Incas, the final captive Carolina parakeet in the U.S., passed away in 1918 at the Cincinnati Zoo, just months after his mate, Lady Jane. Despite the zoo's efforts spanning over 30 years to encourage breeding, the pair showed little interest in perpetuating their kind. They frequently discarded their eggs, resulting in no offspring.

By the time Incas died, sightings of wild Carolina parakeets had become scarce. Even seasoned ornithologists struggled to locate them in their final refuge, the wetlands of southern Florida. During a 1904 expedition to Okeechobee County, renowned bird expert Frank Michler Chapman observed merely a dozen. The last verified wild sighting occurred in 1920, though sporadic, unverified reports persisted into the 1940s. The species was formally declared extinct in 1939.

The sudden disappearance was unexpected. While habitat destruction and hunting had impacted the vibrant green parrots, their numbers in Florida seemed steady, with no indication of imminent extinction—until they abruptly vanished.

Over eight decades since their extinction declaration, researchers remain baffled by the sudden vanishing of these birds. Today, evolutionary biologists are employing advanced techniques to uncover the remaining clues and crack this enduring avian mystery.

An Ecological Mystery

Known as puzzi la née, or “head of yellow,” by the Seminole people, the Carolina parakeet was actually a petite parrot. These wild birds were frequently observed in America’s woodlands and meadows when European settlers first arrived, thriving across a vast expanse of the eastern U.S., stretching from the Midwest to the Atlantic Coast. Sightings were even recorded as far north as upstate New York.

‘The Carolina Parakeet’ by John James Audubon. | Heritage Images/GettyImages

‘The Carolina Parakeet’ by John James Audubon. | Heritage Images/GettyImagesThese birds were easily recognizable by their golden crowns and vibrant orange patches on their cheeks and foreheads. They typically moved in massive flocks of up to 300 individuals, favoring swampy riverine forests where they nested in the hollows of old trees. They also adapted well to farmlands. Similar to other parrots, Carolina parakeets had a diverse diet, consuming fruits, seeds, and grains. They were especially fond of cockleburs and were unaffected by the toxic compounds in the plant’s seeds.

Humans found the parakeets’ behavior troublesome. Large flocks could devastate apple orchards or cornfields, prompting farmers to shoot them on sight. Their tendency to gather around fallen flock members made them easy prey for armed landowners. Their friendly nature also made them desirable as pets, leading to widespread trapping for the pet trade.

Their vibrant feathers also worked against them. The Victorian-era trend of the plume boom fueled demand for feathers, wings, and even whole birds to decorate women’s hats. Carolina parakeets, along with herons and egrets, were heavily targeted by plume hunters.

The Weeks-McLean Act of 1913 banned the commercial hunting of migratory birds, effectively halting the plume trade in the U.S. [PDF]. (The Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918 further reinforced these protections.) While heron and egret populations gradually recovered, Carolina parakeets also seemed to bounce back.

Then, suddenly, they disappeared entirely.

Unraveling the Mystery

Other factors contributed to their decline. The parakeets’ natural habitat was quickly vanishing: Southern wetlands were drained for agriculture, and much of the eastern forests were cleared. They may have faced competition from honey bees for tree hollows, their preferred nesting sites. Additionally, their attraction to toxic cockleburs brought them closer to farms, where they could have been exposed to diseases spread by domestic poultry.

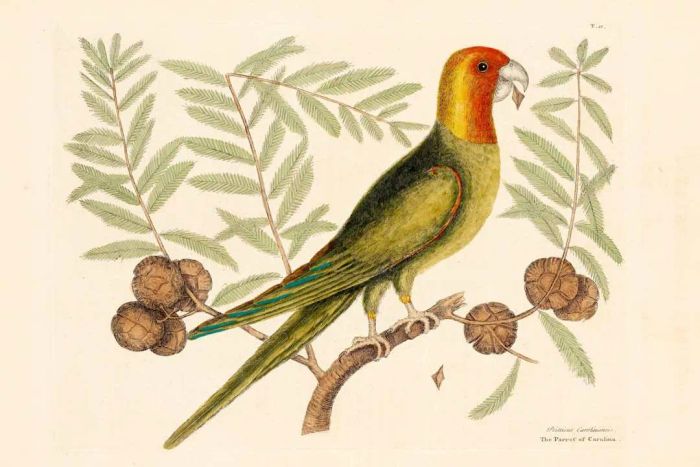

‘The Parrot of Carolina,’ by Mark Catesby, circa 1731-1743 | The Minnich Collection The Ethel Morrison Van Derlip Fund, 1966, Minneapolis Institute of Art // Public Domain

