The 1983 cultural phenomenon Flashdance has a complex and intricate history. Among the many tales surrounding it, one particularly intriguing urban legend has fascinated horror enthusiasts: Michael Sembello’s synth-heavy track “Maniac,” which topped the Billboard Hot 100, was allegedly first composed for the 1980 exploitation film Maniac, a gruesome story about a serial killer who scalps his female victims.

Legend suggests the song originally featured lyrics like, “He’s a maniac, maniac, that’s for sure / He’ll kill your cat and nail him to the floor.” (Some versions say “door”; details differ.) A 1998 episode of VH1’s Pop Up Video claimed the early rendition of the song depicted “a maniac who severed people’s arms and feet.” However, only fragments of this tale hold truth—and surprisingly, not the most plausible parts.

Nail It to the Floor

By the time filming began for Flashdance in October 1982, Michael Sembello, then in his late twenties, had already established himself as a skilled session musician and songwriter. At just 17, he secured a position playing guitar for Stevie Wonder, a role he maintained for eight years. (Sembello’s musical roots ran deep; his older brother, John, collaborated on songs for the Lovin’ Spoonful and Chaka Khan, while his younger brother, Daniel, co-wrote the Pointer Sisters’ “Neutron Dance,” another ’80s soundtrack staple featured in Beverly Hills Cop.)

Collaborating with Wonder, including co-writing a track on the Grammy-winning 1976 album Songs in the Key of Life, paved the way for Sembello to work with icons like Donna Summer, Diana Ross, Art Garfunkel, and Michael Jackson. However, the Philadelphia-born artist grew restless contributing to others’ projects. “You sacrifice a piece of yourself to fulfill someone else’s vision,” he shared with The Philadelphia Inquirer in 1983.

Eager to forge his own path, Sembello built a home studio in Los Angeles. By 1982, he was crafting his debut solo album, which would later become 1983’s Bossa Nova Hotel. His longtime friend and fellow Philadelphian Dennis Matkosky, with whom he had co-written Diana Ross’s Top 10 hit “Mirror, Mirror,” joined him in the songwriting process.

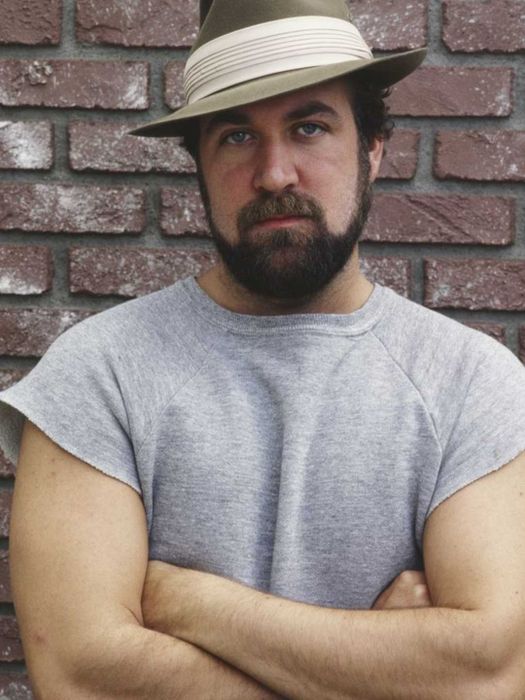

As Sembello sought to break out as a solo artist, his collaborator Dennis Matkosky drew inspiration from an unexpected place. | George Rose/GettyImages

As Sembello sought to break out as a solo artist, his collaborator Dennis Matkosky drew inspiration from an unexpected place. | George Rose/GettyImagesIn a 2022 episode of the YouTube series Starting Small Music, Matkosky recounted how a chilling news report one evening sparked his creativity.

“They discovered numerous bodies in ... Gacy’s backyard,” Matkosky explained. “I jotted down on a piece of paper, ‘He’s a maniac, he just moved next door. He’ll kill your cat and nail it to the floor. He’ll rape your mother and screw your wife. He’s a maniac.’” (John Wayne Gacy, arrested in 1978 and convicted in 1980, might not have been the exact inspiration, as Matkosky’s memory could be hazy. However, Gacy’s lengthy appeals, the public’s obsession with his crimes, and his penchant for self-serving interviews kept him in the headlines during 1982 and 1983, coinciding with the production of Flashdance and its legendary soundtrack.)

