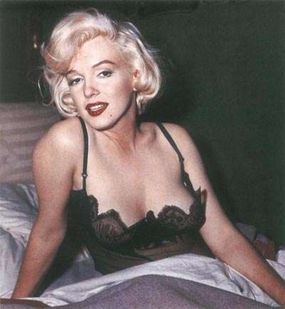

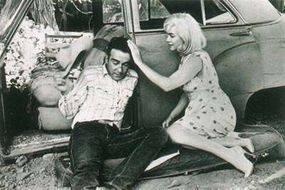

Photographs like this one reveal the immense pressure Marilyn endured during her life. Explore more images capturing Marilyn Monroe's journey.

Photographs like this one reveal the immense pressure Marilyn endured during her life. Explore more images capturing Marilyn Monroe's journey.Marilyn Monroe rose to stardom through her iconic film roles and appeared to find contentment with her third spouse, playwright Arthur Miller. However, Marilyn's erratic conduct and growing reliance on Miller to navigate daily challenges placed significant stress on their marriage. This tension escalated after Marilyn stumbled upon Miller's private journal, an incident so frequently recounted that its true emotional toll on her remains hard to fully comprehend.

Miller's journal contained candid and unfavorable reflections about Marilyn and their relationship. Some reports suggest his entries expressed frustration with her behavior during the filming of The Prince and the Showgirl, while others indicate he drew comparisons between Marilyn and his former wife.

Over time, the narrative grew more dramatic with each retelling, including versions shared by Marilyn herself. One such account alleges that Miller's private writings described his new wife using derogatory terms like "whore."

Regardless of the precise content of Miller's notes, some of Marilyn's closest confidants, such as the Strasbergs, believed that her discovery was a devastating blow that marked the decline of her marriage. Miller, however, has consistently refuted claims that this incident had any catastrophic impact on their relationship.

Marilyn Monroe Photo Collection

Despite the personal and professional struggles Marilyn faced during filming, The Prince and the Showgirl has emerged as one of her most celebrated works.

Expertly crafted and visually stunning, thanks to Jack Cardiff's cinematography, the film follows the tale of an early 20th-century American showgirl who shares a fleeting yet transformative encounter with the rigid Grand Duke Charles, Prince Regent of Carpathia. Over the course of their evening, the humble showgirl helps reconcile the Prince with his estranged son, imparting lessons of respect and equality.

The unlikely pairing of Marilyn Monroe and Laurence Olivier elevates this refined comedy. Marilyn's portrayal of Elsie Marina, with her innocence and authenticity, provides the perfect counterbalance to Olivier's portrayal of the arrogant Prince Regent.

Marilyn's iconic blend of innocence and allure is brilliantly showcased once more. While Elsie's seductive appearance initially captivates the Prince, her inherent kindness and natural wisdom inspire him to become a more just father and a progressive leader.

Much like Cherie in Bus Stop mirrored the actress who played her, Elsie Marina also reflected the real Marilyn Monroe, albeit in a less somber manner.

While Cherie sought respect, echoing Marilyn's lifelong pursuit, Elsie's connection to the actress was more playful. Similar to Marilyn, Elsie is perpetually late, even for her royal rendezvous, and is often characterized as possessing a childlike charm.

Just as Marilyn experienced a wardrobe malfunction during the press conference with Olivier, Elsie's dress strap snaps in the Prince's presence. In reality, Marilyn's insecurities and habits caused delays and exasperation, but on screen, these traits were portrayed as charming quirks.

Marilyn Monroe's blending with her on-screen personas was something she personally disliked. However, in The Prince and the Showgirl and Bus Stop, this fusion may have allowed her fans to embrace the less polished aspects of her real-life character, many of which were sensationalized by the media.

Marilyn's role in The Prince and the Showgirl catapulted her into the global spotlight. Even before the film wrapped, she was invited to a Royal Command Film Performance in the presence of Queen Elizabeth. Alongside other cinematic luminaries, Marilyn was introduced to the Queen, who praised her graceful curtsy.

Following the film's release, which garnered widespread praise, especially in Europe, Marilyn received Italy's David di Donatello Prize for Best Foreign Actress of 1958 and France's Crystal Star Award for Best Foreign Actress.

These accolades are often regarded as the European counterparts to the Oscar. However, Marilyn was once again overlooked by Hollywood during the Academy Award nominations, missing her chance for the prestigious honor.

After returning to the United States, Marilyn and Miller sought solace in a secluded cottage they rented in Amagansett, Long Island. During this time, Miller penned several short stories, including "Please Don't Kill Anything," inspired by Marilyn's deep empathy for all living beings, and "The Misfits."

Marilyn found moments of tranquility and much-needed rest in Amagansett, though her struggles with insomnia persisted. After the demanding London experience, the couple was committed to nurturing their life together.

Free from the stress of her professional life and the anxiety of feeling undervalued in Hollywood, Marilyn once remarked, "Movies are my career, but Arthur is my everything."

From early 1957 through the summer of 1958, Marilyn and Miller found renewal and peace during their time in Amagansett, Long Island.

From early 1957 through the summer of 1958, Marilyn and Miller found renewal and peace during their time in Amagansett, Long Island.Their tranquil retreat was occasionally disrupted by a few disheartening events. In May 1957, Miller's trial for contempt of Congress concluded. Marilyn publicly expressed her belief in her husband's innocence, but Miller was found guilty on two counts of contempt. He was given a 30-day suspended sentence and fined $500.

While the punishment was not severe, Miller had vigorously fought for acquittal on principle. He decided to appeal the verdict, which was ultimately reversed in August 1958.

The spring of 1957 marked another significant moment in their lives.

Marilyn ended both her personal and professional ties with Milton Greene. Their once-close friendship had faded significantly after her marriage to Miller, and their business partnership quickly fell apart during the making of The Prince and the Showgirl.

While the group was in London, Greene tried to establish a British branch of Marilyn Monroe Productions, a move Miller saw as an underhanded business maneuver conducted without Marilyn's knowledge.

Marilyn also disliked Greene's friendly rapport with Olivier and suspected him of sending antiques to the U.S. while charging the expenses to Marilyn Monroe Productions.

Once back in New York, communication between the two partners broke down entirely. Marilyn had placed such unwavering trust in Greene that any action he took for personal gain, even if legally sound, felt like a profound betrayal to her.

With Miller and his legal team's assistance, Marilyn chose to cut ties with Greene and filed a lawsuit to gain full control of Marilyn Monroe Productions. Greene ultimately settled the dispute by accepting $100,000 for his stake in the company.

Regardless of the reasons for the breakup of the Greene-Monroe partnership, Greene's efforts on Marilyn's behalf cannot be overlooked. Both Bus Stop and The Prince and the Showgirl — projects Greene handpicked for Marilyn — were completed within budget and achieved both critical acclaim and commercial success.

The most crushing blow to Marilyn's emotional and psychological well-being came in the summer of 1957. She had discovered she was pregnant in June, a joyous event that filled her with happiness.

Marilyn had a deep love for children and was actively involved in charitable work for them. She was especially devoted to Miller's two children from his previous marriage and maintained a close relationship with DiMaggio's son throughout her life.

Miller once remarked, "To truly understand Marilyn, you need to see her with children. They adore her; her outlook on life mirrors their simplicity and honesty."

