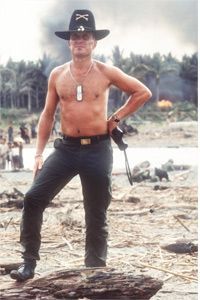

Robert Duvall, portraying Lt. Col. Kilgore in "Apocalypse Now," famously remarked about his fondness for the scent of napalm in the morning.

Matthew Naythons/Getty Images

Robert Duvall, portraying Lt. Col. Kilgore in "Apocalypse Now," famously remarked about his fondness for the scent of napalm in the morning.

Matthew Naythons/Getty ImagesDepending on the perspective, napalm can be seen as a noun, a verb, a chemical weapon, a means to eradicate weeds, a representation of the horrors of war, or simply a memorable movie quote. Napalm, with its diverse forms and extensive military history, is both iconic and often misinterpreted. This article explores the origins of napalm, its modern applications, and the reason behind its notorious odor.

According to GlobalSecurity.org, napalm is defined as "a tactical weapon designed to eliminate vegetation and induce terror." It originates from a powdered substance combined with gasoline in certain formulations. Known as a firebomb fuel gel mixture, napalm has a gel-like texture that enables it to adhere to surfaces. Typically, it is blended with gasoline or jet fuel to create a bomb with a fragile casing that detonates and ignites upon hitting a target. Once ignited, napalm can reach temperatures exceeding 5,000 degrees Fahrenheit (2,760 degrees Celsius).

Napalm is highly valued by military strategists for its effectiveness against fortified locations such as bunkers, caves, and tunnels, as well as vehicles, convoys, small bases, and structures. Its adhesive quality ensures it sticks to surfaces, generating a widespread, intensely burning zone around the target. This characteristic also reduces the precision required when deploying napalm bombs.

During World War I, U.S. and German forces experimented with an early version of napalm in flamethrowers. However, these weapons proved inefficient as the gasoline used would simply drip off targets. Military strategists realized the need for a thicker, more adhesive fuel solution.

A breakthrough came from Dr. Louis F. Fieser and his team of scientists. They developed a mixture using aluminum soap, naphthenic acid derived from crude oil, and palmitic acid from coconut oil. (The name "napalm" is derived from "na" in naphthenic and "palm" in palmitic.) When blended with gasoline, this new compound created an inexpensive yet devastatingly effective weapon. It could be launched over long distances and posed fewer risks to the soldiers handling it.

Napalm, in its various forms, has been utilized by numerous militaries, though its deployment, particularly in civilian areas, remains highly contentious. The 1980 United Nations Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons banned the use of napalm against civilians. Protocol III of the convention specifically prohibited the use of incendiary weapons like napalm on civilian populations. While the United States ratified the convention, it did not agree to Protocol III and has continued to employ napalm in multiple conflicts since its creation.

Napalm's Effects on Health and the Environment

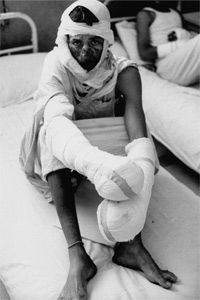

An Egyptian soldier, severely burned by napalm during the Arab-Israeli war, receives medical attention at Helmia Military Hospital.

Charles Bonnay//Time Life Pictures/Getty Images

An Egyptian soldier, severely burned by napalm during the Arab-Israeli war, receives medical attention at Helmia Military Hospital.

Charles Bonnay//Time Life Pictures/Getty ImagesNapalm is an exceptionally devastating weapon. Its adhesive nature allows it to cling to skin even after ignition, leading to severe burns. Due to its extreme heat, even brief exposure can cause second-degree burns, often resulting in permanent scars known as keloids. Medical professionals, such as those from Physicians for Social Responsibility, find burns from incendiary weapons like napalm particularly challenging to treat [source: Crawley].

Napalm can be fatal, causing death through severe burns or suffocation. When napalm bombs detonate, they produce carbon monoxide while depleting oxygen levels in the surrounding area. In some cases, the air in bombed zones can contain over 20 percent carbon monoxide [source: GlobalSecurity.org]. This occurs because napalm partially burns the oxygen, converting CO2 (carbon dioxide) into CO (carbon monoxide). In extreme instances, individuals have died from being boiled alive in water heated by napalm explosions.

The components of napalm can also pose health risks, though they are far less dangerous than when ignited. For example, inhaling fumes at a gas station can cause dizziness, offering a mild comparison. However, when polystyrene, a common napalm ingredient, burns at high temperatures, it transforms into toxic styrene [source: GlobalSecurity.org].

While napalm was initially used in agriculture—Dr. Fieser discovered it could eliminate crabgrass by burning its seeds without harming other plants—it has primarily been an environmental hazard. Fires ignited by napalm can cause extensive ecological damage. During the Vietnam War, the U.S. military used napalm to obliterate forests that provided cover for North Vietnamese troops. The widespread deployment of napalm, alongside Agent Orange, herbicides, and unexploded landmines, is believed to have contributed to Vietnam's persistent environmental and health challenges [source: King].

