In 1994, Tom Baccei and Cheri Smith, the minds behind Magic Eye, hosted General Mills executives at their N.E. Thing Enterprises office. Baccei showcased a prototype cereal ad featuring a bowl of cereal surrounded by a vibrant, seemingly random pattern. As the executives relaxed their gaze, the hidden message within the bowl became clear: BUY ME.

“Oh no, that’s not something we can do,” one executive remarked.

Baccei found the reaction amusing. By then, their company had already achieved remarkable success without resorting to subliminal tactics. Products featuring the immensely popular Magic Eye illustrations—initially appearing as flat, abstract designs before revealing stunning 3D visuals—were on track to generate $100 million in sales. Three of their Magic Eye books had secured spots on the New York Times bestseller list. The optical phenomenon adorned posters, mugs, greeting cards, games, and postcards, with plans to appear on Apple Cinnamon Cheerios boxes. Baccei and Smith had undeniably sparked a global 3D craze.

The Magic Eye 3D illusions were rooted in principles dating back to 1828, when Sir Charles Wheatstone, an English physicist, developed the stereoscope, a device that combined two images to produce a sense of depth. This innovation delighted figures like Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. In 1959, cognitive psychologist Béla Julesz advanced this idea by crafting the first black-and-white random-dot stereogram, making depth perception achievable without special tools. Julesz designed one image with randomly placed dots and slightly shifted a circular section in a second image. When viewed together, the circle seemed to hover, demonstrating that depth perception originates in the brain, not the eyes.

The stereopsis, or 3D effect, occurs because the brain merges two images to prevent double vision. In the 1970s, visual neuroscientist Christopher Tyler and programmer Maureen Clarke refined the concept into a single-image autostereogram. However, it was Baccei and Smith who transformed this visual trick into a cultural sensation, enhancing autostereograms by embedding intricate 3D shapes within vibrant designs.

During the 1970s, Baccei worked as a bus driver for Green Tortoise, a so-called “hippie” transport service. Later, he joined Pentica Systems, a computer hardware firm near Boston, Massachusetts. At Pentica, Baccei was responsible for promoting a MIME in-circuit emulator, a tool for debugging computers. Naturally, he hired a mime for the advertisement.

The mime, Ron Labbe, was passionate about 3D photography and brought a stereo camera to the shoot. When Baccei inquired about learning more, Labbe recommended Stereo World magazine. There, Baccei encountered a single-image random-dot stereogram, fascinated by how what looked like static could reveal hidden shapes when viewed correctly.

Inspired, Baccei created a stereogram for Pentica that concealed a product’s model number within the image, offering a prize to anyone who could decipher it. The ad became a hit, with readers tearing it out of magazines, displaying it in offices, and sharing it via fax.

Baccei showed Smith, a celebrated computer artist and animator with a passion for 3D photography, a stereogram from Stereo World magazine. While Baccei had been referring to his experiments as “Gaze Toys,” Smith envisioned the possibility of crafting vibrant artwork and rebranding the concept with a more marketable name. Together, they began developing intricate 3D illusions using advanced computers, moving beyond the basic clip art Baccei had previously used.

Bob Salitsky, a colleague at Pentica, enhanced the dot patterns to produce clearer images, a breakthrough that was later patented. For instance, viewing a tropical fish image would reveal a fish tank. By 1991, Baccei and Smith were building a startup focused on 3D illusions under Baccei’s N.E. Thing Enterprises, taking on projects for various clients. One of their illusions appeared in American Way, American Airlines’ magazine, catching the attention of a Tenyo Co. Limited executive from Japan. This led to collaborations with Tenyo on books and other products.

Tenyo, a well-known distributor of magic-related items, proposed naming the new 3D products “Magic Eyes” to be sold alongside their existing magic products. The Magic Eyes line quickly became a sensation in Japan. However, since “Magic Eyes” was too generic to trademark in the U.S., the name was shortened to “Magic Eye.”

The in-flight magazine image also drew the interest of Mark Gregorek, a licensing agent who approached Baccei and Smith. Recognizing the immense potential for partnerships, Gregorek secured a deal with Andrews McMeel Publishing in 1993, earning him the role of their U.S. licensing agent. Magic Eye was poised for success in America, though no one could have predicted the scale of what was to come.

