On May 25, 1979, 6-year-old Etan Patz convinced his parents to let him walk to his school bus stop by himself. It was the final day before Memorial Day, and Patz insisted the stop was just two blocks away from their Lower Manhattan apartment. He mentioned he would grab a soda from a nearby deli before heading straight to the bus. His parents, aware of the short distance and their son’s reliability, eventually agreed.

On September 5, 1982, 12-year-old Johnny Gosch prepared his newspaper delivery bag in Des Moines, Iowa, and started his route. His dog, Gretchen, followed him as he made his rounds.

On August 12, 1984, Eugene Martin followed a similar routine, setting off on his paper route in Des Moines. The 13-year-old usually delivered papers with his stepbrother but chose to go alone that particular morning.

Patz never made it to school, and neither Gosch nor Martin came back after their delivery rounds. Gretchen, Gosch's dog, returned home alone.

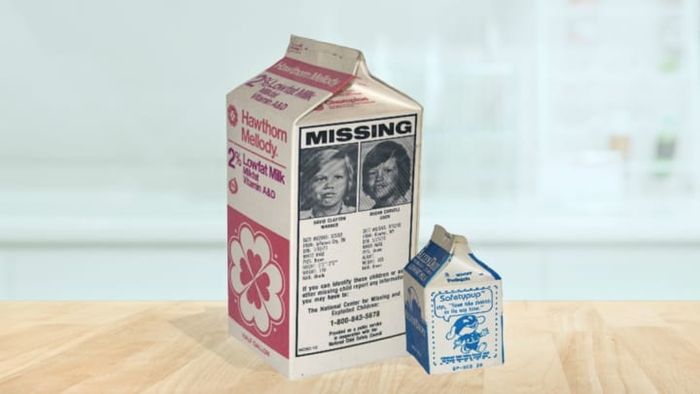

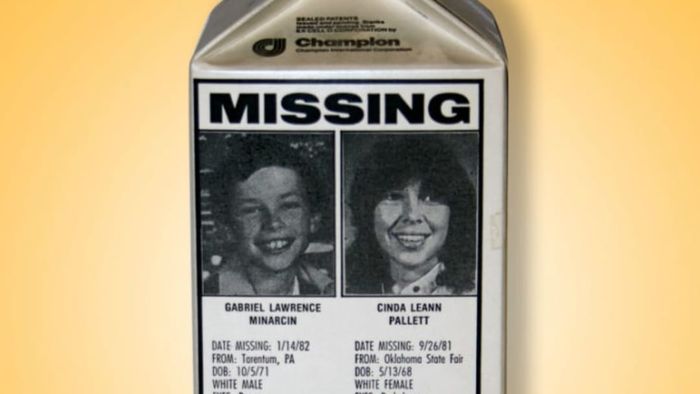

From late 1984 through early 1985, the faces of these three boys marked a unique moment in law enforcement history. They were among the earliest children to be displayed on milk cartons, which urged the public to assist in locating missing kids nationwide. Their images were printed on 3 to 5 billion dairy containers across the U.S., a massive pre-internet effort to spread awareness and gather leads. The media labeled them 'the milk carton kids,' cementing the image of missing children in black-and-white photos on cartons that became a fixture at breakfast tables across the country.

Despite the widespread presence of these images, their impact was debatable. Child advocates soon raised concerns—not just for the abducted children, but for the psychological effect on kids who were being taught that strangers were dangerous and that they, too, might end up as a statistic on a milk carton. Despite the good intentions of law enforcement, the milk carton campaign ended up frightening more children than it aided.

In the 1970s, a grassroots movement emerged to tackle the issue of noncustodial parents taking their children without legal consent. Frustrated by custody rulings or worried about the other parent's treatment, some parents would take their kids and move to another state. Law enforcement often viewed these cases as domestic disputes rather than crimes, and parents were frequently required to wait up to 72 hours before filing a police report.

The term 'child snatching' became common, and parent groups distributed pamphlets about missing children. Even when police cooperated, the slow process of faxing information between departments gave abducting parents ample time to vanish with their children before any alerts were issued.

Courtesy of National Child Safety Council

Courtesy of National Child Safety CouncilWhen Eugene Martin vanished in August 1984, public awareness efforts were still in their infancy. His disappearance, following that of Johnny Gosch, another Des Moines paperboy, brought significant attention to both cases. After discussions with the boys' parents and the Des Moines police chief, Anderson Erikson Dairy agreed to feature their photos on milk cartons in the Des Moines area starting September 1984. Prairie Farms Dairy soon joined the effort. This initiative spread to dairies in Wisconsin, Illinois, and California, with Chicago's launch in January 1985 capturing national media interest. By March 1985, 700 dairies were printing billions of cartons with images of missing children, even those from other states. For instance, Etan Patz's photo appeared on cartons in New Jersey and beyond, as abducted children were often transported across state lines.

