In June 1906, Danish adventurer Ludvig Mylius-Erichsen headed a 28-man team to northeast Greenland to map its unexplored regions. While the Denmark Expedition gathered valuable data, the mission was marred by tragedy when Mylius-Erichsen, cartographer Niels Peter Høeg-Hagen, and Inuit dogsledder Jørgen Brønlund vanished during a sled journey to Danmark Fjord.

In March 1908, the remaining explorers found Brønlund’s body, along with his diary and sketch maps. His final entry detailed his struggle with frostbite and his eventual demise in November, revealing that his companions had perished earlier that month. Though he provided clues to their location, their bodies were never recovered before the team returned to Denmark.

Mylius-Erichsen (left) alongside fellow members of the 1906 Denmark expedition. | Det Kongelige Bibliotek, Wikimedia Commons // Public Domain

Mylius-Erichsen (left) alongside fellow members of the 1906 Denmark expedition. | Det Kongelige Bibliotek, Wikimedia Commons // Public DomainA rescue mission for those already lost might not have attracted much funding. However, recovering Mylius-Erichsen and Høeg-Hagen’s journals could answer critical questions about Greenland’s geography, particularly the existence of Peary Channel. American explorer Robert Peary, famous for his North Pole expeditions, claimed that northeast Greenland was divided by a waterway he named “Peary Channel.” If the missing Denmark Expedition records supported this, it could imply the land above the channel was U.S. territory, not Denmark’s.

In June 1909, Danish explorer Ejnar Mikkelsen, a close friend of Mylius-Erichsen, and six crew members embarked on a perilous journey to Greenland aboard the motorized sloop Alabama. Their mission was to uncover the truth, but they faced relentless Arctic challenges, including starvation, scurvy, frostbite, and polar bear attacks. Mikkelsen documented their ordeal in his memoir Two Against the Ice, which inspired Netflix’s film Against the Ice, co-written, co-produced, and starring Game of Thrones’ Nikolaj Coster-Waldau as Mikkelsen.

Discover the true story behind the film.

Iversen Steps Up to the Challenge

The Alabama near Shannon Island in September 1909. | Det Kongelige Bibliotek, Wikimedia Commons // Public Domain

The Alabama near Shannon Island in September 1909. | Det Kongelige Bibliotek, Wikimedia Commons // Public DomainThe expedition faced early setbacks. The sled dogs intended for the journey were diseased, forcing Mikkelsen and his team to euthanize them and stop in Angmagssalik (now Tasiilaq) to buy new ones from the Inuit. To make matters worse, the mechanic, Aagaard, fell severely ill and had to leave, leaving the malfunctioning Alabama motor in disrepair. Fortunately, the captain of the Icelandic ship Islands Falk received approval from the Danish Admiralty to loan an assistant mechanic to Mikkelsen for the duration of the expedition.

Only one person stepped forward for the role: Iver P. Iversen, a spirited young engineer with no Arctic background but a long-held dream of joining Mikkelsen’s crew after reading about the expedition in a magazine. After a day of noisy repairs—accompanied by Iversen’s cheerful singing and whistling—he emerged with a confident smile, declaring, “Well, skipper, just say the word, and the motor will run.”

Finally, the Alabama set sail for northeastern Greenland, arriving in late summer and anchoring safely off Shannon Island for the winter. Mikkelsen planned a sled journey to Lambert Land, 330 miles north, where Brønlund had perished. After Mikkelsen emphasized the dangers, Lieutenant C. H. Jørgensen volunteered, as did Iversen, who brushed off Mikkelsen’s warnings with a laugh.

Jørgensen’s Final Act of Bravery

Ejnar Mikkelsen photographed by Ernest de Koven Leffingwell during an expedition to Alaska in 1907. | U.S. Geological Survey Photographic Library, Wikimedia Commons // Public Domain

Ejnar Mikkelsen photographed by Ernest de Koven Leffingwell during an expedition to Alaska in 1907. | U.S. Geological Survey Photographic Library, Wikimedia Commons // Public DomainOn September 26, the trio left the Alabama with their dog sledges, navigating treacherous, thin ice that often revealed narwhals swimming beneath. “It was unsettling to see the ice so fragile,” Mikkelsen noted. What should have been a five-day journey took 16 grueling days, culminating at the Denmark Expedition’s former camp, Danmarkshavn, where they rested for four days. Pushing onward to Lambert Land, they lost two dogs to exhaustion and witnessed their last sunlight on October 25, marking the start of a long, dark winter.