Tragically, Marilyn was unable to carry her pregnancy to term. A few weeks in, she experienced severe physical pain, prompting Miller to call an ambulance to take her to Doctor's Hospital in New York. Doctors diagnosed her with an ectopic pregnancy and had no choice but to perform surgery to end it.

In the weeks after her miscarriage, Marilyn became increasingly withdrawn and sad. To lift her spirits, Miller shared his plans to adapt "The Misfits" into a screenplay tailored for her.

He intended to expand the role of Roslyn, a character only briefly mentioned in the original story, and make her the focal point of the film. While Marilyn liked the idea, she remained deeply depressed. Her reliance on sleeping pills — possibly as a means of escape — grew significantly during this time.

At one point, she overdosed on medication, though it remains unclear whether this was a deliberate act of self-harm or an attempt to numb her emotional pain. Marilyn's mood stayed low, and she avoided public appearances until late January 1958.

While in England, Miller had sold his cherished Connecticut home. When a 300-acre farm near his former Roxbury property became available, he quickly bought it.

Miller, a quiet and introspective writer, cherished the peace of rural life, though Marilyn often missed the energy of New York City. The couple split their time between the tranquility of their farm and Marilyn's new apartment in the city. Miller set up workspaces in both locations, where he continued refining his screenplay adaptation of "The Misfits."

After nearly two years away from the screen, Marilyn returned to filmmaking with Some Like It Hot. Discover more about her role in this iconic movie on the following page.

Marilyn Monroe in 'Some Like It Hot'

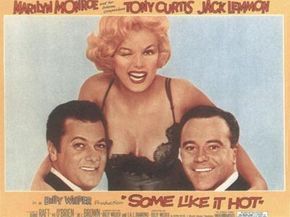

A clever marketing campaign showcased the star-studded ensemble of Some Like It Hot.

A clever marketing campaign showcased the star-studded ensemble of Some Like It Hot.Following the completion of The Prince and the Showgirl in late 1956, Marilyn stayed away from movie sets until mid-1958. This nearly two-year gap marked a period where she struggled, with limited success, to overcome personal challenges.

On August 4, 1958, Marilyn started filming Some Like It Hot under director Billy Wilder. The production was plagued by intense conflicts, health issues, personal setbacks, and bitter disputes.

Yet, the film also became her most lucrative and widely celebrated achievement. The irony of her life was that such extreme highs and lows were frequently intertwined.

A humorous take on the gangster era in Chicago, Some Like It Hot follows two musicians who accidentally witness a mob-related shooting reminiscent of the St. Valentine's Day Massacre.

To flee Chicago and avoid mob retaliation, the two friends, portrayed by Tony Curtis and Jack Lemmon, disguise themselves as women and join an all-female band traveling to Florida. Marilyn stars as Sugar Kane, the band's quirky ukulele player and singer, who forms a bond with the two new "band members."

Curtis's character, a womanizer, develops feelings for Sugar, but the ambitious blonde has shared her dream of marrying a millionaire. The farce of mistaken identities grows more complicated when Curtis adopts a second disguise as a wealthy oil tycoon to win Sugar's heart.

A hilarious subplot showcases Jack Lemmon's knack for physical comedy: While posing as a woman, Lemmon is relentlessly pursued by an elderly millionaire, Osgood Fielding III, played by the expressive comic actor Joe E. Brown.

Throughout the story, the two male leads must remain vigilant, as the gangsters are relentless in their pursuit to eliminate them.

Marilyn quickly recognized that Sugar Kane, as initially written, served primarily as a foil to the comedic antics of the two male leads.

She urged Wilder and his co-writer I.A.L. Diamond to enhance the script by adding elements that would flesh out Sugar Kane's character and give her a more active role in the humor.

One of the revised scenes features Sugar's first appearance, where she rushes to catch a train, teetering on high heels. The rewrite gave Marilyn a chance to showcase her comedic timing, as a burst of steam from the train hilariously hits her swaying figure.

This playful, slightly risqué moment, combined with Sugar's startled reaction, delivers a hearty laugh and instantly sets the tone for Marilyn's lively and spirited performance.

Marilyn was delighted with the new scene Wilder and Diamond created. She aimed for her character to stand out in the slapstick comedy central to a story about two men pretending to be women.

By portraying Sugar as a genuine eccentric rather than a stereotypical airhead, Marilyn both utilized and redefined her public persona.

The decision to film Some Like It Hot in black and white was initially a significant source of disagreement for Marilyn.

Despite being an independent production distributed by United Artists, Marilyn's latest contract with Fox required all her films to be shot in color. She believed color showcased her best and resisted the idea of shooting her comeback film in black and white.

Marilyn eventually agreed after Wilder showed her color test footage of Lemmon and Curtis in heavy makeup, which appeared unnaturally green on film.

As filming progressed, Wilder found that Marilyn's dedication to her character and the film's quality was overshadowed by bigger issues. Her chronic lateness and frequent absences disrupted production, exceeded the budget, and nearly shattered the morale of the cast and crew.

Often arriving hours late, Marilyn left costars Lemmon and Curtis waiting on set, fully dressed in their elaborate costumes and makeup. Even when she did show up, simple lines often required dozens of takes to get right.

Marilyn's struggle with multiple takes had always been an issue when she felt anxious or unsure. During this period, her reliance on medication and growing alcohol use exacerbated the problem.

Her difficulty delivering lines like "Where is that bourbon?" in fewer than 40 takes has become legendary. Her costars, especially Curtis, grew frustrated not only because her delays made for exhausting workdays but also because their own performances suffered with each additional take.

Curtis's frustration with Marilyn's delays led him to mock and criticize her off-camera. His infamous remark about Marilyn — "Kissing her is like kissing Hitler" — highlights the intense tension and animosity that plagued the set.

Unfortunately, these anecdotes have led many fans to believe Marilyn was perpetually disoriented or overwhelmed during filming, which isn't accurate. Some scenes, like the beach exteriors filmed at California's Hotel del Coronado, were completed in just one or two takes.

Director Billy Wilder's rapport with Marilyn, which started during The Seven Year Itch, worsened significantly while making Some Like It Hot. After filming wrapped, Wilder made several critical comments about her to the media.

The tough-minded director, who experienced back spasms during production, told a reporter that now that the film was done, "[I can] look at my wife again without feeling the urge to hit her just because she's a woman."

Marilyn and Miller found the remark especially harsh, as Marilyn suffered another miscarriage after production ended. It was believed that the physical and emotional toll of filming contributed to the miscarriage.

While Curtis clearly had no fondness for Marilyn, Some Like It Hot remains his most iconic and enduring film.

While Curtis clearly had no fondness for Marilyn, Some Like It Hot remains his most iconic and enduring film.Two years later, at a party for Wilder's next film, The Apartment, Marilyn and the acclaimed director reconciled. Unverified rumors at the time suggested Wilder was open to collaborating with Marilyn on a third project.

Wilder's admiration for Marilyn's unique screen presence is evident in his praise of her "high voltage" energy and "luminous" charisma.

Reflecting on Marilyn's role in Some Like It Hot, Wilder noted, "Marilyn Monroe was incredibly sensitive, challenging, and disorganized. ... Sometimes we had to piece together shots from different takes to create the illusion of a cohesive performance; but there were moments when she was absolutely extraordinary; one of the finest comediennes."

