s Jawbone and sought to uncover its solution. In 2016, he enlisted The Guardian’s help, and the newspaper issued a public appeal on his behalf. His quest eventually brought him to John Price, who had obtained a copy of The Torquemada Puzzle Book in the 1980s and placed his own plea for help in a crossword magazine in 1988. Price received the solution from a Hampshire, England, nursing home resident, who had solved the puzzle when it was first published and still possessed a congratulatory note from Torquemada as proof.

With the puzzle’s solution in hand, Wildgust and Mitchinson chose to re-release Cain’s Jawbone through Unbound, a publisher known for crowdfunding its projects. The 2019 campaign for Cain’s Jawbone exceeded its funding goal by more than double, with over 900 supporters contributing at least $30 for a boxed edition featuring 100 loose cards. Staying true to tradition, a new prize was introduced: £1000 for the first person to solve it.

Only one individual triumphed: British writer, comedian, and crossword creator John Finnemore, who later became Neil Gaiman’s co-writer for the second season of Good Omens. Initially, Finnemore thought the puzzle was beyond his abilities, but fate intervened. “The only way I’d have a chance was if I were somehow stuck at home for months, with no place to go and no one to meet,” Finnemore explained to The Telegraph in 2020. “Unfortunately, the universe listened.”

Finnemore spent roughly four months during the 2020 lockdown working on the puzzle, eventually solving it and claiming the prize. With his success, the total number of people who have solved Cain’s Jawbone now stands at four: the two original winners, the man who shared the solution with Price, and Finnemore.

A paperback version of Cain’s Jawbone was released in February 2021, and the story might have ended there—if Scannell hadn’t stumbled upon a copy at her local bookstore months later. Scannell posted her first TikTok video about the puzzle in mid-November, which quickly went viral, amassing nearly 6 million views to date.

In November, Unbound initiated a print run of 10,000 additional copies to meet the unexpected demand. Despite this, booksellers were inundated with requests, prompting the publisher to announce a further 70,000-copy print run in early December. A new competition was also launched: anyone who submits a correct solution by December 31, 2022, will receive a £250 credit (approximately $333) for other Unbound titles.

Scannell is committed to meeting the deadline. “People keep asking if I’m worried someone will solve it before me, now that 6 million people are involved,” she says. “But I truly don’t mind. I’m doing this primarily for fun, so my only aim is to submit an answer by the competition’s end next December. I’ve already had my moment in the spotlight with all this media attention, so now I’m just enjoying the journey.”

Regardless of whether others solve the mystery of Cain’s Jawbone, Wildgust views its resurgence as a victory not only for puzzle enthusiasts but also for experimental literature that redefines the boundaries of what a novel can be.

“Cain’s Jawbone experiments with language, ideas, and narrative structure, and I thought it would be intriguing to see if modern readers would find it as captivating, entertaining, and unconventional,” Wildgust remarks. “It appears to have succeeded.”