The National Child Safety Council, a Michigan-based nonprofit, spearheaded the project. Its founder, H.R. Wilkinson, had observed the Des Moines campaign and played a key role in its expansion. The National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, a Department of Justice subdivision established by President Ronald Reagan, also contributed to improving child welfare. International Paper Company became a major participant, providing free printing plates for the photos, though the dairy industry incurred losses as the images replaced paid advertisements.

While milk cartons are the most iconic part of the campaign, missing-child photos appeared in numerous other places. Utility companies included inserts in bills, assuming most people would open them. In New York City, hot dog vendors displayed posters of missing children, and grocery bags also featured their images. Schools distributed single-serving milk cartons printed with safety tips from a mascot named Safetypup, aimed at educating children about stranger danger.

The campaign initially showed promise. In January 1985, 13-year-old Doria Paige Yarbrough, a runaway, saw her photo on a milk carton during a TV news segment in Fresno, California. Moved by the experience, she returned home to her mother in Lancaster. Similarly, in October 1985, 7-year-old Bonnie Bullock recognized her own face on a carton while eating cereal in Salida, Colorado. A friend informed her parents, who contacted the police. Bullock, who had been taken by her noncustodial mother from her father in Florida, was soon reunited with him.

While these cases garnered national attention, they also highlighted the slim chances of the photos leading to a successful resolution. Neither child had been taken by a stranger, a scenario far more likely to end in tragedy. Additionally, the public struggled to contextualize the statistics frequently cited in the media. Although 1.5 million children were reported missing annually—a figure from the Department of Health and Human Services—only 4,000 to 5,000 of these cases were genuine abductions. Over two-and-a-half years, the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children handled over 12,000 cases, yet only 393 involved stranger abductions.

No one disputed the importance of these cases, but some credible critics questioned whether milk cartons were the most effective way to address the issue.

By 1986, the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children reported that four children had been found due to their photos on milk cartons, a number that rose to six by 1987. However, given the billions of cartons in circulation, this success rate appeared minimal.

The Center later acknowledged that adults, who were more likely to recognize the children or contact authorities, largely ignored the cartons. Instead, children at breakfast tables were the ones scrutinizing the photos. Unable to identify anyone they knew, kids absorbed the fear that they, too, might become victims. While distributing photos helped locate over 100 children, placing them on milk cartons did not achieve the intended impact.

Photo illustration by Mytour. Milk Carton: Courtesy of the National Child Safety Council

Photo illustration by Mytour. Milk Carton: Courtesy of the National Child Safety CouncilBenjamin Spock, a celebrated pediatrician and author, criticized the campaign, arguing that its widespread use exposed children to the concept of criminal behavior before they were emotionally equipped to process it. The American Academy of Pediatrics supported his views. The idea of 'stranger danger,' which caused widespread fear among parents and children, was statistically disproportionate to the actual risk of abduction. Although tips were received, they seldom provided useful information for solving cases.

Noreen Gosch, Johnny’s mother, told the Associated Press, 'What it did was raise awareness. It didn’t necessarily provide us with actionable tips or leads.'

Despite its limitations, the campaign played a vital role in raising awareness. While the milk cartons may not have directly led to the recovery of missing children, their impact as a deterrent—discouraging kids from running away or potential abductors from acting—cannot be quantified.

By 1987, dairies began replacing the photos with safety tips for children, marking the decline of the campaign. The growing use of plastic milk jugs also contributed to its end. By 1989, images of missing children had nearly vanished from breakfast tables. Advances in telecommunications during the 1990s, including the internet and Amber Alerts, rendered the milk carton method outdated.

The original 'milk carton kids'—Patz, Gosch, and Martin—and their families, who helped initiate the campaign, never saw direct benefits from it. Gosch and Martin remain missing, with no arrests made. In 2012, Pedro Hernandez, a store clerk in Patz’s neighborhood, confessed to his murder after his brother-in-law informed police of Hernandez’s admission. Hernandez was convicted in 2017 and sentenced to 25 years to life in prison.

Although Patz’s image no longer graces the millions of milk cartons it once did, his impact remains significant. In 1983, President Reagan designated May 25, the day of his disappearance, as National Missing Children’s Day.