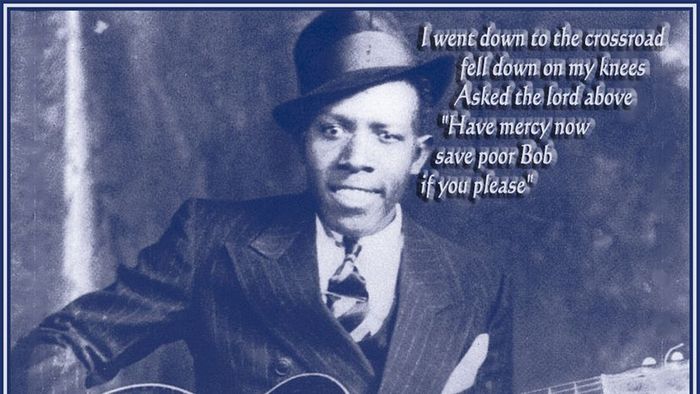

Robert Johnson, a pivotal figure in blues history and one of its greatest pioneers, passed away at just 27 years old. Ray MacLean/Flckr/CC By-2.0

Robert Johnson, a pivotal figure in blues history and one of its greatest pioneers, passed away at just 27 years old. Ray MacLean/Flckr/CC By-2.0In 1930, in Robinsonville, Mississippi, a 19-year-old Robert Johnson, an ambitious blues musician, found himself at a juke joint where Delta blues icons Son House and Willie Brown were performing to a lively crowd. During breaks, Johnson bravely took up one of the guitars to play his own tunes, but the audience was far from impressed.

"He began to play, and it was just irritating the crowd," Son House recalls in "ReMastered: Devil at the Crossroads," a Netflix documentary about Robert Johnson. "People started shouting, 'Can someone make that boy stop playing? He's driving us crazy!'"

The club owners kicked Johnson out of the Robinsonville juke joint, and he vanished from the Delta, not heard from again for an entire year.

One evening, as House and Brown performed at a gig in Banks, Mississippi, Johnson walked in with a guitar case slung over his shoulder. House nudged Brown and gestured sarcastically at 'Little Robert.'

"Boy, where are you headed with that thing?" House teased Johnson. "Planning to annoy everyone again?"

This time, however, things had changed. Johnson pulled out his guitar, a standard six-string but with an added seventh string, something neither House nor Brown had ever encountered. But that wasn't the only surprise.

Johnson had developed an extraordinary level of skill and a unique technique, playing rapid-fire chords that made the guitar mimic the sound of a piano — as if three hands were playing it at once.

How could this young man, who was once so unskilled that he was chased off the stage in Robinsonville, return just a year later as the most gifted blues guitarist in the Delta? To the astonished audience in Banks, Mississippi, there was only one possible explanation — Johnson had struck a pact with the devil.

Down at the Crossroads

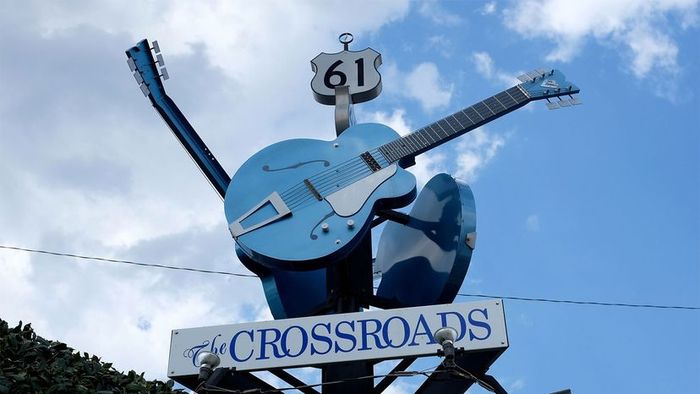

The intersection of Highways 61 and 49, where Robert Johnson is said to have traded his soul to the devil for musical brilliance, is marked by three blue guitars.

Peter Burka/Flckr/CC BY-SA 2.0

The intersection of Highways 61 and 49, where Robert Johnson is said to have traded his soul to the devil for musical brilliance, is marked by three blue guitars.

Peter Burka/Flckr/CC BY-SA 2.0For devout black communities in the 1920s Deep South, the blues was undeniably 'the devil's music.' It tempted decent people into juke joints, where they would dance, drink, and engage in sinful behavior. Thus, it seemed entirely plausible that Johnson's otherworldly talent was a gift from Satan.