Since Marilyn's passing, Wilder's views on the iconic actress have remained mixed, often contradictory. His conflicting statements highlight both his respect for her talent and his lingering frustration with her unprofessional behavior and lack of consideration for her costars.

Wilder's most revealing remark about Marilyn appeared in columnist Earl Wilson's 1971 book, The Show Business Nobody Knows. He reflected, "I miss her. Working with her was like going to the dentist. It was hell while it lasted, but once it was over, it felt incredible."

Looking back, the comedic genius of Some Like It Hot overshadows the challenges faced during its production. Some film experts consider it Wilder's greatest work, while others rank it as the best American comedy of the sound era.

As a parody of gangster films, it stands unmatched. Biographers of Monroe often view this film as the pinnacle of her acting career; her innocent persona was utilized perfectly, playing a crucial role in the movie's triumph.

Some Like It Hot encapsulates the recurring themes in Wilder's films. Many of his works involve some form of deception — a murder plot in Double Indemnity, a reporter exploiting tragedy in The Big Carnival, or the secret lives of unfaithful businessmen in The Apartment.

Despite being shot in black and white,

the film retains all of Marilyn's undeniable charm.

While Wilder's characters are rarely entirely villainous, they often exhibit cynicism, corruption, or self-interest, frequently disregarding the emotions or welfare of others.

Wilder often highlighted their deceitful nature by introducing a contrasting character — an innocent individual who becomes either captivated or victimized by the world's moral decay.

In Some Like It Hot, Sugar's genuine nature contrasts sharply with the duplicity of the male leads. The two musicians deceive the all-female orchestra with their disguises, while Curtis further misleads Sugar by posing as a wealthy oil tycoon. On a more comedic note, Lemmon's character misleads millionaire Osgood Fielding III by feigning romantic interest.

Although Sugar, momentarily enchanted by the idea of being courted by a supposed oil magnate, briefly tries to act like a socialite, she remains transparent about her thoughts and emotions, even as the male characters work hard to hide their true selves.

Wilder's ironic, often biting perspective on life is evident in the story's conclusion, where all the deception is unveiled, yet little to no repercussions follow.

Curtis's character ultimately wins Sugar's heart, while Osgood Fielding remains unfazed upon discovering Lemmon's character is a man. "Nobody's perfect," quips Joe E. Brown, encapsulating Wilder's wry acceptance of an imperfect world.

Jack Lemmon's energetic and hilariously sharp performance is a standout in Some Like It Hot, but it's Marilyn's radiant presence and clever portrayal of Sugar that elevate the film to something extraordinary.

While Sugar is crucial to the story, and Marilyn Monroe's image perfectly conveys the innocence the role demands, Marilyn went further to deepen the character. Her dedication to authenticity, rooted in her Method training, infused Sugar with a relatable humanity.

Some Like It Hot relied on the cast's ability to master physical comedy and exaggerated farce. Despite their personal conflicts, Marilyn, Curtis, Lemmon, and the rest of the ensemble (including veterans George Raft and Pat O'Brien, who cleverly parodied their own personas) rose to the challenge.

Together, they crafted an enduring American classic. As the production's difficulties fade into history, the film itself will remain unforgettable. Some Like It Hot — and Marilyn's remarkable performance — will stand the test of time.

Sadly, Marilyn and Jack Lemmon never shared the screen again after Some Like It Hot.

Sadly, Marilyn and Jack Lemmon never shared the screen again after Some Like It Hot.Some Like It Hot received six Academy Award nominations, though Marilyn was notably absent from the Best Actress category. The film secured only one Oscar, for Best Costume Design in a black-and-white film.

However, Marilyn's performance was not entirely overlooked; she earned a Golden Globe Award for Best Actress in a Comedy or Musical and continued to receive glowing reviews.

As the 1950s came to an end, the contrast between Marilyn's chaotic personal life and her dazzling stardom grew more pronounced than ever.

Two tragic pregnancies and her growing reliance on drugs and alcohol as an escape took a toll on Marilyn, leaving her emotionally fragile in private and increasingly withdrawn around strangers.

In June 1959, Marilyn underwent surgery in hopes of improving her chances of conceiving a child. Unfortunately, the procedure was unsuccessful, deepening her insecurities about her femininity.

In her public life, Marilyn's fame soared to such heights that she was invited to meet Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev during his 1959 visit to the United States. She traveled to Los Angeles to attend a special luncheon hosted by Twentieth Century-Fox, joining other celebrities and studio executives.

While the private Marilyn struggled with her sense of womanhood, the public Marilyn embodied it effortlessly. Reflecting on her encounter with the influential world leader, Marilyn later said, "Khrushchev looked at me like a man looks at a woman."

Next, Marilyn starred in the musical comedy Let's Make Love. Learn more about her role in this film in the following section.

Marilyn Monroe in 'Let's Make Love'

In January 1960, Marilyn prepared to start filming Let's Make Love. Here, she is seen relaxing with Arthur Miller, actress Simone Signoret, and her co-star Yves Montand.

In January 1960, Marilyn prepared to start filming Let's Make Love. Here, she is seen relaxing with Arthur Miller, actress Simone Signoret, and her co-star Yves Montand.Arthur Miller finished the script for The Misfits in 1958, around the time Marilyn began working on Some Like It Hot. The Millers expected to start filming The Misfits as soon as Marilyn completed the Wilder comedy.

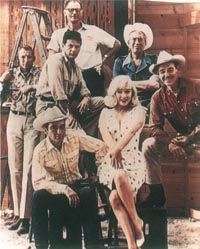

Miller had already assembled a stellar cast and crew for the project: John Huston signed on to direct, while Clark Gable, Eli Wallach, and Montgomery Clift were set to co-star. Frank Taylor, a publishing executive and Miller's close friend, was brought on as producer.

Taylor, Miller, and Marilyn established their own production company specifically for this film. Everyone was eager to begin, as Miller's profound and introspective script was expected to highlight Marilyn's acting abilities like never before.

However, Twentieth Century Fox dashed their plans by reminding Marilyn of her contractual obligations to the studio. She had committed to four films in seven years but had only completed one, Bus Stop, by that point.

Fox insisted Marilyn complete a film for the studio before pursuing another independent project. Reluctantly, she agreed to star in a lighthearted musical comedy titled Let's Make Love, which seemed the least problematic of the scripts Fox presented.

Marilyn requested her husband to enhance the script with a thorough rewrite, but even the Pulitzer Prize-winning writer struggled to elevate the thin storyline.

Miller loathed the idea of revising what he called a "frivolous" script, describing it as "not worth the paper it was typed on." Nevertheless, he attempted to adapt Marilyn's role to better suit her abilities and persona.

Gregory Peck, initially set to co-star, withdrew after reading Miller's revised script, leaving the production without a male lead. Cary Grant, Charlton Heston, and Rock Hudson were approached but declined the project, citing the Norman Krasna-Arthur Miller screenplay as the reason.

Ultimately, French actor Yves Montand accepted the role.

Montand and his wife, actress Simone Signoret, held Arthur Miller in high regard and shared similar political views. The couple had even starred in the French adaptation of Miller's The Crucible, adapted by Jean-Paul Sartre.

This moment from Let's Make Love appears to reflect the personal turmoil Marilyn was experiencing at the time.

