Imagine a young woman who always wears a green ribbon around her neck. No matter how often her partner asks, she refuses to take it off or explain its significance. It isn’t until her final moments, as an elderly woman on her deathbed, that she allows him to undo the ribbon.

In an instant, her head tumbles to the ground.

Often referred to as “the girl with the green ribbon,” this tale is a cornerstone of Millennial urban legends, shared among friends at sleepovers and playgrounds during the late 1980s and later. While many mistakenly associate it with Alvin Schwartz’s Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark, it actually originates from his other collection, In a Dark, Dark Room and Other Stories, released in 1984 and aimed at younger audiences. (The official title is “The Green Ribbon,” and the protagonist is named Jenny.)

Although Schwartz was the first to dress his main character in green, he didn’t invent the idea of a headless woman concealing her condition with an accessory. Compared to earlier versions of such stories—which include themes like necrophilia, insanity, infidelity, demons, and the guillotine—“The Green Ribbon” is relatively tame and suitable for children.

The Devil Adorns Neckwear

In 1824, four years after “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” was published, Washington Irving released “The Adventure of the German Student” in his collection *Tales of a Traveller*. The story follows Gottfried Wolfgang, a student who travels to France hoping a new environment will heal his mental collapse, caused by excessive isolation and study. Unfortunately, Wolfgang continues his solitary habits in Paris, where the French Revolution is raging. He becomes consumed by dark literature, described as a “literary ghoul” who loses himself in his own imagination.

On a stormy night, Wolfgang encounters an eerily pale yet stunning woman sitting near the guillotine. She wears a black outfit with a diamond-clasped black band around her neck. He takes her to his apartment, where they vow eternal devotion. However, when Wolfgang returns the next morning after searching for a bigger place, he discovers his lover is dead. The police reveal she had been executed by guillotine the day before.

“The officer removed the black collar from the corpse’s neck, and the head fell to the floor!” Irving wrote. “They attempted to calm Wolfgang, but it was useless. He became convinced that an evil spirit had reanimated the corpse to trap him. He lost his mind and eventually died in an asylum.”

An elegant woman from the French Revolution period, whose head may or may not be fully attached. | (Woman) duncan1890/DigitalVision Vectors/Getty Images; (Diamonds) ilbusca/DigitalVision Vectors/Getty Images

An elegant woman from the French Revolution period, whose head may or may not be fully attached. | (Woman) duncan1890/DigitalVision Vectors/Getty Images; (Diamonds) ilbusca/DigitalVision Vectors/Getty ImagesIrving’s tale originated from a story shared with him in June 1824 by Irish author Thomas Moore, who had heard it from Horace Smith, an English writer. Moore told Irving that he believed the story would fit well into his collection of ghost stories, though he noted that Smith had already expressed interest in using it himself and likely had done so.

Moore was correct. In January 1823, Smith had released “Sir Guy Eveling’s Dream,” which parallels Irving’s “Adventure” but with notable variations. The story is set in London instead of Paris, and the protagonist is an English gentleman whose reckless behavior tarnishes his family’s reputation. He encounters a stunning woman who refuses to let him remove her elaborate neckwear, including a jeweled velvet necklace. Like Irving’s tale, the woman is found dead after the protagonist leaves for a brief errand.

Authorities identify the woman as the mistress of an Italian ambassador, recently executed for his murder. When they remove her necklace, they expose her bruised and discolored neck, marked by the harsh rope used in her hanging. Sir Guy, much like Wolfgang, descends into madness, convinced a demon had revived the corpse, and dies shortly after in a hospital.

A Scent of Guillotine in the Air

Smith’s “Sir Guy Eveling’s Dream” may have been influenced by a 1613 French pamphlet, which, as French-literature historian Maria Beliaeva Solomon noted in a 2022 article in *French Forum*, tells of a man’s moral downfall after unknowingly engaging in necrophilia with a woman executed and revived by the devil to deceive him. This woman, too, had been hanged.

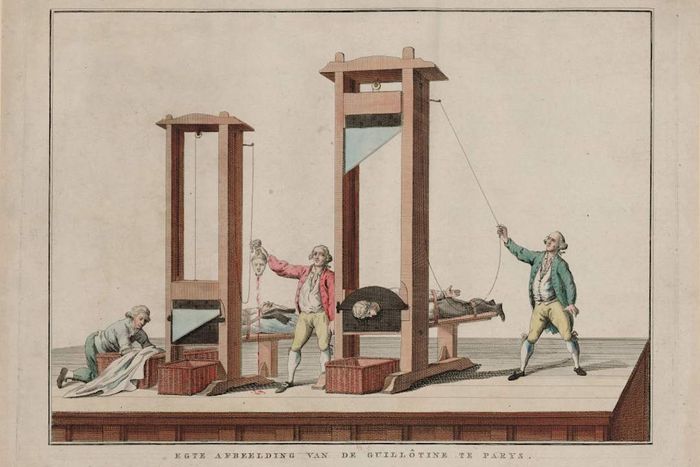

An 18th-century illustration of the guillotine in Paris, from the Collection of Bibliothèque Nationale de France. | Heritage Images/GettyImages

An 18th-century illustration of the guillotine in Paris, from the Collection of Bibliothèque Nationale de France. | Heritage Images/GettyImagesThe shadow of the Reign of Terror loomed large over 19th-century literature, and Irving’s choice to focus his story on the guillotine resonated widely. Variations of his narrative emerged in France during the mid-1800s, most notably in Alexandre Dumas’s 1849 novella *La Femme au collier de velours*, or *The Woman With the Velvet Necklace*.

