Crayons are synonymous with childhood memories. It's nearly impossible to picture growing up without their presence. Jennifer Smith/Getty Images

Crayons are synonymous with childhood memories. It's nearly impossible to picture growing up without their presence. Jennifer Smith/Getty ImagesDuncan is an ordinary child who enjoys creating art. He doodles, colors, and sketches without considering the impact on his tools — the simple crayon. However, the crayons have reached their limit. Fed up with being overlooked, these small wax and pigment sticks unite and decide to express their frustrations through a series of letters. While they don’t go as far as forming a union, their actions clearly represent a form of collective action, with each color detailing its unique grievances.

Red Crayon leads the charge, highlighting the exhaustion that comes with being Duncan’s preferred color. Purple Crayon complains about being used carelessly outside the lines, while Beige Crayon wishes it could be used for more than just turkeys and wheat. Gray Crayon, like Red, feels overburdened from coloring large animals like elephants and rhinos. White Crayon questions its purpose, Black Crayon is tired of being limited to outlines, Yellow and Orange argue over the sun’s true color, Blue Crayon is nearly worn down from coloring endless oceans, Pink Crayon feels stereotyped as a "girl’s color," and Peach Crayon simply wants its wrapper back. Only Green Crayon remains satisfied with its role.

This is the plot of the now-classic children's book, "The Day the Crayons Quit," authored by Drew Daywalt and Oliver Jeffers. Witty and endearing, the book underscores how crayons have become the quintessential medium for children's art. This connection is so deeply ingrained in our culture that it's hard to envision a time when kids didn’t have access to a vast spectrum of colors in a simple box of crayons. Yet, such a time did exist, and it wasn’t too distant in the past.

The Precursors to Crayons

The Conté crayon evolved from pastels (pictured here), which are created by blending pigment with chalk instead of wax. Alice Day/EyeEm/Getty Images

The Conté crayon evolved from pastels (pictured here), which are created by blending pigment with chalk instead of wax. Alice Day/EyeEm/Getty ImagesAt their core, crayons are simply colored wax sticks. Given their straightforward design, it’s easy to assume they’ve existed for centuries. However, the crayons we recognize today only emerged in the late 19th century. That said, the combination of wax and pigment has a rich and storied history in art and craftsmanship. Some even trace the crayon’s origins to the dawn of art, noting that Paleolithic artworks in France’s Lascaux caves were made using pigments mixed with animal fat, a substance similar to wax [source: Bell].

The exquisite art of batik boasts a long-standing tradition in Southeast Asia, particularly on the Indonesian island of Java. The term batik originates from Javanese, though its exact etymology remains unclear. Batik is a fabric dyeing technique where hot wax is applied to cloth in specific patterns. Once the wax hardens, the cloth is dyed, and the wax-covered areas resist the pigment. After drying, the wax is removed by reheating, revealing the intricate design [source: The Batik Guild].

The Batik Guild suggests that the technique of using wax to resist dye dates back at least 2,000 years. Evidence of its use has been found in ancient Egypt, China, India, and Africa. As far back as 2000 B.C.E., the ancient Greeks utilized beeswax to waterproof their ships. It was a logical progression to add pigments to the wax and use it to decorate these vessels [source: Bell].

A more direct ancestor of the crayon is the art form known as encaustic art. This method involves mixing beeswax with pigments, heating it until it becomes liquid or paste-like, and then applying it to a surface. This practice dates back to at least the first century C.E., when artists in Greco-Roman Egypt used it to create portraits of the deceased on their mummy caskets [source: Rankin].

During the late 1500s in Renaissance Italy, even the renowned Leonardo da Vinci experimented with a medium resembling crayons. He documented using wax-based colored sticks for drawing [source: Bell]. Ed Welter, a crayon expert and collector, confirmed that da Vinci crafted his own crayons.

"Almost everyone made their own crayons until the mid-1800s," Welter explains via email. "The ingredients varied widely and often included unsafe materials, as crayons were used for artistic, industrial, and commercial purposes." Welter also mentions that the Norwegian expressionist Edvard Munch created his own crayons in the late 1800s.