This moment from Let's Make Love appears to reflect the personal turmoil Marilyn was experiencing at the time.Marilyn had been captivated by Montand's performance in his Broadway one-man show and charmed by his French allure. The Millers were keen to form a friendship with the Montands, and the four were frequently seen together during the early stages of Let's Make Love in mid-February 1960.

Miller observed that Marilyn's moods became increasingly volatile during this period. While she seemed to come to terms with her recent miscarriage, she was far from content in her marriage. Her dissatisfaction often manifested as spiteful behavior or blatant disrespect toward her husband.

She also began distancing herself from many of her New York friends. On a brighter note, her reliance on medication lessened as she stopped taking sedatives during the day — at least on occasion.

However, according to some reports, Marilyn was consuming more medication than her new California psychiatrist, Dr. Ralph Greenson, deemed safe.

Shortly after filming for Let's Make Love began, both Miller and Signoret were called away from Los Angeles, leaving Marilyn and Montand by themselves.

It remains unclear whether the two stars began their romance during this period or if it had started earlier. Montand always maintained that Marilyn initiated the relationship; if true, he made no effort to resist her advances.

Although Miller briefly returned to Hollywood, he chose not to stay, opting to deal with his marital issues back east. If the gossip columns are to be believed, the two stars made little effort to conceal their affair.

Marilyn's psychiatric treatment was a topic of Hollywood gossip at the time, prompting columnists who were generally sympathetic to her to criticize Montand for exploiting her vulnerability.

On set, Marilyn worked harmoniously with director George Cukor and her fellow cast members — a marked improvement compared to her behavior during her previous two films. It’s likely she was inspired by Montand’s professionalism, a trait she deeply admired.

The off-screen drama surrounding Marilyn’s affair with Montand was far more captivating than the plot of Let's Make Love.

The off-screen drama surrounding Marilyn’s affair with Montand was far more captivating than the plot of Let's Make Love.Montand partially attributed her improved demeanor to his influence, stating, "She’s reached a point where she’ll do anything I ask on set. Everyone is astonished by her cooperation, and she’s always seeking my approval."

However, much of the credit belongs to George Cukor, a director renowned for eliciting exceptional performances from his actresses. Katharine Hepburn, among other legendary stars, praised Cukor’s nuanced approach to female characters.

Cukor focused less on visual flair and more on the actors’ movements, character development, and dialogue delivery. For him, the actor was the primary vehicle for storytelling.

It’s likely Marilyn felt Cukor understood her character better than previous directors had. His experience and approach may have contributed to her cooperative behavior on set.

Unfortunately, while Marilyn didn’t delay filming, two Hollywood strikes — first by the Screen Actors Guild and then by the Screen Writers Guild — halted production of Let's Make Love for more than a month.

After filming wrapped, Montand ended his affair with Marilyn. It was clear he had no plans to leave his wife, Simone Signoret.

He publicly stated, "[Marilyn] has been very kind to me, but she’s a straightforward woman without any deceit. Maybe I was too gentle and assumed she was as worldly as other women I’ve known. ... If Marilyn had been more experienced, none of this would have happened. ... Perhaps she had a fleeting infatuation. If so, I regret it. But nothing will come between me and my marriage."

In the summer of 1960, while Marilyn was filming The Misfits and Montand had returned to Los Angeles, she attempted to reconnect with him but was unsuccessful.

After finishing her film, Marilyn finally met Montand at Idlewild Airport in New York. They said their goodbyes in the back seat of her limousine.

The affair itself didn’t directly end Marilyn’s marriage to Miller, but it was another factor in its slow unraveling.

Given Marilyn’s increasingly fragile mental state and her growing detachment from reality, the relationship with Montand had a damaging impact on her life.

Despite the off-screen chemistry between Monroe and Montand, Let's Make Love is widely regarded as a lackluster musical comedy and remains one of Marilyn’s least memorable films.

Montand portrayed billionaire Jean-Marc Clement, a renowned playboy who becomes intrigued when he discovers a theater group plans to mock him in a musical performance.

Let's Make Love only shines in brief moments, particularly during Marilyn’s energetic performance of "My Heart Belongs to Daddy."

Let's Make Love only shines in brief moments, particularly during Marilyn’s energetic performance of "My Heart Belongs to Daddy."Clement, aiming to halt the production, attends a casting call for the play and is instantly captivated by Marilyn’s character, Amanda Dell, a singer-dancer. Unaware of Clement’s true identity, the director casts the billionaire to play himself in the show.

Clement seizes the chance to woo Amanda, who repeatedly voices her disdain for carefree, playboy billionaires. Predictably, Amanda falls for Clement, believing him to be a struggling actor.

The film’s supporting cast included Tony Randall and Wilfrid Hyde-White, with cameo appearances by Milton Berle, Gene Kelly, and Bing Crosby as themselves.

While these elements are somewhat formulaic, they aren’t without potential. Sadly, the weak script relies on Marilyn’s image rather than showcasing her true talent.

The film lacks depth in character development and subtlety, relying instead on reusing familiar Monroe tropes from previous movies and incorporating elements of her personal life that fans would easily recognize.

Marilyn’s character, Amanda, is a musical comedy performer who attends night school to improve herself. Amanda is a fan of Method acting, as seen when she advises Clement to imagine owning a limousine to help him embody the mindset of a wealthy man.

One of Amanda’s musical performances features her in a white, flowy, V-necked dress that gets blown upward during the act — a clear nod to The Seven Year Itch. These references, however, contribute little to the overall film.

Despite the film’s shortcomings, Marilyn’s charisma and energy shine through in one of its musical numbers — the sizzling "My Heart Belongs to Daddy."

Beyond that standout moment, the only other highlight is Milton Berle’s scene with Montand, where the seasoned comedian attempts to teach the French actor about American humor.

While most Monroe biographers consider the film a critical and commercial disappointment, initial reviews of Let's Make Love were actually mixed. Additionally, there’s no evidence the film was a box office disaster, though it certainly fell short of the success Fox executives had anticipated.

With Let's Make Love completed, Marilyn could finally focus on The Misfits. Discover more about this film on the next page.

Arthur Miller's Valentine to Marilyn Monroe

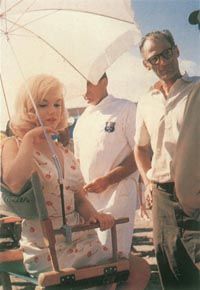

Arthur Miller penned the screenplay for The Misfits as a heartfelt tribute to his wife.

Arthur Miller penned the screenplay for The Misfits as a heartfelt tribute to his wife.In July 1960, filming finally commenced on The Misfits, Miller’s love letter to Marilyn. Directed by John Huston, written by Arthur Miller, and starring Marilyn Monroe, Clark Gable, Montgomery Clift, and Eli Wallach, The Misfits was poised to be a cinematic triumph and Marilyn’s opportunity to showcase her acting prowess.

In hindsight, both statements hold true. A poignant film with stunning visuals, The Misfits serves as both a thought-provoking allegory about the fading American West and a remarkable platform for Marilyn, who takes on the most demanding and serious role of her career.

At the time, however, the film seemed destined for failure due to Marilyn’s personal issues, which cast a shadow over the production and risked eclipsing the film’s impact.

The Misfits is an intricate allegory about three men, disconnected from society and remnants of a bygone era, who belong to a West that no longer exists.