The initial print run of 30,000 copies of Magic Eye: A New Way of Looking at the World (also known as Magic Eye I) sold out quickly, prompting Andrews McMeel to distribute 500,000 more. Magic Eye I, Magic Eye II, and Magic Eye III became bestsellers, spending a combined 73 weeks on the New York Times Bestseller List. N.E. Thing Enterprises, which rebranded as Magic Eye Inc. in 1996, struck deals for postcards, posters, a comic strip, and 20 million cereal boxes. Mall kiosks, initially launched by competitor NVision Grafix, sold Magic Eye posters, creating a social phenomenon as groups of people tried to decipher the hidden images. Those struggling to see the 3D effect were advised to place their nose close to the poster and slowly move back, revealing the illusion. Magic Eye and NVision posters became a cultural obsession.

As earnings soared beyond $100 million, Baccei realized the public’s fascination wouldn’t last indefinitely. Similar to trends like the Pet Rock and the Hula Hoop, consumer interest would eventually wane. Additionally, cheap imitations of Magic Eye posters began flooding the market, selling for under $5, while authentic Magic Eye or NVision posters retailed for $25.

By 1995, as poster sales dwindled, Baccei sold his stake in Magic Eye to his partner Smith and artist Andy Paraskevas. The company rebranded as Magic Eye Inc., consolidating sales and licensing operations internally.

The new leadership at Magic Eye shifted their focus to diversifying their product range. They collaborated with Warner Bros. Consumer Products to release Magic Eye: The Amazing Spider-Man, alongside other offerings like jigsaw puzzles, Valentine’s Day sets, wall calendars, and a syndicated weekly Magic Eye feature.

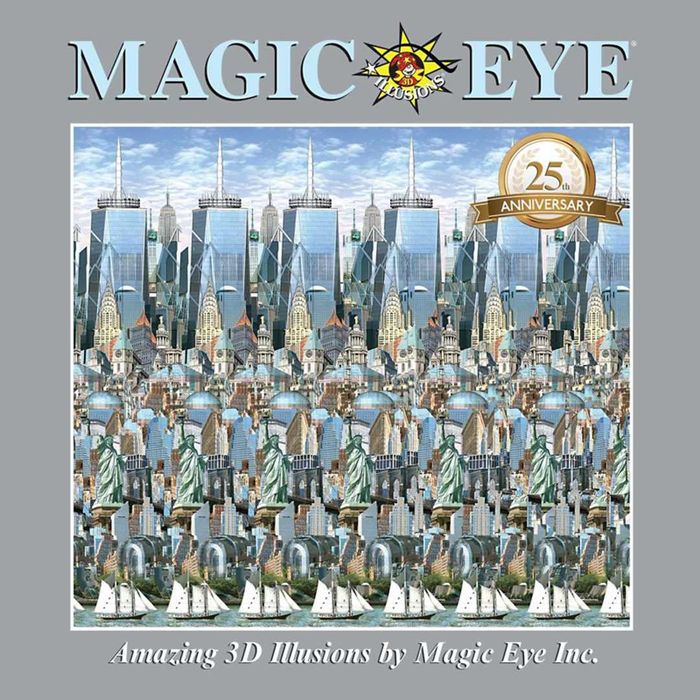

The Magic Eye 25th Anniversary Book. | © Magic Eye Inc

The Magic Eye 25th Anniversary Book. | © Magic Eye IncIn 1999, Paraskevas sold his share of the company to Smith, who partnered with Tenyo to produce a Magic Eye book called Miru Miru Magu Yokunaru Magic Eye. The book emphasized using Magic Eye 3D illusions for vision enhancement and became a hit in Japan once again. A follow-up vision improvement book was also published. Smith later collaborated with Warner Bros. to develop four Harry Potter-themed Magic Eye books and related merchandise. She also introduced a U.S. edition of a vision improvement book, Magic Eye Beyond 3D: Improve Your Vision, co-authored with optometrist Marc Grossman, featuring health insights from various experts and Magic Eye exercises.

Today, Smith remains active in creating books, maintaining the weekly Magic Eye syndicated feature, and developing new products, including using Magic Eye 3D illusions for advertising. Her latest works include The Magic Eye 25th Anniversary Book and Magic Eye: Have Fun in 3D, with plans to release another book in 2025.

You can explore Magic Eye illusions on their official website and Facebook page.