Matkosky shared the lyrics and title with his wife, who gently recommended he seek professional help. The next day, he brought the hastily written lyrics to Sembello, a lifelong horror enthusiast who had grown weary of composing love songs.

And then things took a strange turn.

The Devil’s Interval

Years before Sembello and Matkosky created their iconic hit, another Maniac had already gripped the public’s imagination. Known for its graphic violence, eerie synth score, and a gritty, oppressive atmosphere, the film Maniac stirred significant controversy upon its 1981 theatrical release.

To sidestep an X rating, the American distributor, alongside director William Lustig and Joe Spinell—the film’s co-writer, co-producer, and lead actor—chose to release the movie with a “For Adults Only” label instead of an MPAA rating. This decision limited its screening in mainstream theaters. Feminist groups reportedly protested venues that showed the film, and the LA Times refused to advertise it due to its portrayal of brutal violence.

Even the promotional poster faced censorship; the original artwork, depicting a man holding a bloody scalp and a knife while standing in a pool of blood with a visible erection, was deemed too graphic for public display. However, grindhouse theaters embraced it, helping the film earn an estimated $10 million against its $350,000 budget.

One element Spinell felt the film lacked was a memorable theme song. A seasoned character actor with roles in The Godfather and Taxi Driver, Spinell was also a horror aficionado eager to leave his mark on the genre. Inspired by the chart-topping success of Michael Jackson’s “Ben” from the 1972 killer-rat film, Spinell insisted Maniac needed a standout pop track. Despite Jay Chattaway’s score, the film produced no breakout hits, nothing close to the acclaim the Flashdance soundtrack would achieve shortly after.

By the time Maniac reached home video, Sembello and Matkosky were crafting their own gruesome anthem. “I thought, ‘Why not write a song about a serial killer who decapitates people, like in Halloween III?’” Sembello told The Philadelphia Inquirer in 1983. (Note: This does not occur in Halloween III.) The duo developed the song while relaxing in Sembello’s hot tub, with Matkosky playing “the strangest chord [he] knew.” The track came together in just 15 minutes.

Their main inspiration came from a haunting 1971 track titled “D.O.A.” by the Texas rock band Bloodrock, which tells the story of a man fatally injured in a plane crash. The song’s use of an ambulance siren inspired the jarring musical interval in “Maniac”: a tritone, typically consisting of two notes separated by three whole steps. This interval is so notoriously dissonant that it was historically referred to as diabolus in musica, or “the devil in music.”

Matkosky revealed that he and Sembello had no serious intentions for their song—no plans whatsoever. Although Matkosky rented the 1980 film Maniac during the songwriting process, primarily because it shared the same title as their composition, it had little to no influence on their work. The song was never intended for the film, and they didn’t even complete it, recording only a partial version as a humorous demo for friends.

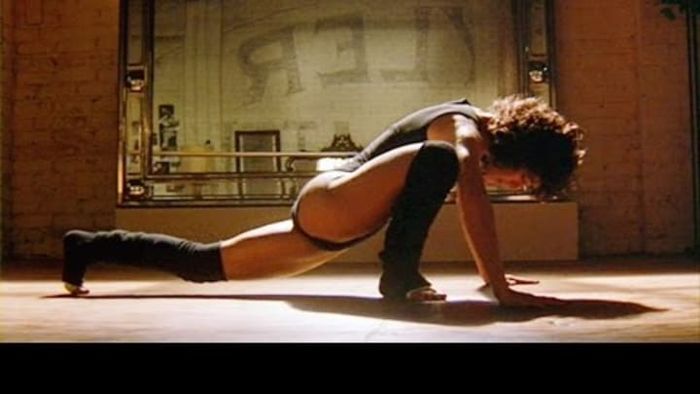

However, much like the themes in other controversial ’80s films by Adrian Lyne, “Maniac” was destined to be noticed. Sembello mistakenly sent the track to producer Phil Ramone, who was curating music for the Flashdance soundtrack. In a 1983 interview with The Los Angeles Times, Sembello shared that Ramone wanted the song for the movie but requested they “tone down the horror elements” and align it more with the story of Alex Owens, a Pittsburgh welder and exotic dancer aspiring to become a ballerina.

Stretching for the Beat

Flashdance debuted in April 1983 with little initial buzz. Critics were lukewarm, and Paramount had such low expectations that they essentially dismissed it as a financial flop before its release. However, audiences embraced the film; by the end of December, Flashdance had grossed nearly $93 million domestically, trailing only Return of the Jedi and Tootsie in box office earnings that year.

