Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, which marks its 200th anniversary this year, is often regarded as the first modern science fiction novel. It has become so ingrained in popular culture that even those who haven't read it are familiar with (or think they are familiar with) the tale: A young scientist named Victor Frankenstein assembles a grotesque yet somewhat human creature from the remains of dead bodies, only to lose control over his creation, unleashing chaos. This imaginative story emerged from the mind of an extraordinary young woman and simultaneously mirrored the growing concerns over new scientific advancements that were on the brink of reshaping life in the 19th century.

The woman we know as Mary Shelley was born as Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin, daughter to political philosopher William Godwin and the renowned feminist philosopher Mary Wollstonecraft, who tragically passed away shortly after giving birth to Mary. Shelley's upbringing was in an intellectually stimulating environment, where her parents—after Godwin remarried—frequently entertained prominent thinkers. Among them was William Nicholson, a scientist and inventor who extensively wrote about chemistry and the scientific method, and Erasmus Darwin, a polymath and grandfather of Charles Darwin.

At the age of 16, Mary eloped with poet and philosopher Percy Bysshe Shelley, who was married at the time. Percy, a Cambridge graduate, was a passionate amateur scientist with a particular interest in the properties of gases and the chemical composition of food. He was especially fascinated by electricity, even conducting experiments similar to Benjamin Franklin's famous kite experiment.

The origin of Frankenstein dates back to 1816, when Mary and Percy Shelley spent the summer at a lakeside house in Lake Geneva, Switzerland. Lord Byron, the renowned poet, stayed in a nearby villa with his friend, the young doctor John Polidori. The weather was dreadful that summer. (We now know that the eruption of Mount Tambora in Indonesia in 1815 had released dust and smoke into the atmosphere, blocking sunlight for weeks and causing widespread crop failure; 1816 became infamously known as the "year without a summer.")

Mary and her companions, including her baby son William and her step-sister Claire Clairmont, were stuck indoors, gathering around the fire, reading, and telling stories. With storms raging outside, Byron suggested that everyone write their own ghost story. Some of them attempted it; today, it is Mary's tale that endures.

THE SCIENCE THAT INSPIRED SHELLEY

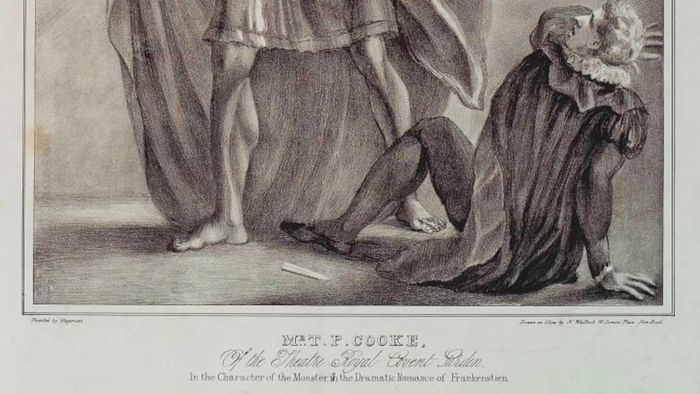

A lithograph from the 1823 production of the play *Presumption; or, the Fate of Frankenstein*, inspired by Shelley's novel. | Wikimedia Commons // Public Domain

A lithograph from the 1823 production of the play *Presumption; or, the Fate of Frankenstein*, inspired by Shelley's novel. | Wikimedia Commons // Public DomainWhile Frankenstein is a fictional tale, it is heavily influenced by real-world science, starting with the adventure framing Victor Frankenstein’s narrative: Captain Walton’s expedition to the Arctic. Walton's goal is to reach the North Pole (an accomplishment not achieved for nearly another century), where he hopes to "discover the wondrous power that attracts the needle," referring to the enigmatic force of magnetism. The magnetic compass, essential for navigation, was known to rely on Earth's magnetic properties, though the mechanisms behind it, and the distinction between magnetic and geographical poles, remained unclear.

It makes sense that Shelley would weave this scientific pursuit into her story. As Nicole Herbots writes in her 2017 book Frankenstein: Annotated for Scientists, Engineers, and Creators of All Kinds, "The connections between electricity and magnetism were a central focus of research during Mary Shelley's time, and many expeditions set out for the poles, hoping to uncover the mysteries of the Earth's magnetic field."