Mikkelsen was the first to discover the burial site of Brønlund. With care, they removed the snow covering his remains, uncovering sketches of his companions and other personal items. After giving Brønlund a proper burial, they searched for Mylius-Erichsen and Høeg-Hagen. However, years of melting and refreezing ice had erased any trace of their bodies, leading them to conclude the sea had claimed their fallen comrades.

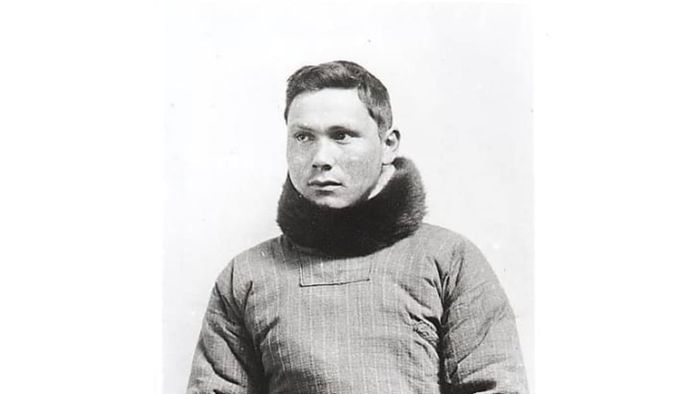

Jørgen Brønlund circa 1906. | Det Kongelige Bibliotek, Wikimedia Commons // Public Domain

Jørgen Brønlund circa 1906. | Det Kongelige Bibliotek, Wikimedia Commons // Public DomainThe trio began their arduous journey back to the Alabama, battling starvation and frostbite. The dogs, driven by hunger, turned on each other, while Jørgensen lost five toes to severe frostbite. Mikkelsen recalled that the amputation was performed with only half a bottle of whisky as anesthesia.

Jørgensen’s condition posed a new challenge. Mikkelsen had planned a spring expedition to Danmark Fjord to retrieve any records Mylius-Erichsen might have left in cairns. With Jørgensen unable to endure such a demanding trek, Mikkelsen needed a new companion. Before Mikkelsen could even raise the issue, Iversen once again stepped forward, offering to join him. Mikkelsen agreed.

“It can’t be much worse than the journey we’re nearly done with,” Iversen remarked. Reader, it was far worse.

“Solitude Amidst Dogs and Ice”

Mikkelsen and Iversen the day before setting off alone in April 1910. | Det Kongelige Bibliotek, Wikimedia Commons // Public Domain

Mikkelsen and Iversen the day before setting off alone in April 1910. | Det Kongelige Bibliotek, Wikimedia Commons // Public DomainUpon returning to Shannon Island, their companions welcomed them with steaming coffee and thick slices of buttered bread. Netflix’s Against the Ice opens with this scene, though the fictionalized Iversen, portrayed by Joe Cole, is shown with the crew rather than having ventured to Lambert Land.

In spring 1910, all except Jørgensen and Carl Unger journeyed inland, retracing Mylius-Erichsen’s path to Danmark Fjord. On April 10, Mikkelsen and Iversen parted ways with the group, who returned to the Alabama. Over the following weeks, the duo developed a rhythm, with Iversen singing improvised tunes (“Alone, alone, quite alone between Heaven and Earth / Alone with dogs and ice, alone, quite alone”) and quizzing Mikkelsen about polar exploration. Mikkelsen tolerated this—up to a point.

“Often, these inquisitive sessions ended with a brusque: ‘Oh, quiet down, Iver. Save your energy for helping the dogs pull,’” Mikkelsen recalled.

Coster-Waldau and Cole in Against the Ice. | Netflix/Lilja Jonsdottir

Coster-Waldau and Cole in Against the Ice. | Netflix/Lilja JonsdottirThey poured water onto their sledge runners, forming a slick layer of ice to boost their speed. They hunted musk-oxen whenever possible, though hunger was a constant companion. They endured frostbitten fingers, harsh winds, and the haunting “many-voiced specter” of fear during every quiet moment. On May 22, they discovered the first cairn, containing a letter from Mylius-Erichsen dated September 12, 1907, stating that the trio was healthy and had begun their return journey. Iversen and Mikkelsen pressed on for four more days, reaching a bleak, desolate site that had served as the group’s summer camp. Among several cairns, the last held a revealing letter from August 8, 1907.