The 18th century saw a revival of interest in encaustic art, which has continued to grow since. Around the same time, the Conté crayon was developed in late 18th-century France [source: Welter]. Named after French scientist Nicolas-Jacques Conté, these crayons are derived from pastels but use clay and graphite instead of wax. Typically available in black, red, or brown, Conté crayons allowed artists to create works with handheld colored sticks that required no heating, cooling, or drying. This innovation brought us one step closer to the modern wax crayon.

The word "crayon" comes from the French word for "pencil," which itself derives from "craie" (meaning chalk, pronounced "cray"). The French term traces back to the Latin word "creta," also meaning chalk [source: Merriam-Webster].

Modern Crayons

Following the U.S. Civil War, several American companies entered the crayon industry. Charles A. Bowley, a manufacturer from Massachusetts, was the first to utilize paraffin, a new material for crayons. Garry Gay/Getty Images

Following the U.S. Civil War, several American companies entered the crayon industry. Charles A. Bowley, a manufacturer from Massachusetts, was the first to utilize paraffin, a new material for crayons. Garry Gay/Getty ImagesThe exact origin of the first wax crayon remains unclear, but Joseph Lemercier, a Parisian art supply maker, is a strong contender. His company began producing and selling colored wax crayons in the 1820s [source: Welter]. Shortly after, in 1835, the German firm J. S. Staedler introduced a wax crayon encased in wood. However, the wax was rigid and challenging to use [source: Bell]. Until then, all crayons were made with beeswax, which was costly and brittle. A breakthrough in materials was needed.

In the late 19th century, the bitumen coal mining industry in Eastern Europe produced a waxy byproduct called ceresin. This material was more affordable and pliable than beeswax. The Czech company Offenheim & Ziffer used ceresin to create a new type of crayon, which quickly gained acclaim for the lasting quality of its marks [source: Bell].

Following the U.S. Civil War, numerous American companies entered the crayon industry. Charles A. Bowley, a Massachusetts-based manufacturer, pioneered the use of paraffin, a material similar to ceresin. Derived from coal, paraffin remains the primary wax used in modern crayons. Bowley was also among the first to produce colored wax sticks in the familiar round, pencil-like shape we know today [source: Bell].

As Welter explains, the surge in crayon production after the Civil War was largely driven by the rapid industrialization of the late 19th century. Combined with the newfound availability of paraffin, these factors paved the way for the mass production of modern crayons.

Coincidentally, advancements in crayon manufacturing aligned with a growing focus on early childhood education. Crayons, being easy to store, handle, and use without the mess of paint or stains, were perfectly suited for children. As kindergartens spread nationwide, the enduring bond between kids and crayons was established.

A crucial factor in this connection was the development of non-toxic crayon production methods. "All crayons were toxic until the kindergarten movement of the 1880s," Welter notes. "A few high-profile documented cases of poisoning accelerated these changes. The availability of affordable paraffin wax, the demand for education in the industrial era, and the emphasis on art in schools all fueled the industry's growth."

Paraffin wax is heated until it liquefies, then blended with pigment and a strengthening agent. Pumps transfer the colored liquid into water-cooled steel molds, each containing 110 crayon-shaped cavities. Hydraulic pressure ejects the crayons from the molds, and a robotic arm transports them for labeling. The crayons are funneled, with one of each color dropped onto a platform and swept into boxes. Finally, a date code is laser-etched onto the box, and a metal detector ensures the contents are purely crayons.

Coloring with Crayons

Crayola reports that blue is the most beloved crayon color of all time. Michael H/Getty Images

Crayola reports that blue is the most beloved crayon color of all time. Michael H/Getty ImagesFor many, crayons evoke childhood memories and the innocence we associate with kids. However, even crayons can become a topic of political debate. In 2014, an Indian law student filed a lawsuit against a local manufacturer for labeling a pink crayon as "skin" [source: Reilly]. This is just one example of the controversies surrounding crayons and their colors.