In the United States, the disposal of unused napalm has sparked significant controversy. In 1998, protests halted trains transporting napalm to recycling facilities, driven by fears of leaks similar to those at the Weapons Support Facility, Fallbrook Detachment, in Southern California. This final stockpile of napalm in the U.S. arsenal was eventually dismantled and recycled in 2001.

Authorities in the U.K. once contemplated using napalm to incinerate the carcasses of thousands of animals culled due to foot-and-mouth disease. The plan was rejected over fears of releasing "highly toxic compounds" during the burning process [source: U.K. Parliament].

Napalm in World War II and Korea

The city of Dresden, Germany, was devastated by Allied napalm bombings during World War II.

William Vandivert//Time Life Pictures/Getty Images

The city of Dresden, Germany, was devastated by Allied napalm bombings during World War II.

William Vandivert//Time Life Pictures/Getty ImagesDuring World War II, U.S. forces employed a 6 percent napalm mixture in flamethrowers. Later in the war, napalm bombs became a key component of aerial assaults. In 1944, the Allies launched their first napalm bomb attack on Tinian Island, part of the Northern Mariana Islands in the Pacific. Napalm proved catastrophic for Japanese cities, particularly due to their wooden structures. A napalm raid on Tokyo on March 9, 1945, resulted in approximately 100,000 deaths and burned 15 square miles (39 square kilometers) of the city [source: Laney].

During World War II, Allied forces deployed napalm extensively in Europe, with approximately 3.4 kilotons of napalm bombs—up to 50 percent of all bombs dropped—targeting Dresden in February 1945 [source: GlobalSecurity.org]. This bombing, famously depicted in Kurt Vonnegut's "Slaughterhouse-Five," was part of a highly controversial operation that resulted in the deaths of between 35,000 and 135,000 German civilians [source: Encyclopaedia Britannica].

U.S. forces utilized napalm effectively against German bunkers. Even if the explosion didn't eliminate the soldiers inside, the intense heat often proved fatal. Similar strategies were employed against Japanese troops on Pacific islands, who relied on extensive underground tunnel networks for defense.

While World War II served as napalm's initial testing ground—albeit one marked by immense destruction and casualties—the Korean War marked its widespread adoption. U.S. forces employed napalm on a massive scale during the Korean conflict, ironically relying on supplies manufactured in Japan. Daily, they dropped 250,000 pounds (113,398 kilograms) of napalm bombs, primarily using the M-47 napalm bomb and the M-74 incendiary bomb [source: GlobalSecurity.org]. These were deployed by high-altitude and dive-bombers to target enemy tanks and troops.

Following the Korean War, the United States developed an enhanced version of napalm. This new formulation no longer relied on naphthenic and palmitic acids, which had inspired the original name. By this time, "napalm" had become a generic term for various incendiary weapons, much like "Coke" is used for soda or "Kleenex" for tissues. Napalm-B, also known as super-napalm, NP2, or Incendergel, consists of 33 percent gasoline, 21 percent benzene, and 46 percent polystyrene [sources: Browne, GlobalSecurity.org]. The gasoline used in napalm is similar to standard fuel, but with increased benzene levels for greater effectiveness.

Napalm-B was regarded as safer than its predecessors, though "safety" in this context primarily benefited those deploying the weapon rather than its targets. One of its key safety features was its reduced susceptibility to accidental ignition. To ignite Napalm-B, thermite, a chemical compound that burns at extremely high temperatures, is often used in conjunction with a fuse.

Next, we explore the role of napalm in Vietnam, where it gained its notorious and contentious reputation.

During World War II, the German term "bombenbrandschrumpfeichen" emerged in reaction to napalm attacks on German bunkers. The intense heat would essentially bake soldiers inside, and the term translates to "firebomb shrunken flesh" [source: GlobalSecurity.org].

Napalm in Vietnam

Kim Phuc, pictured here with then-Senator Joe Biden, stands before the iconic photograph of herself as a child, suffering from napalm burns.

Scott J. Ferrell/Congressional Quarterly/Getty Images

Kim Phuc, pictured here with then-Senator Joe Biden, stands before the iconic photograph of herself as a child, suffering from napalm burns.

Scott J. Ferrell/Congressional Quarterly/Getty ImagesDuring the Vietnam War, the U.S. military deployed Napalm-B on a massive scale—up to 400,000 tons (362,874 metric tons) [source: GlobalSecurity.org]. Iconic scenes from movies or newsreels of the era often show planes diving low and then sharply ascending as massive fireballs erupt below. These were likely napalm strikes. A retired U.S. Air Force Lieutenant Colonel described the effect to the San Francisco Chronicle as "a fiery blanket that consumes everything in its path" [source: Taylor].