“We … arrived at Peary’s Cape Glacier and confirmed that Peary Channel does not exist; Navy Cliff is connected to Heilprin Land by land,” Mylius-Erichsen wrote.

With their mission complete, Iversen and Mikkelsen steered their sledges back toward Shannon Island.

The Quest for Sustenance

Mikkelsen soon fell gravely ill with scurvy, suffering from “swollen joints, vivid skin patches, loose teeth, bleeding gums, and overwhelming weakness” that left him unable to walk, forcing him to ride atop the sledge. His condition improved after consuming a dozen barely cooked gulls, including their entrails, likely due to the vitamin C in raw meat. The desperate pair resorted to unconventional meals, such as moldy lumps from an old explorers’ cache, which Iversen considered “a form of vegetable.” “They didn’t sit well with us,” Mikkelsen noted.

Even their loyal sled dogs became a source of food. Uncertain if the livers were toxic, they used an old method: placing a silver locket in the cooking pot to test for poison. When the results were unclear, they took the risk and ate the livers. The meal left them severely ill, sleeping for 24 hours and waking with intense headaches and other ailments.

Danmarkshavn in 2013. | Andreas Faessler, Wikimedia Commons // CC BY-SA 3.0 DE

Danmarkshavn in 2013. | Andreas Faessler, Wikimedia Commons // CC BY-SA 3.0 DEAs they approached Danmarkshavn, they wrapped their remaining belongings—including diaries and Mylius-Erichsen’s letters—in a shirt and hid them in a rock crevice to lighten their load. They reached Danmarkshavn on September 18 and feasted on the Denmark Expedition’s leftover provisions, indulging in chocolate, porridge, stew, and sardine-topped biscuits. After a month-long break, they prepared to leave for the Alabama, now just 130 miles away.

However, Mikkelsen had instructed his crew to leave by August 15, with or without them. By now, it was well past that date.

An Unbreakable Bond

The exhausted pair hoped so intensely that the crew had ignored the orders that they convinced themselves it was true. Their belief seemed confirmed when they spotted the ship’s mast glowing in the moonlight. Yet, the silence puzzled them. Upon closer inspection, they discovered the mast was no longer attached to the ship, which had been dismantled to build a house. Unaware to Mikkelsen and Iversen, the Alabama had sustained damage and started sinking, prompting the crew to repurpose it into shelter. Rescued by a Norwegian ship in late July, the crew, seeing no trace of their companions by early August, departed with the Norwegians and were later picked up by a schooner on August 11.

Mikkelsen and Iversen had no option but to settle into the house for the harsh winter—which stretched into spring, then summer, until Norwegian sealers finally rescued them on July 19, 1912.

The film adaptation dramatizes this extended survival period, though it stays true to key events. The men did defend themselves against polar bears, and Mikkelsen treated a large boil on his neck himself (Iversen declined to help). While Mikkelsen later married Naja Holm—daughter of a fellow Danish explorer—in May 1913, he never mentioned hallucinating her in the Arctic, nor did he reference her in his expedition memoirs. Iversen, however, claimed to see his grandfather sitting near the hut, believing the old man had died—a fact he later confirmed.

Cole as Iversen in front of the Alabama house in Against the Ice. | Netflix/Lilja Jonsdottir

Cole as Iversen in front of the Alabama house in Against the Ice. | Netflix/Lilja JonsdottirAccording to Mikkelsen, he never experienced madness or violent impulses while living with Iversen. Their occasional disagreements were surprisingly civil. Once, while arguing over the rules of a new card game, Mikkelsen tossed the deck into the wind. “Iver looked displeased at first, but the next day he admitted my action was quite sensible,” Mikkelsen recalled.

Another memorable moment involved a postcard Iversen owned, featuring a group of young women in a schoolyard. They playfully named them—Miss Affectation, Miss Sulky, Miss Long, Miss Short, and so on—and each picked a favorite. Mikkelsen favored Miss Steadfast, “a lovely girl in a white dress with a carefree demeanor.” Iversen, however, was drawn to little Miss Sunbeam, “whose youthful, cheerful smile melted his nearly frozen heart.” (This touching story was what inspired Coster-Waldau to adapt the tale for the big screen.)