Victor recalls to Walton that during his time at the University of Ingolstadt (still operational today), he became captivated by chemistry. However, his professor, the knowledgeable and approachable Professor Waldman, urged him to explore all areas of science. Unlike today's specialized scientists, those in Shelley's era often had broad scientific interests. Waldman advises Victor: "A man would make but a very sorry chemist if he attended to that department of human knowledge alone. If your wish is to become really a man of science, and not merely a petty experimentalist, I should advise you to apply to every branch of natural philosophy, including mathematics."

The question that most fascinates Victor is the essence of life itself: "the structure of the human frame, and, indeed, any animal endued with life. Whence, I often asked myself, did the principle of life proceed?" He believes science is on the verge of answering this question, though he laments that "cowardice or carelessness" prevents further progress.

In Shelley's time, the debate surrounding what separates living beings from inanimate matter was intense. John Abernethy, a professor at London’s Royal College of Surgeons, championed a materialist view of life, while his student, William Lawrence, supported "vitalism," the notion of a life force, an "invisible substance, analogous to on the one hand to the soul and on the other to electricity."

Another prominent thinker, chemist Sir Humphry Davy, proposed the idea of a life force, envisioning it as a chemical power akin to heat or electricity. Davy's public lectures at London's Royal Institution were immensely popular, and the young Mary Shelley attended these talks with her father. Davy's influence lingered: in October 1816, as she was writing *Frankenstein* nearly every day, Shelley recorded in her diary that she was also reading Davy's *Elements of Chemical Philosophy*.

Davy was also a strong believer in science's ability to better the human condition—a power that was only beginning to be harnessed. Victor Frankenstein echoes this belief: Scientists "have indeed performed miracles," he remarks. "They penetrate into the recesses of Nature, and show how she works in her hiding-places. They ascend into the heavens; they have discovered how the blood circulates, and the nature of the air we breathe. They have acquired new and almost unlimited Powers …"

Victor vows to go even further, to uncover new knowledge: "I will pioneer a new way, explore unknown Powers, and unfold to the world the deepest mysteries of Creation."

FROM EVOLUTION TO ELECTRICITY

Closely tied to the problem of life was the concept of "spontaneous generation," the supposed sudden appearance of life from non-living matter. Erasmus Darwin was a key figure in studying spontaneous generation. He, much like his grandson Charles, wrote about evolution, proposing that all life originated from a single source.

Erasmus Darwin is the only real-life scientist explicitly mentioned in the introduction of Shelley's novel. There, she recounts how Darwin "preserved a piece of vermicelli in a glass case, till by some extraordinary means it began to move with a voluntary motion." She adds: "Perhaps a corpse would be re-animated; galvanism had given token of such things: perhaps the component parts of a creature might be manufactured, brought together, and endowed with vital warmth." (Scholars suggest that "vermicelli" may be a misreading of Vorticellae—microscopic aquatic organisms Darwin studied; he wasn’t trying to bring pasta to life.)

Victor relentlessly pursues his quest to unlock the spark of life. Initially, he "became acquainted with the science of anatomy: but this was not sufficient; I must also observe the natural decay and corruption of the human body." Eventually, he succeeds in "discovering the cause of the generation of life; nay, more, I became myself capable of bestowing animation upon lifeless matter."

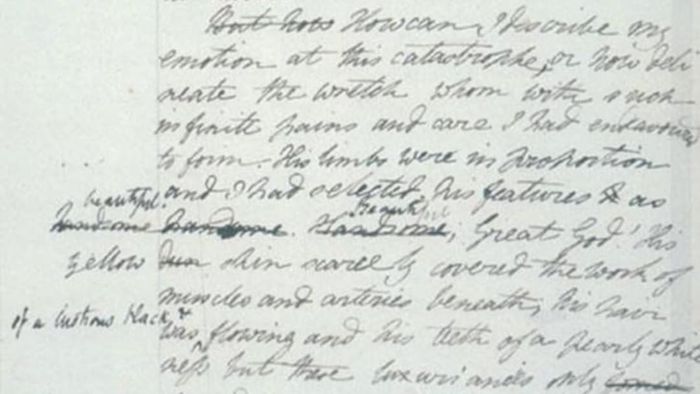

A page from the original draft of *Frankenstein*. | Wikimedia Commons // Public Domain

A page from the original draft of *Frankenstein*. | Wikimedia Commons // Public DomainShelley wisely refrains from explaining the secret—leaving it to the reader's imagination—but it is clear that it involves the emerging science of electricity; it is this, above all, that fascinates Victor.