Nevada cowboys Gay Langland (Gable) and Perce Howland (Clift) are outcasts due to their rugged independence; the airplane pilot Guido (Wallach) has been lost since his wife’s death. Together, they hunt wild mustangs, selling them to a dog food company.

Despite the strong performances of the three male leads, the film’s centerpiece is Marilyn’s character, Roslyn Tabor. Her sensitivity and otherworldly beauty captivate each of the men.

Although they are supposedly friends, the men struggle to connect with one another. Instead, they connect only with Roslyn, as she embodies something each of them craves or lacks. Each man opens up to her, offering his own interpretation of what makes her unique.

Roslyn, too, feels disconnected from society, at least temporarily, as she arrives in Reno for a divorce. Reno, known as the divorce capital of the world, serves as an ideal backdrop for a tale of isolation.

Roslyn challenges the men to face the emptiness of their lives when she begs them to spare the wild mustangs they’ve worked so hard to capture. However, the trio believes their way of life offers a freedom superior to the constraints of working for "wages."

Ironically, this very "freedom" keeps them isolated from society and detached from meaningful human connections. Their unwavering commitment to their independence is both their greatest strength and their fatal flaw.

Like the cowboys, the wild horses represent the last of a disappearing breed — a parallel the men fail to grasp. By slaughtering the horses, they are eradicating the remnants of the lifestyle they so fiercely defend. In destroying the horses, they are, in essence, destroying themselves.

In the end, Roslyn prevails. The horses are released, and she and Gay ride off together toward "that big star straight on," which will lead them "right home." Despite the absence of clear resolutions to the characters’ personal struggles, the film concludes on an optimistic note.

Unsurprisingly, The Misfits is closely associated with Miller and Monroe, but a narrative centered on a group of characters pursuing a doomed mission is also a hallmark of director John Huston’s work.

In Huston’s films, the protagonist is often a driven individual who stakes everything on a quest, much like Gay’s fervent dedication to capturing the wild mustangs.

Huston’s female characters typically interfere with the quest or distract the hero from his objectives, often portraying destructive roles.

In The Misfits, however, Roslyn serves as a positive influence, and her intervention in the cowboys’ plan to sell mustangs for dog food becomes a celebration of life.

The filming of The Misfits was an arduous ordeal. Separated from her psychiatrist and emotionally distant from Miller, Marilyn significantly increased her use of prescription drugs, a situation exacerbated by her alcohol consumption.

Her despair during the initial weeks of production deepened, threatening to consume her entirely. Miller had hoped The Misfits would rekindle their relationship, but he soon realized, "if there was a key to Marilyn’s despair, I did not possess it."

Marilyn’s resentment toward Miller grew, as she directed all her anger and frustration at him, despite his lack of justification for such treatment.

Marilyn felt let down by her marriage, likely because it failed to meet her lofty expectations for happiness. Once she felt betrayed, she cut off everyone involved from her life.

Seeking reasons to push Miller away, she criticized his screenplay for The Misfits, lamenting, "He could have written me anything, and he comes up with this. If that’s what he thinks of me, then I’m not for him, and he’s not for me."

By late August, Marilyn experienced a breakdown and was rushed to Westside Hospital in Los Angeles. As temperatures in Nevada soared above 100 degrees, her frail body was wrapped in a damp sheet and transported by plane to the West Coast.

Under the supervision of her psychiatrist and internist, Marilyn remained hospitalized for ten days, halting production entirely.

Columnist Louella Parsons highlighted the severity of Marilyn’s fragile health, stating, "She’s a very sick girl, much sicker than initially thought."

Marilyn returned to the set the following week, though filming was repeatedly interrupted throughout September due to her ongoing struggles.

Beyond Marilyn’s fragile mental and emotional state, the production faced the looming threat of other potential crises.

Marilyn and Montgomery Clift: two kindred spirits adrift in life.

Marilyn and Montgomery Clift: two kindred spirits adrift in life.Montgomery Clift, whose once-striking appearance was marred by a 1957 car accident, shared Marilyn’s reliance on alcohol and drugs. This led her to remark, "He’s the only person I know who’s in worse shape than I am."

Clift’s reputation had deteriorated to the point where insurance companies refused to cover him for films. However, thanks to the efforts of Miller, Huston, and influential Hollywood figure Lew Wasserman, insurance for the troubled actor was eventually secured.

Despite his troubled reputation and heavy drinking on set, Clift never missed a day of work and had memorized his entire role before filming started. Nevertheless, his involvement in the project caused significant concern at the time.

After The Misfits, Clift would appear in only three more films before passing away from coronary-artery disease in 1966.

Another issue on set was Paula Strasberg’s near-total control over Marilyn. The two spent significant time together, both on and off the set.

They meticulously analyzed lines, strategies, and character development, often secluded in Marilyn’s air-conditioned limousine. At one point, Marilyn even moved out of the hotel suite she shared with Miller and into Strasberg’s.

Huston’s directing style, which relied heavily on the actors’ input for character development, gave Strasberg considerable influence over Marilyn. However, Huston did not hold Strasberg in high regard and prevented her from interfering with his direction.

For Marilyn, Clark Gable’s involvement in The Misfits must have felt like a dream come true. Her admiration for Gable dated back to her childhood, when she fantasized that the dashing actor was her father.

Her supposed biological father, C. Stanley Gifford, was said to resemble Gable — as much as any ordinary man could. In 1947, Marilyn took singing and acting lessons from John Carroll, an actor often compared to Gable in appearance.

Finally, in 1954, at a party held in her honor, Marilyn got the chance to meet the King of Hollywood. They dined, danced, and happily discussed the possibility of collaborating on a film someday. She was overjoyed when Gable agreed in 1958 to play the lead role of Gay Langland in The Misfits.

Marilyn had idolized Clark Gable since she was a child. The chance to act alongside the legendary star was a dream realized for the troubled actress.

Marilyn had idolized Clark Gable since she was a child. The chance to act alongside the legendary star was a dream realized for the troubled actress.True to Marilyn’s childhood fantasies, Gable was not only a consummate professional but also a kind and considerate gentleman. Despite the grueling conditions of the The Misfits shoot, exacerbated by long delays caused by Marilyn, Gable never displayed anger or resentment toward the visibly unwell actress.

On set, Marilyn remarked, "The place was full of so-called men, but Clark was the one who brought me a chair between takes."

According to his agent, Charles Chasin, the iconic actor believed The Misfits was among the finest of his 70 films. However, privately, Gable expressed frustration with Marilyn’s behavior and hinted at his growing exhaustion from the demanding production.

Even nature seemed determined to hinder the production of The Misfits — Reno’s summer temperatures often soared to a blistering 108 degrees. With several cast members in declining health, the extreme weather became a formidable adversary.

Marilyn’s emotional turmoil during the filming of The Misfits was challenging enough, but the scorching Nevada heat added another layer of difficulty.

Marilyn’s emotional turmoil during the filming of The Misfits was challenging enough, but the scorching Nevada heat added another layer of difficulty.Despite these challenges and Marilyn’s reliance on drugs and alcohol, Huston managed to draw an extraordinary performance from his leading lady.

While some biographers claim Marilyn sleepwalked through the role, these critiques are unfair, influenced by hindsight and sensationalized accounts of her struggles with substance abuse.