The soundtrack LP, released by PolyGram, was met with equal enthusiasm, prompting the label to rush to meet demand and saturate record stores with promotional materials and displays. Paramount swiftly brought Flashdance director Adrian Lyne into the editing room to assemble outtakes into music videos for four tracks, including “Maniac.” The video became a staple on MTV and in dance clubs nationwide, propelling the single’s success and offering significant free publicity for the film. In an essay for the 2011 book Celluloid Symphonies, music critic Marianne Meyer highlights how these videos revolutionized film marketing strategies.

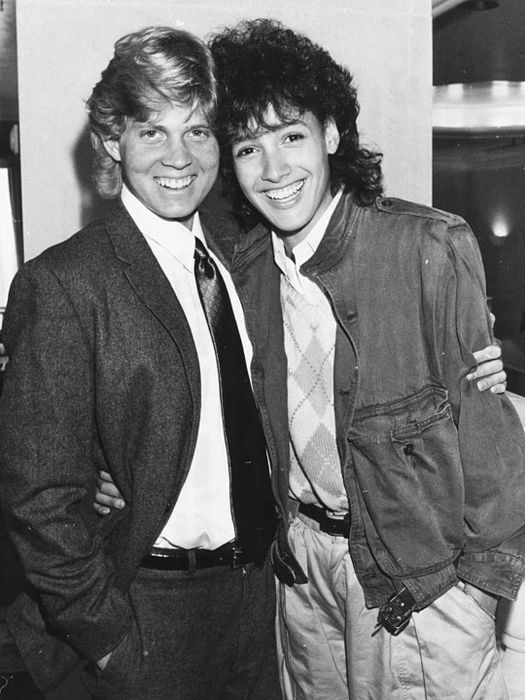

Actress Jennifer Beals and film producer Rob Simonds at the premiere of 'Flashdance' in London. | Dave Hogan/GettyImages

Actress Jennifer Beals and film producer Rob Simonds at the premiere of 'Flashdance' in London. | Dave Hogan/GettyImagesBy September, “Maniac”—the second single from the film, following Irene Cara’s empowering “Flashdance... What a Feeling” [PDF]—had climbed to No. 1 on the Billboard Hot 100. In 1984, the track earned an Oscar nomination for Best Original Song, though Sembello lost to Cara at the 56th Academy Awards. Sembello later contributed songs to other soundtracks, such as “Mega Madness” for 1984’s Gremlins and “Rock Until You Drop” for 1986’s The Monster Squad, but none matched the success of “Maniac.”

Over time, a myth about the song’s origins began to circulate. When “Maniac” debuted in 1983, Spinell called Lustig, insisting it was written for their film. Lustig dismissed the claim, attributing it to Spinell’s recreational drug use—until years later, when Lustig watched an episode of VH1’s One-Hit Wonders where Sembello appeared to validate Spinell’s assertion.

In May 2010, Lustig visited Sembello’s home to definitively uncover the origins, purpose, and creation process of the song. Their discussion, later featured on a special-edition Blu-ray of Maniac, finally clarified the truth. The song initially began as a peculiar tune about a psychotic murderer—but it had almost no connection to Lustig’s film.

As for Spinell, the actor was adamant about producing and starring in a sequel to his infamous slasher film, despite his character, Frank Zito, seemingly committing suicide at the end. Lustig had no interest, but according to Dave Alexander’s 2023 book Untold Horror, Spinell spent years developing two unsuccessful follow-ups. Allegedly influenced by the backlash from women’s groups over Maniac, he first envisioned a sequel centered on a children’s show host who targeted child abusers. An eight-minute promo reel titled Maniac 2: Mr. Robbie was created in 1986, but the project collapsed after Spinell and his director lost the only script copy.

Spinell then shifted focus to Lone Star Maniac, which would have cast him as a homicidal Texas DJ. On January 13, 1989, just three weeks before filming was to start, Spinell passed away in his Queens apartment. While his death was widely reported as a heart attack, some sources suggest he had hemophilia and died from bleeding after a head injury from a fall. Efforts to create an official Maniac sequel ended with him. However, the film was remade in 2012 by French director Franck Khalfoun, starring Elijah Wood in the lead role—yet still lacking a memorable pop song to complement its more refined synth score.