Interestingly, Johnson wasn't the first blues artist rumored to have sharpened his craft with assistance from the Prince of Darkness. An earlier guitar legend named Tommy Johnson — no relation to Robert Johnson but hailing from the same Mississippi county — was said to have visited the crossroads and had his guitar tuned by the devil himself. (A biography of Tommy Johnson even includes an interview with his brother, who claims Tommy shared this tale firsthand.)

In the Coen brothers' film "O Brother, Where Art Thou?," a character named Tommy Johnson tells his companions that he recently traded his soul at the crossroads for extraordinary guitar skills.

"Oh son, you gave up your eternal soul for that?" asks the naive Delmar.

"Well," Tommy replies. "I wasn't using it."

When similar tales of soul-selling were told about Robert Johnson, he did nothing to deny them. In fact, he may have encouraged the sinister association. Among the 29 songs he recorded before his tragic death at 27, titles like "Cross Road Blues," "Hellhound on My Trail," "Me and the Devil Blues," and "Up Jumped the Devil" only fueled the myth.

The Real Education of Robert Johnson

Steven Johnson — a singer, preacher, and vice president of the Robert Johnson Blues Foundation — offers a much more grounded explanation for how his grandfather Robert went from a clumsy novice to a guitar virtuoso seemingly overnight, inspiring legendary musicians like Bob Dylan, Keith Richards, and Eric Clapton.

"I encourage people to look beyond the myth and appreciate the skill," Johnson explains in an interview. "Just because Michael Jordan was phenomenal on the basketball court, does that mean he sold his soul to the devil? No, he practiced relentlessly, far more than anyone else."

According to Steven, his grandfather's unexplained disappearance from the Delta music scene lasted nearly three years, not just one. During that time, he returned to his hometown of Hazelhurst, Mississippi, where he studied under the legendary guitarist Ike Zimmerman.

Robert had gone back to Hazelhurst in search of his biological father, Noah Johnson, but instead found Zimmerman. The two would venture to the local cemetery at midnight, where Zimmerman taught Johnson to play among the tombstones and the spirits of the departed.

"No matter how poorly you play out here," Zimmerman remarks in the Netflix documentary, "no one will complain."

The cemetery tale is likely fictional, but it contributed to Johnson's image as a tormented soul. In reality, his apprenticeship with Zimmerman was probably much more mundane. Steven Johnson recounts meeting Zimmerman's daughter, who was just a child when her father welcomed young Robert into their home.

"She told me, 'Your dad was at our house so often that I thought he was our brother,'" Steven recalls. "She asked her father, 'Is RL [what they called Robert] our brother?' 'No, he's not your brother,' Ike replied. 'He's just a musician and a good friend of mine.' He was always there."

The effort clearly paid off. In his recordings, Johnson was "playing a disjointed bass line on the lower strings, rhythm on the middle strings, and lead on the treble strings, all while singing," as Eric Clapton admiringly described in his autobiography, according to Vanity Fair. It sounded as if multiple musicians were playing at once. Johnson's fingerpicking technique became the blueprint for blues music.

What Really Happened at the Crossroads

Robert Johnson endured a difficult life. As a child, he was shuffled between homes and mistreated by his stepfather. As a young man, he married his beloved Virginia, who tragically died during childbirth along with their baby. Johnson experienced other loves and losses before becoming a full-time traveler, gaining a reputation as a heavy drinker and womanizer. It is believed that the husband of one of Johnson's lovers poisoned him, leading to his death at 27. Johnson remained relatively unknown until the re-release of his album "King of the Delta Blues Singers" in 1961.

When Steven Johnson listens to his grandfather's music, he doesn't hear the voice of a reckless sinner but rather a man striving to improve himself, burdened by painful memories, guilt, and pride. Even the song "Cross Road Blues," which some might interpret as a tale of Robert's encounter with the devil, holds a deeper meaning for Steven.

"I went to the crossroad, fell down on my knees," Johnson sings in his haunting, smooth voice. "Asked the Lord above, 'Have mercy, now save poor Bob, if you please.'"

"Does that sound like someone making a deal with the devil?" Steven asks. "He was at a crossroads in his life, seeking redemption and trying to do the right thing."

Learn more about Robert Johnson in "Crossroads: The Life and Afterlife of Blues Legend Robert Johnson" by Tom Graves. Mytour selects related titles based on books we believe you'll enjoy. If you choose to purchase one, we receive a portion of the sale.

Regardless of the legend's authenticity, enthusiastic visitors gather at Clarksdale, Mississippi, to snap photos at the intersection of Highway 61 and Highway 49. The only catch is that the actual crossroads during Johnson's time would have been half a mile away.