What we consider enjoyable evolves over time. In one era, gathering ferns might be the pastime of choice, while in another, streaming endless cat videos takes precedence. Yet, amidst shifting cultural trends, one form of amusement remains timeless.

Board games have their roots in ancient Egypt, and even in our digital era, their popularity endures. In his book It's All a Game, released recently, Tristan Donovan explores the evolution of board games, from chess to Monopoly and Settlers of Catan. From his work, we’ve extracted the intriguing backstories of seven legendary games.

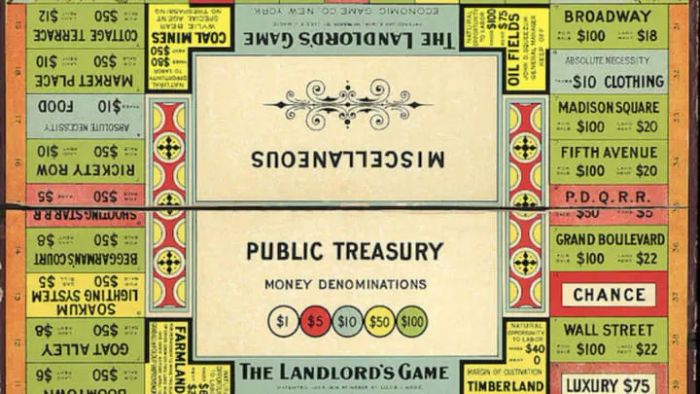

1. MONOPOLY

Many contemporary players view Monopoly as a celebration of ruthless capitalism. It faced bans in communist China and the Soviet Union, and Fidel Castro, after gaining power in Cuba, denounced it as a representation of an imperialistic and capitalist ideology. However, the game’s inventor had a vastly different message in mind.

Elizabeth “Lizzie” Magie was an ardent advocate of the single tax movement in the late 19th century. This proposal aimed to eliminate all taxes except for a single levy on property. By taxing landowners, the policy sought to reduce the disparity between affluent property owners and their working-class renters.

To make these ideas more engaging, Lizzie Magie transformed them into a board game in 1902. Initially titled The Landlord’s Game, the objective was to acquire as much property as possible. As properties became scarce and rents skyrocketed, landlords amassed wealth while other players faced financial ruin. The ultimate winner was the player who monopolized all the properties.

Magie believed her game’s critique of exploitative landlords was evident, but it eventually morphed into something far removed from her vision. After patenting it in 1904, she pitched it to Parker Brothers, who rejected it for being too politically charged. Despite this, the game gained a niche following, with enthusiasts creating their own modified versions. One such version, rebranded as Monopoly, caught Parker Brothers’ attention in 1934. This time, they agreed to publish it. However, they first had to resolve Magie’s original patent. She sold them the rights for $500, on the condition that her original Landlord’s Game would also be produced. It was clear which version resonated more with the public; the flashy, wealth-driven Monopoly became a hit, while Magie’s politically charged creation languished in obscurity.

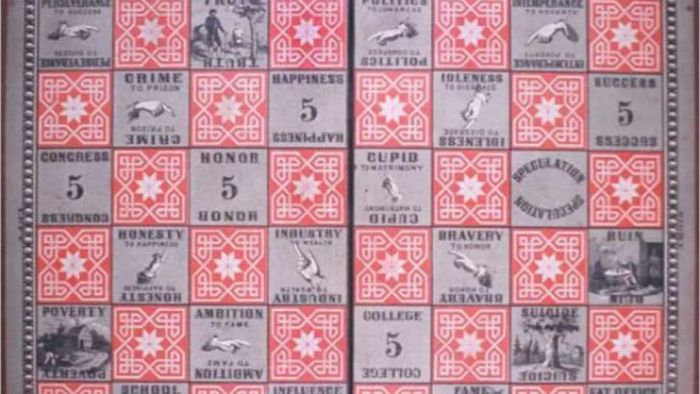

2. LIFE

Wikimedia Commons // Public Domain

Wikimedia Commons // Public Domain

By today’s standards, Life is a remarkably straightforward board game. However, when Milton Bradley introduced it in 1860, it was groundbreaking. Raised in a strict Protestant community in 19th-century New England, Bradley was taught that games were morally questionable. At 23, he sought to bridge this gap by creating a board game that doubled as a moral lesson. The outcome was The Checkered Game of Life, a cardboard-based guide to virtuous living. Players navigated life’s stages, earning or losing points based on their choices. Positive spaces like Honesty and Industry were rewarded, while negative ones, such as the controversial Suicide square, were avoided. Instead of dice, which were linked to gambling, players used a numbered “teetotum” to advance. The first to reach 100 points achieved “Happy Old Age.”

Despite its moral undertones, Bradley worried his game would be shunned by New England’s conservative audience. He opted to debut it in New York City, and his gamble paid off; hundreds of copies sold out within days. The Checkered Game of Life became a sensation, selling 40,000 copies in its debut year. After fading into obscurity by the century’s end, it was revived in 1959 as the more universally appealing Game of Life by the Milton Bradley Company.