In reality, Marilyn’s performance is both convincing and powerful, a testament to her Method training, which enabled her to fully embody the character of Roslyn.

Additionally, Miller’s skillful integration of the real-life Marilyn Monroe with the fictional Roslyn enhanced Marilyn’s portrayal,

as did Huston’s directing style, which allowed the actors the freedom to delve deeply into their characters.

Huston had always held Marilyn in high regard, and his respect for her endured despite the frustrations of directing The Misfits. He attributed her struggles to doctors who overmedicated her and studios that turned a blind eye.

In a 1981 interview, Huston praised Marilyn as a talented actress, "not in the technical sense, but . . . she had the ability to dig deep within herself, draw out an emotion, and deliver it."

Despite Marilyn’s dedication and the contributions of everyone involved, The Misfits received mixed reviews and underperformed at the box office — an unjust and disappointing conclusion to Marilyn’s extraordinary career.

After the filming of The Misfits, Marilyn parted ways with Miller and sank deeper into depression. Explore her downward spiral in the next section.

Marilyn Monroe's Depression

Marilyn struggled with depression after her divorce from Arthur Miller, the death of Clark Gable, and other personal challenges.

Marilyn struggled with depression after her divorce from Arthur Miller, the death of Clark Gable, and other personal challenges.By the conclusion of The Misfits shoot, Marilyn’s marriage to Arthur Miller was essentially finished. After filming ended in early November, the two departed for New York on separate flights.

On November 11, she publicly announced their separation to columnist Earl Wilson. The press descended on her New York home, and a visibly emotional Marilyn stepped out to confirm the news.

According to one Monroe biographer, reporters were so desperate to reach her that one journalist thrust his microphone into her mouth, accidentally chipping one of her teeth.

Marilyn tried to retreat from the public eye, but her plans were disrupted by the news of Clark Gable’s death on November 16. Gable had suffered a massive heart attack the day after The Misfits wrapped, and many had believed his condition was improving.

His unexpected passing was a devastating blow.

Marilyn was so overwhelmed by the news that she struggled to articulate a clear statement to the press, who relentlessly sought her reaction.

Eventually, she managed a brief comment: "This is a tremendous shock to me. I’m deeply sorry. Clark Gable was one of the finest."

men I’ve ever known."

Rumors quickly spread that Kay Gable, Clark’s young widow, who was expecting his first child, held Marilyn responsible for her husband’s death. Kay argued that the stress Gable endured during the filming of The Misfits, including the constant delays and extreme heat, contributed to his heart attack.

Upon hearing this, Marilyn plunged into a deep depression — the idea that she had played a role in the death of the man she had idolized since childhood was unbearable.

The following May, Kay Gable invited Marilyn to the christening of Gable’s son, John Clark Gable. Marilyn, feeling relieved, saw the invitation as a gesture that Kay no longer blamed her for her husband’s passing.

As the winter of 1960-61 progressed, Marilyn’s sense of despair and hopelessness deepened. Spending Christmas without Miller or Montand highlighted her isolation, though Joe DiMaggio reentered her life, rekindling their relationship.

Despite their past marital issues, the ex-couple maintained a strong bond, sparking media speculation about a potential reunion.

Marilyn traveled to Mexico in January to finalize her divorce from Arthur Miller. Shortly after, she updated her will, naming her half-sister Berniece Miracle as a primary beneficiary, despite their limited interactions over the years.

Her will also included arrangements for her mother's care and allocated funds to several friends, including her secretary, May Reis.

Lee Strasberg and her psychiatrist, Dr. Marianne Kris, were designated to receive portions of her estate. Additionally, Strasberg inherited all of Marilyn's personal belongings and wardrobe.

The will reflects the life of a woman with minimal family ties and a small circle of acquaintances, many of whom were professional associates, staff, or medical professionals rather than intimate friends.

In February 1961, Marilyn Monroe checked into the Payne-Whitney Clinic in New York, following the advice of her East Coast psychiatrist, Dr. Kris. However, she quickly felt uneasy and out of place at the facility.

Shocked by the stringent security measures, such as barred windows and glass-paneled doors for constant monitoring, Marilyn resisted being treated as if she were mentally unstable. She believed the staff paid her extra attention due to her celebrity status.

With restricted phone access, Marilyn managed to contact Joe DiMaggio in Florida. DiMaggio promptly returned to New York, secured her release from Payne-Whitney, and transferred her to Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center.

When Marilyn left Columbia three weeks later, reporters and photographers behaved disgracefully, crowding around her at the hospital entrance. They shouted intrusive questions and obstructed her path to a waiting limousine.

A team of sixteen police officers and hospital security personnel was required to escort her safely to her car. She spent the following weeks in Florida with DiMaggio, who remained a steadfast caretaker until her passing.

Alongside her fragile emotional and mental state, Marilyn also battled numerous physical ailments. In May 1961, she underwent gynecological surgery at Cedars of Lebanon Hospital in Los Angeles.

Just a month later, she was admitted to New York's Polyclinic Hospital for gallbladder surgery. Marilyn also struggled with an ulcerated colon and irregular uterine bleeding.

Due to her fragile mental and physical health, Marilyn took a hiatus from acting throughout 1961. For details about her last film, proceed to the next section.

Marilyn Monroe's Final Film

In early 1962, Marilyn is seen embracing her Golden Globe award, accompanied by Rock Hudson.

In early 1962, Marilyn is seen embracing her Golden Globe award, accompanied by Rock Hudson.At the start of 1962, Marilyn's psychiatrist, Dr. Ralph Greenson, encouraged her to purchase a home of her own, believing it would provide her with a sense of stability. Despite her immense success, Marilyn had never lived in a house she owned independently.

With Eunice Murray's assistance, Marilyn discovered a charming Mexican-style house in Brentwood, Los Angeles. The single-story property was modest yet appealing.

A decorative tile featuring a coat of arms and the Latin phrase "Cursum Perficio," meaning "I am finishing my journey," was placed near the front entrance. Tragically, Marilyn had fewer than six months left to live.

The acquisition of her new home in February 1962 and her Golden Globe Award win in March as the "world's film favorite" marked the final highlights of her life.

Although Greenson had temporarily reduced Marilyn's reliance on medication, she soon reverted to her previous patterns as challenges arose and the future appeared increasingly bleak.

In April, Marilyn went back to Twentieth Century-Fox to start filming Something's Got to Give, a modern take on the 1940 comedy classic My Favorite Wife. George Cukor was assigned as the director.

Marilyn was unimpressed with the Nunally Johnson-Walter Bernstein script from the beginning, especially since it wasn't finalized when production started. By 1962, Peter Levathes, a former advertising executive with a reputation for being tough on actors, was Fox's top production executive.

Levathes had just dealt with significant issues during the making of Cleopatra, which led to massive budget overruns. The atmosphere on the set of Something's Got to Give was extremely tense.

Despite concerns from Dr. Greenson and her internist about her ability to handle a new film, Marilyn attended hair, makeup, and costume tests at Fox. That spring, she had caught a virus, leaving her drained and physically weakened.

Acknowledging Marilyn's illness, studio executives, Cukor, and co-star Dean Martin adjusted the shooting schedule to accommodate her. However, Marilyn only managed to appear on set for six days in May.

