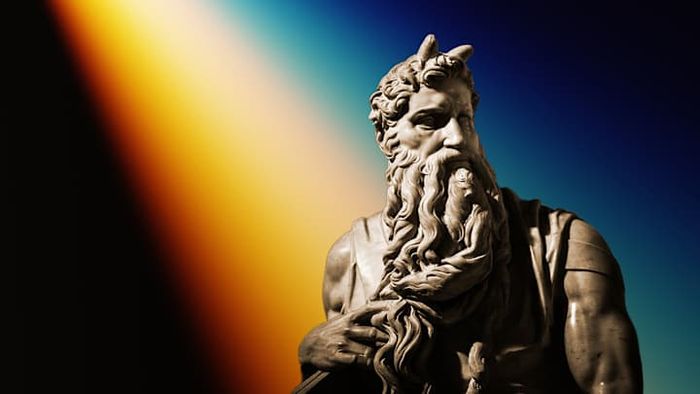

Michelangelo’s Moses shares an unexpected trait with C.S. Lewis’s Mr. Tumnus—small horns. Michelangelo wasn’t pioneering this portrayal; he was continuing a long-standing tradition rooted in a biblical passage.

However, the true meaning of this biblical description remains a topic of debate.

A Symbol of Moses’s Transformation

In Chapter 34 of the Old Testament’s Book of Exodus, Moses speaks with God on Mount Sinai to reestablish a broken covenant with the Israelites. Unaware, Moses’s appearance is altered by this divine encounter, causing the Israelites to fear and keep their distance as he descends with the Ten Commandments.

Scholars agree that Moses’s face (or its skin) underwent a transformation. However, the specifics are debated due to qāran, a rare Hebrew verb derived from qeren, meaning “horns.” While some translations suggest Moses’s face “was horned,” others interpret qāran metaphorically as “radiant” or similar.

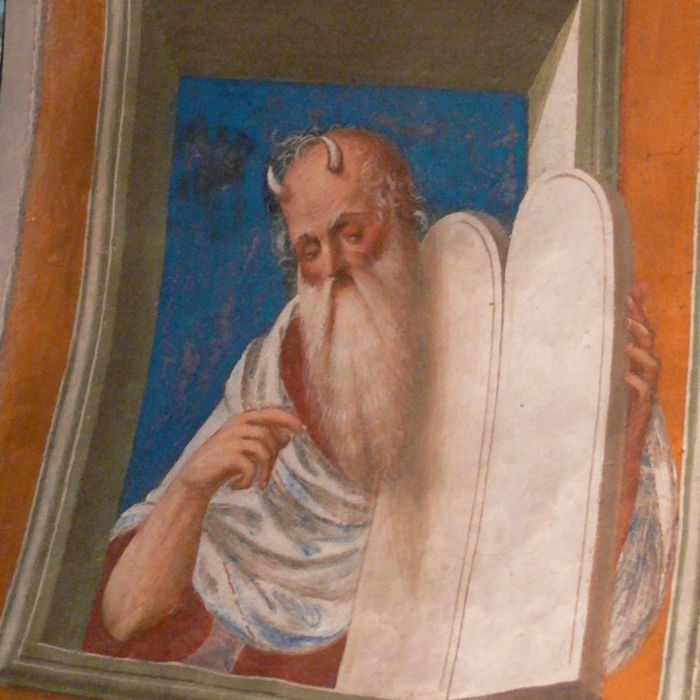

A fresco of a horned Moses at the Basilica di San Giulio in Italy. | Wolfgang Sauber, Wikimedia Commons // Public Domain

A fresco of a horned Moses at the Basilica di San Giulio in Italy. | Wolfgang Sauber, Wikimedia Commons // Public DomainThe Septuagint, the oldest Greek translation of the Hebrew Old Testament, describes Moses’s face as “glorified” or “charged with glory.” However, Saint Jerome’s Latin translation in the 4th and 5th centuries CE states, “cornuta esset facies sua,” meaning “his face was horned.”

Some speculate that Jerome might not have known qāran had an alternative (and arguably more fitting) meaning, leading to the potential mistranslation of horned. However, evidence suggests otherwise: In his writings on prophets, Jerome employs both glorified and horned to describe Moses’s transformation. He also notes that Aquila of Sinope chose horned in his Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible around the 2nd century BCE. While only fragments of Aquila’s work remain, scholars often refer to Jerome as the source for this claim. This makes it hard to confirm, but it shows Jerome’s use of horned wasn’t a careless error—he was aware of glorified as an option.