3. CLUE

Wikimedia Commons // Fair Use

Wikimedia Commons // Fair UseDuring the early 1900s, Britain was enthralled by tales of crime. One of the most lasting contributions from the Golden Age of Detective Fiction wasn’t a book but a board game created by British couple Anthony and Elva Pratt. As detailed in It's All a Game, their design revolved around the same kind of rural estates that often featured in the era’s murder mysteries.

After removing some controversial aspects (the original title "Murder" was changed to Cluedo, and the gun room was swapped for a dining room extension), UK publisher Waddingtons acquired the rights in 1945. However, launching the game internationally proved difficult. While Parker Brothers president Robert Barton liked Cluedo, he initially rejected it due to a company policy against murder-themed products. Yet, the game lingered in his mind. Eventually, he persuaded the founder to bend the rule, leading to the U.S. release of Cluedo under the name Clue in 1949.

4. OPERATION

Marvin Glass, a renowned toy designer, pioneered the transition of board games into the plastic era. He made waves with Mouse Trap in 1963 and followed up with Operation two years later. However, the concept originated with John Spinello, an industrial design student at the University of Illinois.

For a school assignment, Spinello built a metal box featuring a winding groove with holes, through which users had to maneuver a metal probe. Touching the sides triggered a buzzer. Spinello pitched the idea to Marvin Glass through his godfather, who worked at Glass’s company. Glass purchased the invention and reimagined it as Operation, where players extracted plastic pieces like spare ribs and butterflies from a cartoon patient’s body using tweezers. The goal was to avoid touching the edges. Operation became a smash hit for Glass, while Spinello received only $500 and an unfulfilled promise of a job after graduation.

5. TWISTER

Had Twister been introduced a decade earlier, it might not have achieved its iconic status. However, its launch in the mid-1960s coincided with the sexual revolution, which challenged the conservative norms of earlier generations.

Reyn Guyer, a co-owner of a design agency, conceived the idea as a promotional giveaway for a client. Customers who submitted sufficient proofs of purchase would receive a complimentary gift. Guyer created a prototype called "King’s Footsie" on fiberboard to test its viability as a promotional item. Realizing its potential, he decided to pitch it as a standalone game. By the time he presented it to Milton Bradley, it had been rebranded as “Pretzel” and evolved to include players placing both hands and feet on a mat.

After renaming it Twister, Milton Bradley agreed to produce it—a gamble that nearly failed. Retailers hesitated to stock it, as the game’s physical interaction clashed with the family-friendly image many stores aimed to maintain. Just as Milton Bradley considered discontinuing it, an appearance on The Tonight Show changed everything. On May 3, 1966, Johnny Carson and guest Eva Gabor demonstrated the game live, captivating millions of viewers. Sales surged overnight. Despite some critics decrying its scandalous nature, shifting societal attitudes ensured Twister remained a staple for years to come.

6. TRIVIAL PURSUIT

Pratyeka, Wikimedia Commons // CC BY-SA 4.0

Pratyeka, Wikimedia Commons // CC BY-SA 4.0Before Trivial Pursuit came along, board games were often seen as childish or unrefined. While games like chess, backgammon, and Scrabble were deemed acceptable for adults, most board games weren’t considered suitable for social gatherings. As Tristan Donovan recounts in It's All a Game, this perception shifted in the early 1980s thanks to two Montreal-based friends, Chris Haney and Scott Abbott. Recognizing a gap in the market, they developed a game that challenged players with trivia questions spanning art, sports, history, and entertainment. They meticulously crafted questions such as “What is the first flavor in Life Savers candy?” and “How long did Yuri Gagarin spend in space?” After securing investors, they self-published the game. However, convincing retailers to stock a pricey, traditional-looking board game during the Atari craze was no easy feat. Despite initial hesitation, stores that took the chance saw Trivial Pursuit sell out rapidly. Demand soared, leading Selchow and Righter to acquire the rights in 1983. The game sold 20 million copies in its first year, proving that board games could appeal to adults and become a cultural phenomenon.

7. SETTLERS OF CATAN

Klaus Teuber had already made a name for himself in the board game industry before creating Settlers of Catan. He had won the prestigious Spiel des Jahres award three times, yet his earlier games didn’t generate enough sales for him to leave his job as a dental technician in Germany. Catan, however, changed everything. Inspired by his interest in Viking history, Teuber spent four years refining the game with his family before finalizing the iconic hexagonal tile design. Released in Germany in 1995, the game’s popularity didn’t wane—it grew, eventually reaching international markets and sparking a global interest in German-style board games. Unlike Monopoly, Catan offered simple rules, kept all players engaged, and could be completed in about an hour. While it wasn’t the first German game with these features, it was the first to bring this style of gameplay to a worldwide audience.

Craving more insights into board game history? Purchase It's All a Game here.