Over the last 5000 years, human civilization has evolved dramatically—yet our penchant for deception, fraud, and trickery has remained remarkably consistent. In their latest work Hoax: A History of Deception (Black Dog & Leventhal), Ian Tattersall and Peter Névraumont delve into five millennia of human cons, exploring schemes ranging from bogus real estate deals to fantastical claims of time travel. This excerpt uncovers a complex art theft that resulted in the discovery of six replicas of Leonardo da Vinci's iconic masterpiece.

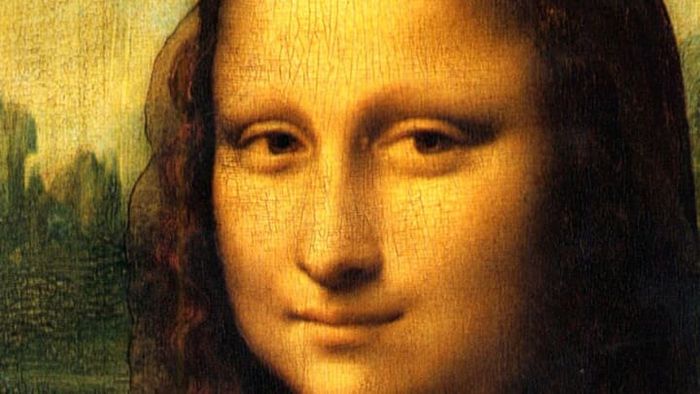

Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa stands as the most renowned painting of the Renaissance era. Housed in Paris’s Louvre museum, it’s now a challenge for visitors to appreciate up close. Sturdy barriers and a thick velvet rope keep admirers at a distance, while swarms of tourists wielding smartphones often block the view entirely. While Leonardo’s Virgin and Child with Saint Anne can be admired in relative peace, the Mona Lisa is often obscured by the bustling crowd. Adding to the challenge, the painting is safeguarded by advanced electronic systems and a team of vigilant guards, making theft of this iconic artwork nearly impossible.

In an era with far less stringent security measures, on the afternoon of Tuesday, August 22, 1911, Louvre staff were stunned to find the Mona Lisa gone from its spot on the gallery wall. The museum was swiftly shut down and thoroughly searched (the painting’s empty frame was discovered on a staircase), while France’s ports and eastern borders were sealed to inspect all outgoing traffic. Despite these efforts, the painting remained missing. A frenzied investigation briefly implicated poet Guillaume Apollinaire and a young Pablo Picasso, but only wild rumors persisted: the Mona Lisa was said to be in Russia, the Bronx, or even in the possession of banker J.P. Morgan.

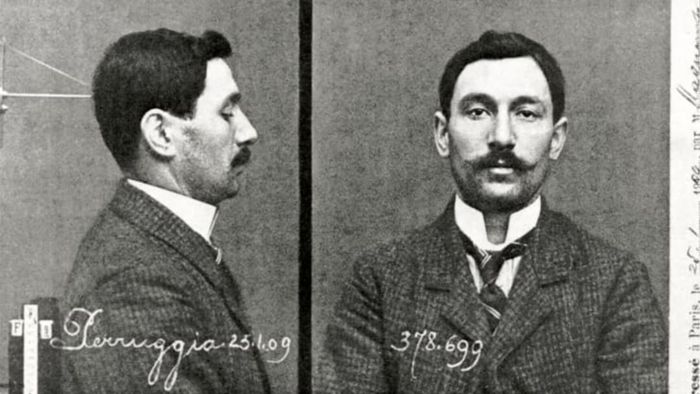

Two years after the theft, the painting was recovered when a Florentine art dealer informed the Louvre that the thief had attempted to sell it to him. The culprit was revealed to be Vincenzo Peruggia, an Italian artist who had previously worked at the Louvre on a project to encase many of the museum’s treasures in protective glass.