During Shelley's era, scientists were only beginning to understand how to store and utilize electrical energy. In 1799, Alessandro Volta in Italy created the "electric pile," an early version of the battery. A decade earlier, in the 1780s, his fellow countryman Luigi Galvani claimed to have discovered a new form of electricity through experiments with animals (which led to the term "galvanism"). Galvani famously caused a frog's leg to twitch by passing an electrical current through it, even after the animal's death.

Then there was Giovanni Aldini, Galvani's nephew, who experimented with the body of a hanged criminal in London in 1803. (This occurred long before body donations to science were common, so executed criminals were often used for research purposes.) In Shelley's novel, Victor takes this one step further, sneaking into graveyards to experiment on corpses: "… a churchyard was to me merely the receptacle of bodies deprived of life … Now I was led to examine the cause and progress of this decay, and forced to spend days and nights in vaults and charnel-houses."

Electrical experimentation wasn't limited to the dead; in London, electrical "therapies" became a popular treatment—people with various illnesses sought them out, with some allegedly finding cures. Therefore, the idea that the dead could be revived through electrical manipulation seemed plausible to many, or at least worth scientific investigation.

Another scientific figure worth noting is Johann Wilhelm Ritter, a German physiologist whose work on electricity and batteries, as well as his studies in optics, led him to discover ultraviolet radiation. Davy followed Ritter's work with great interest. However, just as Ritter was starting to gain recognition, he began to unravel. He became isolated from friends and family, and his students abandoned him. Eventually, it seems he experienced a mental breakdown. In *The Age of Wonder*, author Richard Holmes suggests that this now-forgotten German might have inspired the passionate and obsessive character of Victor Frankenstein.

A CAUTIONARY TALE ABOUT HUMAN NATURE, NOT SCIENCE

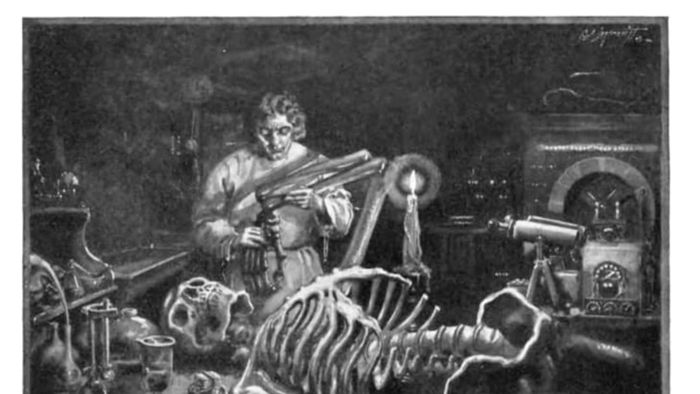

A plate from the 1922 edition of *Frankenstein*. | Wikimedia Commons // Public Domain

A plate from the 1922 edition of *Frankenstein*. | Wikimedia Commons // Public DomainOver time, Victor Frankenstein became the archetypal mad scientist, the first of many characters who would come to define a popular Hollywood stereotype. Victor is so consumed by his experiments that he fails to consider the consequences of his actions; when he realizes the havoc he has caused, he is overwhelmed with guilt and regret.

However, scholars who study Mary Shelley’s work do not interpret this remorse as an indictment of science itself. As the editors of *Frankenstein: Annotated for Scientists, Engineers, and Creators of All Kinds* point out, "*Frankenstein* is unequivocally not an antiscience screed."

It’s important to remember that the creature in Shelley's novel begins as a gentle and thoughtful being, who enjoys reading *Paradise Lost* and reflecting on his place in the universe. His transformation into a vengeful force occurs only after he is repeatedly rejected and mistreated by society. At every turn, people shun him in fear and disgust, forcing him into a life of isolation. It is only after enduring cruelty that his violent actions begin.

"All around me, I see happiness, from which I am forever banished," the creature mourns to his creator, Victor. "I was kind and good—suffering turned me into a monster. Make me happy, and I will become virtuous again."

However, Victor does not take action to relieve the creature’s anguish. Although he initially returns to his lab to create a mate for the creature, he quickly changes his mind, destroying the second creation in fear that "a race of devils would be unleashed upon the world." He swears to hunt down and destroy his creation, vowing to pursue the creature "until either he or I meet our end in a final battle."

Victor Frankenstein’s downfall, it could be argued, was not his obsessive pursuit of science or his desire to "play God." His true flaw lies in his inability to empathize with the creature he brought into existence. The issue is not with Victor’s intellect, but with his compassion.