The Vietnam War produced countless images of destruction, but none is as iconic as the photograph of Phan Thi Kim Phuc, captured by Associated Press photographer Nick Ut. At just 9 years old, Kim Phuc and her village were accidentally struck by napalm from a South Vietnamese plane. The haunting image shows Kim Phuc and other children fleeing their village, with Phuc naked and screaming as napalm scorches her body.

Recognizing the severity of her injuries, Ut rushed Kim Phuc to a hospital. She survived but suffered extensive third-degree burns and underwent 17 surgeries. In her late teens and early 20s, the Vietnamese government exploited her as a propaganda symbol, forcing her to speak to foreign journalists. Eventually, she and her husband escaped to Canada. Now residing near Toronto, she continues to endure pain from her injuries but uses her voice to highlight the atrocities of napalm [source: Omara-Otunnu]. She also serves as a U.N. Goodwill Ambassador. Ut’s photograph, alongside images of self-immolating monks, remains one of the most recognizable visuals from the war.

Napalm's use in Vietnam fueled the antiwar movement in the United States. Dow Chemical Company, which produced napalm for the U.S. government from 1965 to 1969, became a primary target. Protests and boycotts against Dow erupted nationwide, with company recruiters facing intense backlash on college campuses, sometimes being trapped in buildings. Dow defended itself by stating it had a duty to fulfill government requests and that napalm accounted for only 0.5 percent of its total sales [source: BusinessWeek]. After Dow's contract ended, American Electric Inc. took over napalm production. While other companies also faced protests, none became as synonymous with napalm as Dow.

Although the U.S. government officially disposed of its last napalm stockpile in 2001, some argue that napalm is still being used in Iraq today.

The MK-77 and Napalm in Iraq

Pictures like this, showing napalm explosions south of Saigon, became iconic during the Vietnam War. However, napalm's use has not ceased since then.

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Pictures like this, showing napalm explosions south of Saigon, became iconic during the Vietnam War. However, napalm's use has not ceased since then.

Hulton Archive/Getty ImagesSince its creation, napalm has been employed by numerous militaries worldwide, including those of the United States, Angola, Nigeria, Brazil, Egypt, Israel, Argentina, Serbia, Turkey, and possibly others. Today, the U.S. military's only incendiary bomb is the MK-77, or Mark 77 bomb. The MK-77 features a lightweight aluminum casing [source: Iraq Analysis Group]. This unguided, or "dumb," bomb—as opposed to precision-guided "smart" bombs—contains a mixture of 63 gallons (238 liters) of jet fuel (primarily kerosene) and 44 pounds (20 kilograms) of a polystyrene-based gel [source: Buncombe]. Though technically an incendiary bomb, the MK-77 is often informally called napalm by soldiers, experts, and even in some military records, reflecting the term's broader usage.

In the Persian Gulf War, U.S. forces deployed approximately 500 MK-77 bombs [source: GlobalSecurity.org]. These bombs targeted trenches dug by Iraqi forces and filled with oil. Iraqi troops planned to ignite these trenches as U.S. forces advanced, but U.S. soldiers preemptively lit them using napalm to clear the area. After the conflict, Iraqi Kurds rebelled against Saddam Hussein's regime, and in retaliation, Hussein's forces used napalm to brutally suppress the uprising.

While the U.S. military denies using napalm in Afghanistan or Iraq, some experts argue this is merely a matter of terminology [source: GlobalSecurity.org]. They claim that although the traditional form of napalm is no longer used, a similar jelled incendiary substance, such as the MK-77 bomb, has been deployed in these conflicts.

In 2003, U.S. pilots acknowledged deploying napalm against Iraqi troops. A U.S. commander told The Independent that napalm was favored for its "psychological impact" [source: Buncombe]. A Marine Corps Major General also confirmed its use in Iraq [source: Crawley]. A Marine spokesperson noted that the MK-77 Mod 5 bombs used in Iraq were "very similar" to napalm, though less harmful to the environment, and referred to them as "firebombs" [source: Crawley].

There have been claims that napalm was utilized during the U.S. assault on Fallujah in November 2004 [source: Iraq Analysis Group]. However, this remains disputed, with some suggesting that white phosphorous, another controversial incendiary weapon, may have been used instead [source: FAIR].

The deployment of napalm or similar weapons has sparked controversy, particularly among U.S.-allied nations that signed U.N. Protocol III but collaborated with or were under the command of U.S. forces using napalm. The revelation that MK-77 firebombs were dropped during the Iraq War upset British officials, who accused the U.S. of providing misleading information about their use in 2005 [source: BBC News].

Regardless of the final judgment, napalm, like Agent Orange, has become a powerful symbol of war's devastation and cruelty. During the Vietnam War, slogans like "Dow Shall Not Kill" and the iconic photo of Kim Phuc became emblematic of the antiwar movement. While experts argue that napalm, like other weapons, is part of warfare's inherent horrors, its unique imagery and the stories surrounding it have cemented its place as a lasting symbol of conflict's brutality.