For decades, Crayola produced a crayon named "flesh." The company claimed it represented the color of the human palm, which is similar across ethnicities [source: Boboltz]. However, studies in the 1960s revealed that children used it as the default skin tone in their drawings. By 1962, Crayola renamed the color "peach." Similarly, the crayon labeled "Indian red" was changed to "chestnut." While the name originally referred to a plant pigment from India, concerns arose that it might be misinterpreted as referencing the skin color of Native Americans [source: Davidson].

Other color changes have been less contentious. Early crayon colors were borrowed from artists' paint palettes. Many of Crayola's original hues, such as "raw umber," "cobalt blue," and "Venetian red," have been phased out to introduce new shades. Crayola has focused on creating innovative colors to replace them. The most recent color to be retired was "dandelion" in March of 2017, marking only the third time the company has removed colors from its lineup and the first time from its 24-crayon box.

Welter notes that Crayola launched "gold," "silver," and "copper" in 1903 but didn’t expand their metallic range until the 1980s. Since then, they’ve focused on introducing a variety of new colors. Welter has cataloged 331 unique shades, though Crayola has occasionally reused the same color under different names within the same box [source: Boboltz].

Beginning in the early 1990s, Crayola started involving fans in naming new colors [source: Boboltz]. Some standout examples include "Macaroni and Cheese," "Tickle Me Pink," and "Purple Mountain's Majesty."

According to Crayola, the world’s most renowned crayon maker, blue is the all-time favorite crayon color. It’s followed by red, violet, green, carnation pink, black, turquoise blue, blue green, periwinkle, and magenta.

The Future of Crayons

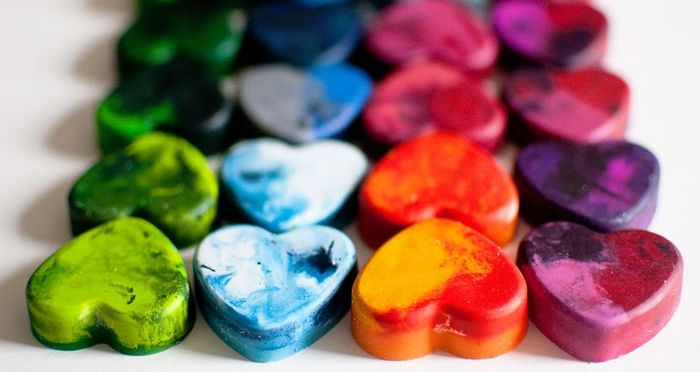

You can create custom crayons by melting down old crayon stubs and pouring the wax into heat-resistant molds to form fun, unique shapes. Lisa Gutierrez/Getty Images

You can create custom crayons by melting down old crayon stubs and pouring the wax into heat-resistant molds to form fun, unique shapes. Lisa Gutierrez/Getty ImagesIt might appear that the potential for reinventing crayons has been fully tapped. At this stage, crayons are what they are, and that’s unlikely to change. However, human creativity knows no bounds. The introduction of metallic hues in 1903 was groundbreaking. More recently, neon and even glow-in-the-dark crayons have entered the market. Undoubtedly, crayon manufacturers’ R&D teams will continue experimenting and launching innovative products.

Beyond the classic crayons designed for children, there are specialized crayons for adult artists that are softer and richer in pigment. Additionally, water-soluble crayons are available for both kids and adults. After coloring, a damp paintbrush can blend and spread the pigment, offering a unique artistic effect. This practice might hint at the future of crayons, where the most exciting advancements could emerge outside traditional manufacturing labs.

Parents are all too familiar with the scattered remnants of broken or worn-down crayon stubs around the house. While these tiny wax pieces are often too small to use, they can be given new life. Start by removing any remaining paper wrappers, then place the stubs in a heat-resistant container and melt them in a low-heat oven. The result is a vibrant, multi-colored crayon with a rainbow effect. For added creativity, use heat-resistant molds to shape the melted wax into unique forms.

To bring the concept full circle, take inspiration from batik art to create striking paintings. Begin by drawing a design with crayons on paper, then apply watercolors over it. The wax from the crayons will resist the paint, producing a luminous, mixed-media effect.

Crayons can transcend their traditional use and become art themselves. California artist Hoang Tran crafts intricate miniature sculptures by carving directly into individual crayons [source: DesignSwan].