‘The Parrot of Carolina,’ by Mark Catesby, circa 1731-1743 | The Minnich Collection The Ethel Morrison Van Derlip Fund, 1966, Minneapolis Institute of Art // Public DomainAdding to the puzzle, over a dozen parrot species have gone extinct in the past two centuries—such as the Cuban macaw, the paradise parrot, and the Seychelles parakeet—but all were island dwellers. The Carolina parakeet, with its broader and more varied range, stands as the sole exception.

Recent research has eliminated some potential causes. A 2020 study published in Current Biology involved a team of evolutionary biologists and paleogeneticists analyzing the genome of the Carolina parakeet, using DNA extracted from a museum specimen in Spain. They discovered no evidence of inbreeding and minimal genetic markers suggesting the species was on the brink of extinction.

Dr. Kevin Burgio, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Massachusetts’s Northeast Climate Adaptation Science Center, dedicated over six years to examining historical records of Carolina parakeet sightings, some dating back to the 1500s. By mapping these accounts, he gained insights into the true extent of the parakeet’s habitat. His findings indicate the existence of two distinct subspecies: one in the Midwest, ranging south to Texas and Louisiana, and another in the East, spanning from Florida to Virginia.

This discovery could be pivotal. Burgio’s research suggests the Midwestern subspecies vanished by 1914, roughly three decades before the Eastern subspecies was declared extinct.

“During the 1800s to 1900s, the U.S. experienced a dramatic agricultural expansion,” Burgio explains to Mytour. “As farming spread, especially in the West, Carolina parakeet populations declined due to human proximity—whether through disease, hunting, or other factors.”

However, the exact cause remains elusive. “In my view, it’s likely a combination of factors—hunting, habitat destruction, and disease,” Burgio notes. “But pinpointing the primary cause is impossible, and we may never know for sure.”

Birds of Resurrection

Although the Carolina parakeet hasn’t been seen alive for over 100 years, a close living relative exists—the Sun parakeet, native to Brazil and Guyana. This endangered species shares a striking similarity with its extinct American counterpart and offers valuable genetic insights.

A 1930s depiction of a Carolina parakeet. At the time, they were nearing extinction. | “Articles About Birds from National Geographic Magazine,” Biodiversity Heritage Library // Public Domain

A 1930s depiction of a Carolina parakeet. At the time, they were nearing extinction. | “Articles About Birds from National Geographic Magazine,” Biodiversity Heritage Library // Public DomainWith the Carolina parakeet’s genome mapped and genetic material from Sun parakeets, scientists are inching closer to reviving the species through de-extinction. The Long Now Foundation’s Revive & Restore initiative is currently focused on bringing back the passenger pigeon, which vanished just decades before the parakeet. If successful, the parakeet could follow.

Not all scientists support the idea of reviving extinct species. Critics argue about the uncertainties of reintroducing creatures that have been absent for decades or even centuries, while proponents believe de-extinction could serve as a powerful conservation tool for endangered species today.

Understanding the Carolina parakeet’s extinction could offer crucial insights for protecting endangered species like the sun parakeet. Parrots are among the most threatened bird groups globally, primarily due to habitat destruction. Nearly one-third of all parrot species are at risk of extinction, and current protected areas are insufficient to safeguard them if deforestation persists, particularly in South America, Central America, and the Caribbean, where parrot diversity is greatest.

“Parrot-rich regions, especially in the Americas, are in rapidly developing countries undergoing transitions similar to the U.S. 150 years ago,” Burgio explains. “They face threats from human encroachment and habitat loss. It’s the same pattern repeating itself.” The decline of the Carolina parakeet aligns with America’s colonization and industrialization, and today, deforestation remains a major threat to wild parrots. The parakeet’s extinction serves as a stark reminder of how quickly a thriving species can vanish.

“If a parrot as widespread, charismatic, and beautiful as the Carolina parakeet can disappear,” Burgio says, “we must evaluate what we still have and work to protect it before it’s lost forever.”