Vincent Peruggia | Courtesy of Chronicle Books/Alamy

Vincent Peruggia | Courtesy of Chronicle Books/AlamyAccording to reports, Peruggia confessed to the police that on the Monday morning before the theft was noticed—a day when the museum was closed—he entered the Louvre disguised as a laborer. Once inside, he made his way to the Mona Lisa, removed it from the wall and its frame, concealed it in his workman’s smock, and walked out with it under his arm. An alternative account suggests Peruggia hid in a museum closet overnight, but regardless, the theft itself was surprisingly simple and direct.

Peruggia’s motives were somewhat unclear. He claimed to the police that his intention was to return the Mona Lisa to Italy, believing it had been looted by Napoleon—whose armies were notorious for plundering art during their invasions of various countries.

Even if Peruggia genuinely believed his own narrative, his understanding of history was entirely incorrect. Leonardo da Vinci himself had brought the unfinished Mona Lisa to France in 1503 when he became the court painter for King François I. After Leonardo’s death in 1519 at a château in the Loire Valley, the painting was lawfully acquired for the royal collections.

In a 1932 article published in the Saturday Evening Post, journalist Karl Decker presented a strikingly different version of events. Decker claimed that an Argentinian swindler, who went by the name Eduardo, Marqués de Valfierno, confessed to orchestrating Peruggia’s theft of the Mona Lisa. Astonishingly, Valfierno revealed that he had sold the painting not once, but six times.

Valfierno’s scheme was intricate and involved hiring a talented forger capable of producing exact replicas of stolen artworks. In the case of the Mona Lisa, the forger meticulously recreated even the multiple layers of glaze used by Leonardo. According to Decker, Valfierno not only sold these forgeries multiple times but also used them to convince potential buyers of the authenticity of the stolen original.

The con artist would escort a victim to a public gallery and encourage them to secretly mark the back of a painting slated for theft. Later, Valfierno would present the marked canvas, claiming it had been stolen and replaced with a copy.

This deception was achieved by cleverly placing the replica behind the original painting and removing it after the buyer had made their mark. Valfierno boasted that this tactic was remarkably effective, enabling him to pre-sell the soon-to-be-stolen Mona Lisa to six different buyers in the United States, all of whom ultimately received counterfeit versions.

Museum officials display the genuine Mona Lisa upon its return to Florence’s Uffizi Gallery in 1913. | The Telegraph, Wikimedia Commons // Public Domain

Museum officials display the genuine Mona Lisa upon its return to Florence’s Uffizi Gallery in 1913. | The Telegraph, Wikimedia Commons // Public DomainThe counterfeit versions had been smuggled into the United States before the Louvre heist, when no one was suspicious. The highly publicized theft later served to authenticate these fakes, which were delivered to unsuspecting buyers in exchange for large sums of money.

Valfierno claimed that the biggest issue was Peruggia, who stole the Mona Lisa from him and returned it to Italy. When Peruggia was caught trying to sell the painting, he couldn’t expose Valfierno without undermining his own patriotic narrative, so the full scheme stayed hidden. Meanwhile, when the original Mona Lisa was restored to the Louvre, Valfierno’s buyers likely assumed they had received a replica—and were in no position to protest.

Decker’s account of Valfierno’s elaborate plot caused a sensation and quickly became the accepted explanation for the Mona Lisa’s disappearance. This is unsurprising, as Peruggia’s straightforward tale seemed too ordinary for such a legendary artwork. The more dramatic Valfierno version gained widespread belief and continues to be retold, even appearing in two recent books.

However, Decker’s Saturday Evening Post story faces several issues, including the lack of concrete evidence proving Valfierno’s existence (despite images of him being searchable online). Only Peruggia’s involvement in the Mona Lisa’s disappearance is definitively established. While it remains uncertain whether Valfierno fabricated his tale or Decker invented both the man and his account, the Mona Lisa displayed in the Louvre today is almost certainly the authentic one.