One morning, while preparing porridge, Iversen began singing a tune he’d made up about Miss Steadfast. He quickly noticed the pain in Mikkelsen’s expression, and the two spent the rest of the day in silence. The following morning, Iversen left Mikkelsen a note: “I’m sorry I took your girl. Take her back, take my four, take them all—just be cheerful again!” The pair laughed over the incident and shared their next meal “smiling at each other, grateful for their friendship.”

Finally, Homeward Bound

A sketch of Ejnar Mikkelsen by Beverly Bennett Dobbs, dated 1908. | Kapitän Mikkelsen: Ein arktischer Robinson, Wikimedia Commons // Public Domain

A sketch of Ejnar Mikkelsen by Beverly Bennett Dobbs, dated 1908. | Kapitän Mikkelsen: Ein arktischer Robinson, Wikimedia Commons // Public DomainMikkelsen and Iversen left Shannon Island a few times, including a February 1911 trip to recover their belongings from a rock crevice near Danmarkshavn. Unlike the film’s depiction, they found no rescue messages upon returning to the Alabama. However, a later journey to Bass Rock, about 30 miles away, brought crushing disappointment when they discovered notes from two ships that had searched for them. In April 1912, Mikkelsen carved his initials and the date into driftwood, a clue that led Norwegian sealers, spurred by a Danish government reward, to search Shannon Island in July.

“Hand over your rifles, boys, we come in peace,” declared Paul Lillenaes, the ship’s owner, as Mikkelsen and Iversen emerged armed, expecting a polar bear. Instead, they saw the first humans they’d met in almost 28 months.

Lillenaes brought them to Norway, where they were greeted with champagne, fresh clothes, and telegrams from family (including one from Denmark’s King Christian IX). Their return to Copenhagen sparked widespread celebration, with newspapers worldwide marveling at their miraculous survival.

“Half Naked and Like Frightened Arctic Animals, Explorers Are Found After Two Years’ Wandering,” The Vancouver Sun reported.

While their harrowing story captivated audiences globally, their homecoming may not have been as politically triumphant as Against the Ice implies. For instance, Mikkelsen never received the Royal Danish Geographical Society’s gold medal, likely due to his criticism of the Denmark Expedition. Additionally, though he is sometimes credited with disproving the existence of Peary Channel, the recognition typically goes to Knud Rasmussen, a Danish-Inuit explorer who witnessed the area firsthand in 1912—coinciding with Mikkelsen and Iversen’s rescue. (Rasmussen had also searched for the missing men during his expedition but found nothing.)

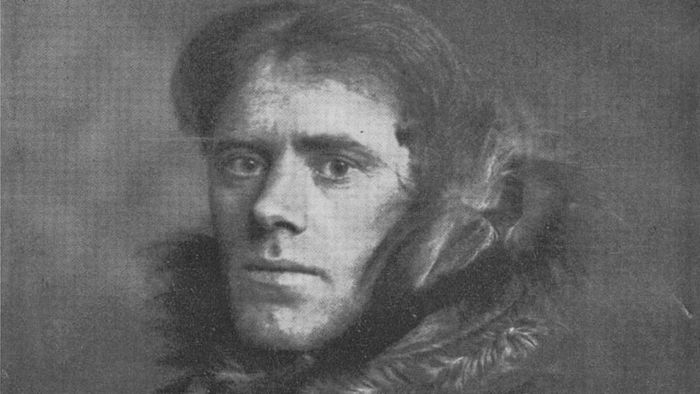

Knud Rasmussen, date unknown. | George Grantham Bain Collection, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Wikimedia Commons // No Known Restrictions on Publication

Knud Rasmussen, date unknown. | George Grantham Bain Collection, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Wikimedia Commons // No Known Restrictions on PublicationMikkelsen continued to make significant contributions to exploration. In 1924, he assisted Inuit in founding Ittoqqortoormiit, a village in east Greenland’s Scoresby Sound, and led a scientific survey of southeast Greenland in 1932. From 1934 until his retirement in 1950, he served as east Greenland’s inspector general, dedicating his efforts to establishing Inuit communities across the region.

Details about Iversen’s life after 1912 are scarce. In Two Against the Ice, Mikkelsen recalls speaking with him over 40 years later, suggesting Iversen likely enjoyed many years of comfort and stability. As for dangerous Arctic expeditions, it appears Iversen no longer jumped at every chance to participate.