Dumas anchored his rendition more firmly in historical context than his predecessors, even modeling some characters after real individuals and naming them accordingly. His German protagonist is Ernst Theodor Wilhelm Hoffmann, a Gothic horror author renowned for inspiring Tchaikovsky’s *The Nutcracker*. While the guillotined ballerina, Arsène, is fictional, Dumas portrays her as the mistress of the actual revolutionary figure Georges Danton.

The storyline largely follows Irving’s framework: A German man arrives in Paris during the French Revolution, encounters a captivating woman near the guillotine, and, after a night of passion, discovers her head is held on only by a black necklace. However, Dumas’s take leans less toward a supernatural ghost story and more toward a blend of historical romance and psychological suspense. Hoffmann betrays his fiancée back home, and Arsène’s decapitation isn’t the story’s final shock. (We’ll avoid spoiling the ending.)

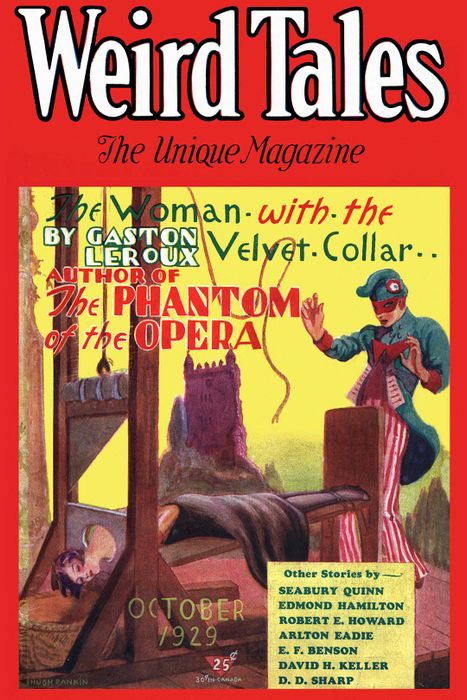

The *Weird Tales* cover, illustrated by Hugh Rankin, showcasing Leroux’s story. | ‘Weird Tales,’ Wikimedia Commons // Public Domain

The *Weird Tales* cover, illustrated by Hugh Rankin, showcasing Leroux’s story. | ‘Weird Tales,’ Wikimedia Commons // Public DomainDumas wasn’t the final prominent French author to explore the guillotined-woman theme. In 1924, Gaston Leroux—famous for *The Phantom of the Opera*—adopted Dumas’s exact title for his own narrative. In it, a retired French sea captain shares a chilling local legend he heard during his time in Corsica three decades prior.

In the story, the mayor hosts a costume ball themed around the French Revolution. His wife, the beautiful yet unfaithful Angeluccia, dresses as Marie Antoinette for a mock demonstration of her husband’s restored guillotine. However, the mayor knows of her affair, and the blade that descends on her neck is anything but fake.

Although Angeluccia survives the assassination attempt, guests later claim they witnessed her head completely separate from her body—hinting that the black velvet necklace she now wears might be hiding more than just a scar. The climactic moment arrives when her necklace is removed, but we’ll avoid revealing the outcome.

Decapitation Remains a Theme

Schwartz’s story of Jenny and her green ribbon is a stark departure from the dramatic tales that came before it. However, as Book Riot notes, there were earlier versions of this streamlined narrative: Ann McGovern’s “The Velvet Ribbon” from *Ghostly Fun* (1970) and Judith Bauer Stamper’s “The Black Velvet Ribbon” from *Tales for the Midnight Hour* (1977).

Both stories follow a similar plot. A man marries a woman who adamantly refuses to remove the black velvet ribbon around her neck, warning him, “You’ll regret it if I do.” Eventually, the man becomes so frustrated that he cuts the ribbon while she sleeps, causing her head to tumble to the floor.

Both works, released during the second wave of feminism, explore themes central to the era: consent, bodily autonomy, and the peril posed by a man—even a spouse—who refuses to accept rejection. The French Revolution-era stories also carry significant sociopolitical undertones, serving as warnings against allowing idealized fantasies to overshadow real-world horrors.

In contrast, “The Green Ribbon” is straightforward and can be interpreted literally, offering a relatively positive conclusion for this genre. Jenny discloses her secret on her own terms, only in her final moments. Additionally, the story is told from Jenny’s viewpoint, establishing her as the central character.

The story’s simplicity, combined with the widespread popularity of Schwartz’s books in the late 20th century, likely contributed to its status as the most iconic example of its microgenre. At fewer than 200 words, it can be summarized in just a few sentences. While “The Green Ribbon” may not delve into the complexities of its predecessors, echoes of those themes persist in modern interpretations. For instance, Carmen Maria Machado expanded on the ideas introduced by McGovern and Bauer Stamper in “The Husband Stitch,” from her 2017 collection *Her Body and Other Parties*. Similarly, Emily Carroll’s “A Lady’s Hands Are Cold,” from her 2014 graphic collection *Through the Woods*, embodies the essence of classic Gothic horror.

Beyond published works, the enduring cultural impact of the girl with the green ribbon is evident in the proliferation of memes inspired by her story.