During the production of his daytime talk show, there might have been a moment when Geraldo Rivera considered securing the chairs to the floor. Such a thought likely crossed his mind in November 1988, while filming an episode named “Young Hatemongers.” The episode featured Black civil rights advocate Roy Innis and white supremacist John Metzger. A heated exchange between the two escalated, leading to Innis attempting to choke Metzger. The stage was soon overrun by supporters from both factions.

Amid the chaos, a chair was hurled through the air, striking Rivera in the face and causing his nose to bleed profusely. Rivera appeared stunned, seemingly bewildered that a debate between a racist and an activist had spiraled into such violence.

Fists of Fury

The 1980s daytime talk show landscape was divided into two distinct styles. On one side, figures like Oprah Winfrey and Phil Donahue hosted programs resembling televised town halls, tackling provocative subjects such as racism and sexism. On the other side, Morton Downey Jr. and Geraldo Rivera paved the way for the likes of Jerry Springer, often featuring guests who turned confrontational or even violent over similar issues.

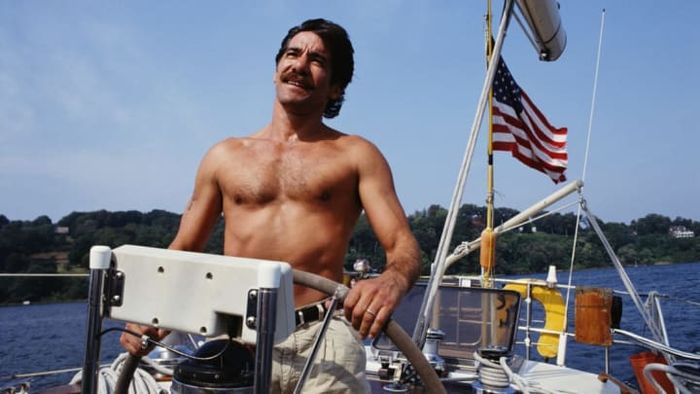

While Winfrey and others had long been established in the talk show arena, Rivera was a newcomer to daytime television. A former ABC News correspondent, Rivera gained prominence in the 1970s through impactful investigative journalism, including his exposé on the Willowbrook State School abuse scandal on Staten Island, which earned him a Peabody Award in 1972.

Transitioning from hard news, Rivera achieved notoriety as the host of The Mystery of Al Capone’s Vaults, a syndicated special that aired on April 21, 1986. The program aimed to uncover the secrets of the infamous mafia leader’s Chicago storage facility but found nothing. Despite the lack of discoveries, the high ratings hinted at Rivera’s potential as a talk show host.

A Star Is Born

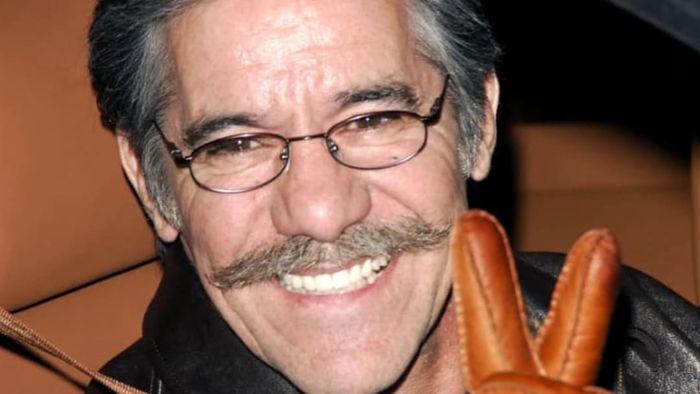

Geraldo Rivera in 2007. | Ray Tamarra/Getty Images

Geraldo Rivera in 2007. | Ray Tamarra/Getty ImagesDebuting in the fall of 1987, Geraldo mirrored its host’s combative approach to journalism. The show thrived on controversial subjects, sparking heated debates that drove ratings. Just two weeks before his infamous nose injury, Rivera hosted the primetime special Devil Worship: Exposing Satan’s Underground, a program steeped in the era’s “satanic panic” frenzy rather than factual evidence. Critics accused Rivera of popularizing sensationalist content, but he defended his platform as a means to expose the disturbing ideologies of racist and immoral guests.

With this philosophy, Rivera and his team organized the November 1988 episode “Young Hatemongers,” which sought to highlight young neo-Nazis. The episode featured Roy Innis, a civil rights leader and head of the Congress of Racial Equality, known for his controversial support of Black nationalism—a movement advocating for separate Black institutions. Jewish leaders like Mordechai Levy of the Jewish Defense Organization and Rabbi A. Goldman of the Center for Jewish Living were also invited. Representing the opposing side were John Metzger, leader of the White Aryan Resistance Youth, and Bob Heick of the American Front. The audience included both neutral attendees and supporters of the featured groups.

A civil discussion was never anticipated. Rivera stationed 10 security guards near the stage. Approximately 38 minutes into the taping, Metzger provoked Innis by saying he was “trying to be a white man.” Innis reacted by lunging at Metzger and grabbing him by the throat.

As Innis and Metzger clashed, around 25 audience members stormed the stage, hurling chairs. Rivera, attempting to regain control, found himself in the chaos. A chair struck him in the head, and he traded blows with an attacker before a second chair hit him. Another man punched him, leaving Rivera with a broken nose.

“Roughly half the audience erupted into a chaotic brawl,” Geraldo spokesperson Jennifer Geertz explained to The Washington Post. “Punches were thrown, fists and bodies were flying everywhere.”

The chaos subsided after security guards removed the white supremacists from the stage. Medical staff offered assistance to Rivera, but he refused immediate care, stating, “There’s not much you can do for a broken nose.” He proceeded to film another episode as planned before undergoing reconstructive surgery.

Ratings Grabber

Despite police involvement, no arrests were made. Innis expressed no remorse for his actions, stating, “I don’t believe I was at fault. I was verbally attacked, and it’s wrong to passively accept such abuse. I acted to defuse the situation, which could have escalated further if I hadn’t intervened.”

Rivera remained unapologetic about the incident, asserting, “Exposing these hateful individuals is crucial. Sunlight is the best disinfectant.” He labeled them as “racist thugs” and “roaches,” praising Innis’s actions as justified. Rivera chose not to press charges, wanting no further association with the hate groups. (In 1990, Metzger faced legal consequences for the death of Mulugeta Seraw, an African immigrant killed by skinheads in Portland, Oregon. Metzger and his father were held financially responsible in a civil court, resulting in a $12.5 million judgment.)

News outlets quickly seized on the details of the altercation, demanding access to the unedited footage. The episode aired a few weeks later, boosting ratings and drawing significant attention to Rivera and his show. This reignited the debate over whether Rivera was genuinely exposing racists or simply capitalizing on racial tensions for viewership.

This incident was not the last time Rivera found himself embroiled in violence due to his talk show, which continued until 1997. In 1992, while covering a Ku Klux Klan gathering in Janesville, Wisconsin, Rivera was attacked by a man named John McLaughlin. Rivera fought back, reportedly knocking out some of McLaughlin’s teeth. Both men, along with eight others, were arrested. Later, in 1995, an episode focusing on domestic violence also turned physical, resulting in Rivera breaking his nose once more.