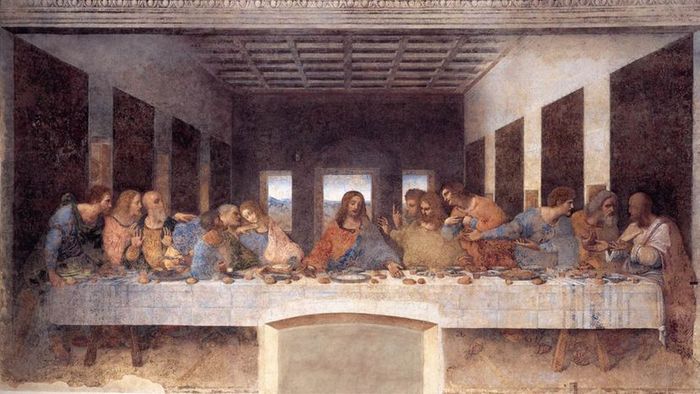

Da Vinci employed a unique technique to create 'The Last Supper,' using oil and tempera on a dry wall. Unfortunately, this method proved less durable, leading to paint flaking and a fresco that has struggled to endure over the centuries. Wikimedia Commons

Da Vinci employed a unique technique to create 'The Last Supper,' using oil and tempera on a dry wall. Unfortunately, this method proved less durable, leading to paint flaking and a fresco that has struggled to endure over the centuries. Wikimedia CommonsAdorning the wall of Milan's Convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie is a piece often hailed as one of history's greatest artistic achievements. However, its creator, Leonardo da Vinci, was far from enthusiastic when Ludovico Sforza, the Duke of Milan, commissioned the work in 1494.

"Leonardo had no desire to paint 'The Last Supper,'" explains Ross King, author of "Leonardo and The Last Supper." "His ambition was to craft a massive bronze equestrian statue—a project that would have cemented his legacy. However, the war in 1494 disrupted his plans, forcing him to settle for painting a wall in a friars' dining hall. This was uncharted territory for him, as he had never tackled such a large-scale painting. Given his lack of experience, it's no wonder he expressed frustration and feared failure. Fortunately, the outcome defied his expectations."

Da Vinci's reluctant involvement led to the creation of a mural that vividly portrays Jesus Christ's final meal with his apostles, the evening before his crucifixion. Inspired by the Gospel of John 13:21, the artwork captures the disciples' varied reactions as they realize one among them would betray Jesus.

King, author of notable works such as "Brunelleschi's Dome" and "Michelangelo and the Pope's Ceiling," emphasizes the significance of da Vinci's "The Last Supper." He highlights how the mural elevated da Vinci to celebrity status, marking a turning point in his career. "This masterpiece, completed in his mid-40s, was what Leonardo called a 'work of fame,'" King explains. "Before this, Leonardo had accomplished little. Had he passed away in 1492 at age 40, he would have been a mere footnote in art history. But 'The Last Supper' changed everything, paving the way for future commissions like the 'Mona Lisa.' It was pivotal not just for art history but for Leonardo's legacy."

A standout aspect of "The Last Supper" is its monumental scale. "No artist before Leonardo had attempted such a large painting with such intricate realism and emotional depth," King notes. The mural, measuring roughly 15 feet by 29 feet (4.5 meters by 8.8 meters), set a new standard. "Every subsequent depiction of the Last Supper was inevitably influenced by Leonardo's groundbreaking work."

Da Vinci chose to depict a critical moment in his rendition: the seconds leading up to the institution of the Eucharist. Jesus reaches for the bread, symbolizing his body, and the wine, representing his blood. This scene aligns with the account in Corinthians 11:23-26, which describes the event as follows:

Who Are the Subjects?

Da Vinci's notebooks provide insights into the identities of the figures in the painting, though some details remain debated. In one cluster, Bartholomew, James (son of Alpheus), and Andrew appear visibly stunned by Jesus' revelation. Another group includes Judas Iscariot, Peter, and John. Judas, the betrayer, is subtly depicted: he recedes into the background, clutches a money bag, and knocks over a salt shaker, symbolizing betrayal. Jesus occupies the center, flanked by Thomas, James the Greater, and Philip. Completing the scene are Matthew, Jude Thaddeus, and Simon the Zealot. The balanced arrangement of the figures reflects da Vinci's signature style, emphasizing symmetry and perspective to create visual harmony.

However, the enduring fame of "The Last Supper" isn't solely due to its content and composition. "The painting has faced a tragic history," King notes. "The paint began peeling because of unfavorable conditions in the refectory—cold and damp. This might have been less problematic had Leonardo used traditional fresco techniques, known for their durability. Instead, he experimented with oil and tempera on a dry wall, a method discouraged by experts. Unsurprisingly, his approach proved unsuccessful."

Da Vinci's questionable methods and centuries of poor preservation left "The Last Supper" in a deteriorated state. Matters worsened over time. "The painting suffered from inept restoration attempts that caused more damage than repair," King explains. "In 1652, the friars vandalized the mural by cutting a doorway through it, severing Christ's feet. The refectory flooded in the 1800s, and Napoleon repurposed the space as a stable, exposing it to horses and filth. During World War II, a bomb devastated much of the refectory, yet the painting miraculously survived. Its existence today is nothing short of a miracle."

Art scholars continue to analyze and debate numerous details in "The Last Supper." For instance, the fish on the table raises questions: Is it herring or eel? In Italian, "eel" is "aringa," while "arringa" means "indoctrination." The northern Italian term for "herring," "renga," refers to someone who denies religion.