In late May, Marilyn flew to New York for a brief visit. Peter Lawford had invited her to perform "Happy Birthday" at President Kennedy's grand birthday celebration at Madison Square Garden.

Despite battling a virus and her ongoing film obligations, Marilyn eagerly accepted the invitation. Isidore Miller, Arthur Miller's father, accompanied his former daughter-in-law to the event, where she delivered her famously sultry rendition of "Happy Birthday" to Kennedy.

While Marilyn's nude swim scene captivated photographers and intrigued the public, it did little to advance the progress of Something's Got to Give.

While Marilyn's nude swim scene captivated photographers and intrigued the public, it did little to advance the progress of Something's Got to Give.Marilyn's performance and Kennedy's playful remark ("I can now retire from politics after having 'Happy Birthday' sung to me in such a sweet, wholesome way.") take on a haunting tone given the later revelations about their affair and the tragic fate that awaited JFK.

The occasion was further tinged with irony when Lawford introduced the tardy Marilyn as "the late Marilyn Monroe."

Fox executives were furious with Marilyn for attending the Kennedy event in New York. If she was too ill to work, they argued, she shouldn’t have been well enough to travel across the country for a personal appearance.

This incident marked a shift in Fox's approach to Marilyn; from then on, they adopted a stricter stance.

Over the following two weeks, Marilyn attended work more regularly. During this period, a swimming pool scene was being filmed, where Marilyn was expected to wear a flesh-toned swimsuit to create the illusion of swimming nude.

Due to the provocative nature of the scene, several photographers were invited to take promotional photos. That night, they received an unexpected bonus when Marilyn discarded her suit and swam au naturel.

Photographers and newsreel crews rushed to capture the infamous "nude swim," during which a playful Marilyn flirtatiously revealed glimpses of her bare body to the cameras.

The camera, her one true love, stayed loyal until the very end, and Marilyn delivered as always.

On June 1, Marilyn celebrated her 36th birthday with a small surprise party organized by the cast and crew on set. This day also marked her final appearance at work. Out of 33 scheduled shooting days, Marilyn had only attended 12.

Even when she did show up, she was often hours late and rarely managed to complete more than a single page of the script daily, as reported in a studio press release. On June 8, 1962, production head Peter Levathes dismissed Marilyn from Something's Got to Give.

Lee Remick was considered as Marilyn's replacement. At the time, Remick remarked, "I'm unsure whether to feel sympathy for [Marilyn] or not. I believe replacing her was necessary. The film industry is suffering due to such behavior. Actors shouldn't be permitted to act this way."

Marilyn was terminated by Fox during the production of Something's Got to Give, marking the end of her career on a movie set.

Marilyn was terminated by Fox during the production of Something's Got to Give, marking the end of her career on a movie set.Marilyn was deeply hurt by her firing, viewing it as a personal affront. Dean Martin, likely out of loyalty or friendship, declined to proceed with the film if Lee Remick replaced her. (The project was later reimagined as a Doris Day and James Garner vehicle, released in 1963 as Move Over, Darling.)

The only remnants of Something's Got to Give are still photos, wardrobe test clips, and a few scenes, including the famous swimming pool sequence.

In these clips, Marilyn appears more radiant than ever—slender, graceful, with her hair a luminous platinum, she seems almost ethereal. This footage was first showcased to the public in Marilyn, a 1963 Fox documentary hosted by Rock Hudson.

For insights into Marilyn's rumored relationships with Frank Sinatra and John F. Kennedy, proceed to the next section.

Marilyn Monroe's Romantic Links to Frank Sinatra and JFK

Marilyn has been romantically associated with both Sinatra and JFK.

Marilyn has been romantically associated with both Sinatra and JFK.Following her separation from Arthur Miller, Marilyn started seeing Frank Sinatra and became an informal part of his "Rat Pack," a close-knit circle of entertainment industry friends with whom Sinatra shared strong personal and professional bonds.

The core members of the Rat Pack were Dean Martin, Sammy Davis, Jr., Peter Lawford, and Joey Bishop.

Marilyn and Sinatra had been acquainted for years, and some biographers suggest they might have had a relationship earlier, though no concrete proof supports this claim.

Their friendship likely rekindled during the filming of The Misfits, when Marilyn was brought to Los Angeles after her emotional collapse. Reportedly, Sinatra reached out to check on her well-being and offer his support.

Earlier, Sinatra had invited the The Misfits cast to see him perform at the Cal-Neva Lodge, which he was in the process of buying. The lodge, situated near Lake Tahoe, straddled the California-Nevada border.

Marilyn visited the lodge multiple times in the last two years of her life. (Sinatra later sold the property after his ties to organized crime were exposed in the media.)

Sinatra gifted Marilyn a small white poodle to fill the void left by the dog she lost during her divorce from Miller. With her characteristic wit, Marilyn named the dog "Maf," a playful nod to the Mafia.

Marilyn had been acquainted with actor Peter Lawford

since her early days as a starlet, when he had accompanied her to several Hollywood events.

Her connections with Sinatra and Lawford likely introduced her to John Kennedy, possibly as early as July 1960, when the young senator secured the Democratic presidential nomination. At the time, Lawford was married to Pat Kennedy, JFK's sister.

Some reports suggest Marilyn was present at the L.A. Coliseum when Kennedy delivered his acceptance speech and later attended the celebration at Romanoffs restaurant, where she was introduced to the future U.S. President.

However, some biographers argue that Marilyn and Kennedy met as early as 1951 at parties hosted by agent Charles Feldman in Los Angeles. These claims, however, lack solid evidence or reliable witness corroboration.

Deborah Gould, Lawford's third wife, claims Kennedy first met Marilyn a few months before his July 1960 nomination, during the presidential campaign.

Regardless of the timeline, it is widely believed that Marilyn Monroe and John Kennedy were romantically involved throughout 1961, if not earlier. A November 1960 column by Art Buchwald lends credibility to these theories.

The column, titled "Let's Be Firm on Monroe Doctrine," stated, "Who will be the next ambassador to Monroe? This is one of the many issues President-elect Kennedy must address in January. Clearly, Monroe cannot be left unattended. With many eager suitors vying for her attention and Ambassador Miller gone, she risks drifting aimlessly."

In the following section, you'll discover the details of Marilyn's final days and her tragic passing.

Marilyn Monroe's Death

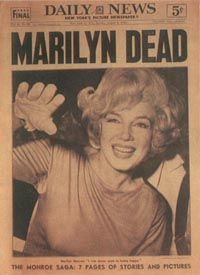

Marilyn's death left the world in shock.

Marilyn's death left the world in shock.Marilyn's firing from Something's Got to Give occurred alongside a tumultuous lifestyle: she dated multiple men, consumed excessive amounts of sleeping pills, and depended on daily sessions with Dr. Greenson to navigate each day.

It is widely believed that in 1962, Marilyn began a romantic involvement with Robert Kennedy, the very married brother of John Kennedy.

Robert, who served as Attorney General, is said to have facilitated Marilyn's exit from his brother's life. JFK's advisors reportedly viewed his affair with Marilyn as a political liability and urged him to end it.

Speculation about Marilyn's relationship with Robert Kennedy stems from multiple eyewitness accounts of their encounters, especially at Peter Lawford's Malibu beach house. However, concrete details about their affair are even scarcer than those involving Marilyn and JFK.