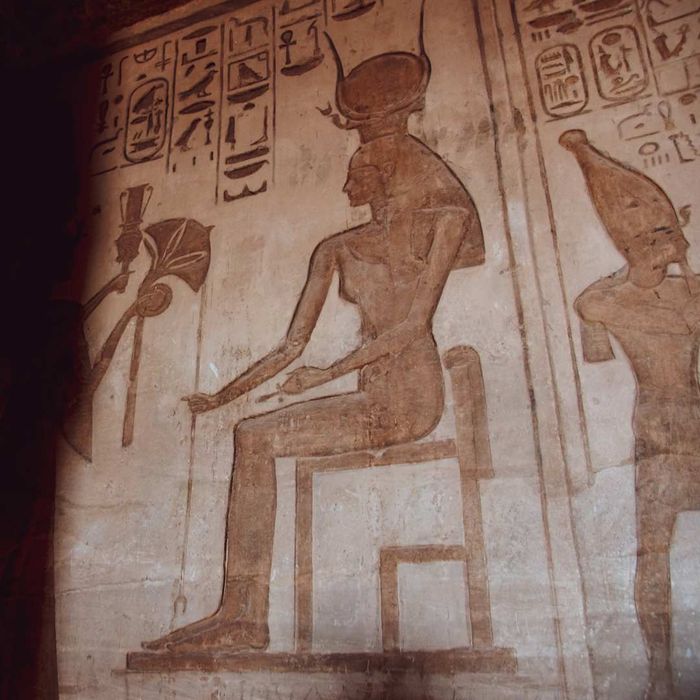

The Egyptian goddess Hathor, shown with her iconic horns and sun disk, in a temple dedicated to her and Queen Nefertari. | Lola L. Falantes/GettyImages

The Egyptian goddess Hathor, shown with her iconic horns and sun disk, in a temple dedicated to her and Queen Nefertari. | Lola L. Falantes/GettyImagesWhether Jerome meant horned literally is still debated. He might have: As Ruth Mellinkoff explained in her 1970 work The Horned Moses in Medieval Art and Thought, horns symbolized divinity, honor, and power across ancient civilizations. Deities from Mesopotamia to Scandinavia were often depicted with horns, and horns could “transfer divinity and power.” Mellinkoff suggested Jerome likely used horns metaphorically to signify Moses’s newfound power. Horns appear throughout the Bible as symbols of honor, strength, salvation, and other abstract concepts.

Why Not Both?

A 15th-century German illustration shows a horned Moses receiving the Ten Commandments. | Heritage Images/GettyImages

A 15th-century German illustration shows a horned Moses receiving the Ten Commandments. | Heritage Images/GettyImagesRegardless of interpretation, Jerome’s translation, known as the Vulgate, gained widespread popularity, inspiring others to depict Moses with horns. Notably, Aelfric’s 11th-century Old English Bible translation included illustrations of Moses with literal horns. As the Middle Ages transitioned into the Renaissance, many artists continued to portray the prophet with horns.

Many biblical scholars, however, preferred a symbolic interpretation. Some, like the 11th-century French rabbi Rashi, reconciled the two views by suggesting that horn-shaped rays of light emanated from Moses’s face or head—a depiction frequently seen in art throughout history.

A medieval statue of Moses located in Bruges, Belgium. | Fabio Canhim/GettyImages

A medieval statue of Moses located in Bruges, Belgium. | Fabio Canhim/GettyImagesModern Bible translations, such as the King James Version, the New American Standard Bible, and the English Standard Version, describe Moses’s face as “shining.” Similarly, the New International Version and the New Living Translation refer to it as “radiant.” This interpretation aligns more naturally with the original Hebrew text, which emphasizes the skin of Moses’s face, making the idea of it being “horned” seem unusual.

Today, horns are more commonly linked to devils than to divine figures, which could lead to misunderstandings about Moses’s depiction. Historically, antisemitic artists have used horns to vilify Jewish people. Some, like classicist Stephen Bertman, suggest Michelangelo’s horned Moses might have had similar intentions. However, as Old Testament scholar Brent A. Strawn notes on TheTorah.com, Michelangelo’s sculpture inspires awe rather than fear, suggesting any negative intent likely missed its mark.