In the seventh chapter of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Alice joins the Mad Hatter’s tea party, seated between the March Hare and a drowsy dormouse:

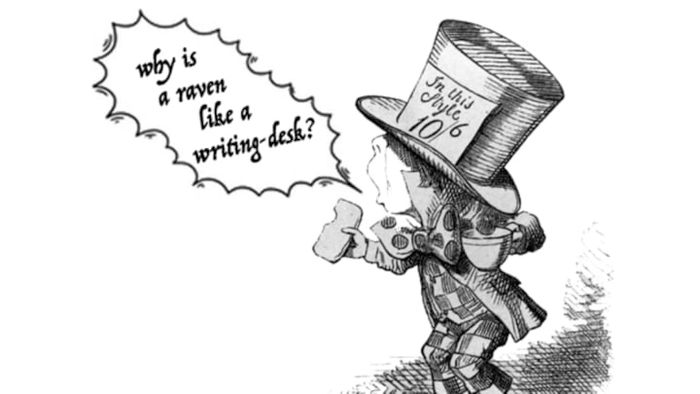

The table was vast, yet the trio huddled tightly at one corner. “No space! No space!” they exclaimed as Alice approached. “There’s more than enough room!” Alice retorted, settling into a spacious armchair at the table’s edge. “Your hair needs a trim,” remarked the Hatter, who had been observing Alice intently. This was his first comment. “You ought to avoid making personal observations,” Alice replied sternly. “It’s quite impolite.” The Hatter’s eyes widened at her response, but all he uttered was, “Why is a raven like a writing-desk?”

The tea party, filled with rapid-fire humor and absurdity—and bolstered by the enduring fame of the book and its many adaptations—stands as one of the most iconic moments in children’s literature. Similarly, the Mad Hatter’s riddle persists as one of Lewis Carroll’s most famous and famously unsolvable enigmas.

Lewis Carroll, a mathematics lecturer at Oxford University’s Christ Church College (the pseudonym of Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, an author, scholar, and Anglican clergyman), crafted numerous riddles and logic puzzles during his life, including several acrostic poems and a later collection of seven poetic conundrums titled “Puzzles from Wonderland,” released in 1870. Yet, the Mad Hatter’s riddle remains a beloved favorite—so why is a raven like a writing-desk?

In the original tale, after much thought, Alice surrenders and asks the Hatter for the solution. “I haven’t the faintest clue,” he responds. However, the Mad Hatter’s failure to solve his own riddle has inspired fans of the book (as well as enthusiasts of word games and logic puzzles) to suggest numerous possible answers since Alice in Wonderland was first published in 1865.

One theory proposes that both ravens and writing-desks possess “bills” and “tails” (or “tales,” in the context of a writer’s desk). Another idea highlights that both can “flap” (a nod to the hinged tops of certain antique desks). Additionally, both were famously utilized by Edgar Allan Poe, whose poem "The Raven" debuted two decades prior. While these explanations (and many others like them) are plausible, none satisfied Carroll himself—who eventually revealed in the preface to an 1896 Christmas edition of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland:

So many inquiries have been made about whether an answer to the Hatter’s riddle exists that I might as well document what seems a reasonably fitting solution here, namely: ‘Because it can produce few notes, though they are very flat; and it is never placed with the wrong end forward!’ However, this is merely an afterthought; the riddle, as originally conceived, had no answer whatsoever.

While some scholars argue that Carroll initially spelled never as "nevar" (raven spelled backward) before an editor corrected it, it seems Carroll’s riddle was never meant to have an answer—though that doesn’t mean it’s entirely without meaning.

Although Carroll held a lectureship at Oxford for over 25 years, he maintained strong connections to northern England. At 11, his father Charles became rector of the Anglican church in Croft-on-Tees, North Yorkshire, where the family resided for the next quarter-century. Two of Carroll’s sisters, Mary and Elizabeth, lived in Sunderland on England’s northeast coast, alongside several cousins, nieces, and nephews. Mary’s husband, Charles Collingwood, served as reverend at a local Anglican church. Additionally, one of Carroll’s closest Oxford friends, Henry George Liddell, Dean of Christ Church College, hailed from a prominent family and was related to the Baron of Ravensworth, whose influence spanned the northeast.

Consequently, Carroll reportedly cherished spending time in northern England during university breaks, visiting friends and family in the area. It was during these visits that he famously crafted stories to amuse Henry Liddell’s young daughter, Alice.

It’s widely acknowledged that Alice Liddell inspired the titular character of Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland. Carroll allegedly conceived the story during a boating excursion in Oxford shortly after Alice and her sisters moved there with their father in 1856. However, it’s plausible that parts of Alice in Wonderland—particularly the Mad Hatter’s riddle—were either penned in northern England or influenced by Carroll’s ties to the region. While visiting the Liddell estate, Carroll stayed at an inn (now called the Ravensworth Arms) in Lamesley, near Ravensworth Castle in Gateshead. During this period, Carroll is thought to have drafted the initial version of Alice in Wonderland. If true, the “raven” in the Mad Hatter’s riddle might reference the Liddells’ Ravensworth Estate, which effectively served as Carroll’s “writing-desk” while he composed the book.

Carroll is known to have woven elements from his northern England experiences into his works: For example, the beach at Whitburn, near Sunderland where his sisters lived, is widely believed to have inspired The Walrus and the Carpenter. Similarly, the fearsome Jabberwock is thought to derive from local legends like the Lambton Worm, a dragon-like creature said to have roamed the Durham countryside. Could the Ravensworth connection be another instance of Carroll drawing from his northern roots, explaining why a raven is like a writing-desk? While it doesn’t solve the riddle, it offers a compelling theory.