Accounts vary, with some biographers claiming Marilyn met RFK at a Lawford dinner party in 1961, while others suggest their introduction occurred at the New York birthday celebration in May 1962.

What is hard to ignore is that Marilyn frequently called the Justice Department—where Robert Kennedy worked—soon after her dismissal from Fox.

At this stage, the speculation takes a highly implausible direction. In the summer of 1962, Robert Kennedy and/or his advisors allegedly decided that his relationship with Marilyn—like his brother's—posed a significant risk.

This decision was influenced not only by Marilyn's fragile mental health but also by the awareness that organized crime figures were intent on undermining RFK.

As Attorney General, Kennedy had targeted prominent mobsters like Sam Giancana and Mafia-linked union leaders such as Jimmy Hoffa. Both men had publicly and privately sworn to bring down the younger Kennedy.

There is some indication that Marilyn's home was under surveillance in the weeks leading up to her death, and that she was aware of it.

Many believe that organized crime figures, keen to catch Robert Kennedy in a compromising situation, were behind the wiretaps in Marilyn's residence.

Regardless of the actual circumstances, RFK reportedly ended the relationship shortly after Marilyn was fired by Fox.

The final days of Marilyn's life have been recounted numerous times, often with conflicting details.

Frantic efforts to contact Robert Kennedy by phone are paired with rumors that Twentieth Century-Fox might rehire her to finish Something's Got to Give. Stories of her heavily medicated state contrast with her excitement about decorating her new home, while claims of her neglecting her appearance are contradicted by her pride in Bert Stern's July photo shoot.

her in July.

On August 4, 1962, Marilyn began her day chatting with her publicist, Pat Newcomb, and spent the afternoon calling friends. Dr. Greenson stopped by for a brief visit in the early evening.

The list of individuals who claim to have spoken with Marilyn on her final day is astonishing—ranging from Joe DiMaggio, Jr., to Marlon Brando, and from Sidney Skolsky to Isidore Miller.

From her bedroom, Marilyn kept making phone calls late into the night. As the evening progressed, her speech grew increasingly slurred, a common occurrence due to her heavy reliance on sedatives at the time.

Surprisingly, none of her friends were concerned enough to send someone to check on her. It is said that Marilyn called Peter Lawford that night to bid him farewell.

Sometime during the night of August 4-5, 1962, Marilyn Monroe passed away alone, her white phone still gripped in her hand.

Just as the press had pursued Marilyn relentlessly in life, they swarmed around her in death, capturing images of her covered body as it was carried from her home, into the ambulance, and to the morgue. Pat Newcomb condemned the reporters for their insensitivity, labeling them "vultures."

The publicist's harsh words might not have been entirely misplaced, as one reporter reportedly remarked, "I feel as bad as anyone about Marilyn Monroe's death. But if she had to go, at least she chose August."

Marilyn's death was officially labeled a "probable suicide." Her funeral was held on August 8 at the Westwood Memorial Park Chapel in Westwood, California.

Joe DiMaggio, with assistance from Marilyn's half-sister Berniece Miracle and business manager Inez Melson, organized the service. Rev. A.J. Soldan led the ceremony, reading the 23rd Psalm, the 14th chapter of the Book of John, and passages from the 46th and 139th Psalms.

Lee Strasberg gave a brief eulogy, and Judy Garland's "Over the Rainbow" was played. DiMaggio restricted attendance to a small group, with many of Marilyn's recent Hollywood associates notably missing.

Almost immediately, newspapers began circulating rumors about inconsistencies in the reports of Marilyn's death. The Los Angeles Herald-Examiner published unverified claims that her body had been secretly moved from the morgue.

Another article in the same newspaper highlighted significant inconsistencies in the timeline of events from that tragic night. Friends and colleagues interviewed at the time were divided over whether Marilyn had taken her own life or accidentally overdosed on sleeping pills.

Over the years, numerous self-proclaimed "investigators" have alleged that organized crime figures killed Marilyn to implicate the Kennedys, that the CIA orchestrated her death to undermine the Kennedy administration, or that the Kennedys themselves were responsible to prevent a public scandal.

None of these theories have produced sufficient evidence to support even a credible news article, much less a legal case.

Despite the lingering mysteries surrounding Marilyn's death, official investigators saw no reason to delve deeper than a surface-level inquiry. In all likelihood, no crime was committed—only the concealment of ill-advised relationships.

Some even question whether her death was a suicide, suggesting that on her final night, Marilyn may have simply sought to escape her despair through sleep, as she had done countless times before. In her confused state, she likely lost count of the sleeping pills she consumed.

In our efforts to understand the tragic struggles of Marilyn's life, we may have become fixated on unraveling the mystery of her death. Yet, any attempt to uncover the truth about her final hours remains futile. Marilyn Monroe carried her secrets to the grave.

To explore various theories about Marilyn's death, proceed to the next section.

Marilyn Monroe: Murdered?

The iconic Hollywood star radiated her natural charm during a 1959 photoshoot with photographer Philippe Halsman.

The iconic Hollywood star radiated her natural charm during a 1959 photoshoot with photographer Philippe Halsman.While Marilyn Monroe's immense popularity during her lifetime is understandable, the exponential growth of her fame after her death is seen as a cultural phenomenon, captivating biographers, critics, and fans alike.

Our enduring fascination with Marilyn is undoubtedly fueled by her untimely death and the enigmatic circumstances surrounding it.

Periodic attempts are made to convince the Los Angeles police to reinvestigate her case. During these times, speculation and rumors surge as new fragments of information emerge.

In 1974, Robert Slatzer, who claimed to have married Marilyn in 1953, wrote a book asserting that the iconic star had been murdered.

Titled The Life and Curious Death of Marilyn Monroe, the book explores her connections with the Kennedys, examines the unanswered questions about her death, and presents a provocative—though ultimately unconvincing—conspiracy theory.

Slatzer enlisted private detective Milo Speriglio to gather evidence supporting his claims. Speriglio has spent over 15 years on the case and insists he knows who killed Marilyn and why, though he lacks the proof to substantiate his theory.

In 1982, Speriglio offered a $10,000 reward for Marilyn's alleged "red diary," which he claims contains details of her conversations with Robert Kennedy. Slatzer reportedly saw the diary days before her death, and coroner's aide Lionel Grandison allegedly spotted it in the coroner's office.

Notably, Speriglio's announcement about the diary coincided with the release of his first book, Marilyn Monroe: Murder Cover-Up, which revisits Slatzer's claims and updates the investigation.

Rumors of a cover-up continue to keep Marilyn's name in the headlines, decades after her passing.

Rumors of a cover-up continue to keep Marilyn's name in the headlines, decades after her passing.Later that year, a rare book collector offered $150,000 for the diary, which

has never been found, leading many to question its very existence.

In 1986, Speriglio released a second book, The Marilyn Conspiracy, an updated take on his previous work. That year, he held a press conference urging authorities to reopen the case, but his request was rejected.

While many question the credibility of Slatzer and Speriglio's theories and findings,

the persistent rumors of murder or a cover-up ensure Marilyn's name remains in the spotlight, alongside the tributes and retrospectives that emerge on the anniversary of her death.

The murder theories add an air of infamy to her legacy, while the tributes and honors remind us that her life was far more than just romantic entanglements and a mysterious death. Both forms of attention amplify her legend, securing her a lasting place in Hollywood folklore.