Before you settle into your seat at the cinema, a complex series of events unfolds behind the scenes. Isabel Pavia / Getty Images

Before you settle into your seat at the cinema, a complex series of events unfolds behind the scenes. Isabel Pavia / Getty ImagesEver noticed movie ads in your local newspaper announcing screenings at nearby theaters? Terms like 'Held over' or 'Special engagement' often appear. But what do they signify? And how do films travel from production studios to the big screen?

This article traces a film's journey from a mere concept to its premiere at your local theater. Discover what the 'nut' refers to, the distinction between negotiating and bidding, and the reason behind the steep price of movie theater popcorn!

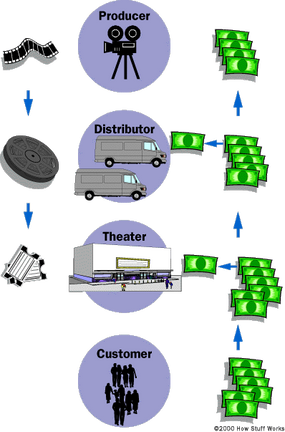

Here's the typical journey a film undergoes before reaching your local cinema:

- An individual conceives an idea for a movie.

- They draft an outline to generate interest in the concept.

- A studio or independent investor acquires the rights to the film.

- A team is assembled to produce the film, including a screenwriter, producer, director, cast, and crew.

- Once completed, the film is delivered to the studio.

- The studio enters into a licensing agreement with a distribution company.

- The distribution company decides on the number of film copies (prints) to produce.

- The company screens the movie for potential theater buyers.

- Buyers negotiate with the distributor to lease films and agree on terms.

- Prints are delivered to theaters shortly before the premiere.

- The theater screens the movie for a set period (engagement).

- Audiences purchase tickets and enjoy the film.

- After the engagement, the theater returns the print and settles the lease payment.

Certain steps may overlap, and for smaller independent films, additional processes might be required. Clearly, a significant amount of effort precedes the screening of a movie to a paying audience!

The Art of the Deal

It's often said that producing a movie is easier than securing its distribution. Given the substantial financial and time investments required for distribution, distributors need assurance of a profitable return. Support from a major studio, a renowned director, or a famous actor can significantly enhance the likelihood of a favorable distribution deal. Independent filmmakers frequently leverage film festivals to attract distributor interest. Once a distributor shows interest, both parties negotiate a distribution agreement based on one of two financial models:

- Leasing

- Profit sharing

Under the leasing model, the distributor commits to a fixed payment for the film's distribution rights. Conversely, in a profit-sharing arrangement, the distributor receives a percentage (ranging from 10 to 50 percent) of the movie's net profits. The effectiveness of each model depends on the film's box office performance. Both studios and distributors aim to forecast which model will yield the greatest advantage.

Many major studios operate their own distribution arms. For instance, Disney controls Buena Vista, a leading distributor. This setup simplifies distribution agreements and allows the parent company to retain all profits. However, the downside is the financial risk if a high-budget film fails, as there's no external party to share the loss. This risk has led to studios collaborating on major projects. For example, "Star Wars: Episode One" was produced by Lucasfilm but distributed by Fox.

After securing distribution rights, the distributor's next move is to acquire ancillary rights, enabling the film's distribution across various platforms like VHS, DVD, cable, and network TV. Additional rights may encompass soundtrack CDs, posters, games, toys, and other merchandise.

Once a movie is leased, the distributor devises an optimal opening strategy, which refers to the film's official release. Several factors influence this decision:

- Studio

- Target Audience

- Star power

- Buzz

- Season

A film with strong studio support, A-list actors, and a compelling narrative is likely to have a massive opening and perform exceptionally well. However, if a movie features big stars but lacks staying power (legs), the distributor might release it in as many theaters as possible during its initial run. Films with unknown actors or poor buzz (informal word-of-mouth) often struggle to attract theaters. Even with positive buzz, a movie targeting a niche audience or released at an unsuitable time of year may not achieve broad success. For instance, a Christmas-themed film is unlikely to thrive if released on Memorial Day weekend.

These factors influence the distributor's decision on the number of prints to produce. Each print costs between $1,500 and $2,000, so the distributor must assess how many theaters can effectively showcase the film. With 37,000 screens in the U.S., primarily in urban areas, a blockbuster might fill multiple theaters in one city, while a less popular film would draw smaller crowds. Releasing a movie on 3,000 screens could cost $6 million just for prints, so the distributor must ensure the film can attract enough viewers to justify the expense.

Theaters typically rely on buyers to negotiate with distributors. Major chains like AMC Theatres or United Artists have in-house buyers, while smaller chains and independent theaters hire external buyers. Negotiations are highly strategic, with buyers sometimes accepting less desirable films to secure highly sought-after ones. Distributors aim to balance their offerings to maintain good relationships with all local theaters. Occasionally, a theater may secure an exclusive or special engagement to debut a film in its region. Once a buyer shows interest, lease terms are negotiated.

The Need for Concessions

Theaters have two primary methods to lease a movie:

- Bidding

- Percentage

Under the bidding system, a theater commits to a fixed payment for the rights to screen a film. For instance, a theater might bid $100,000 for a four-week run of a new release. If the theater earns $125,000 during this period, it makes a $25,000 profit. However, if it only generates $75,000, the theater incurs a $25,000 loss. Bidding is now rare, as most agreements are based on a percentage of the box office revenue.

In a percentage-based deal, the distributor and theater agree on several key terms:

- The theater and distributor negotiate the house allowance, or nut, which covers weekly basic expenses.

- A percentage split is determined for the net box office, calculated after deducting the house allowance.

- A percentage split is also set for the gross box office.

- The engagement duration, typically four weeks, is agreed upon.

The distributor receives the lion's share of the movie's earnings. The contract ensures the distributor gets the higher of the agreed-upon percentages from either the net or gross box office. This arrangement is quite fascinating!

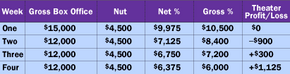

Take this scenario: Theater A is in talks with Distributor B for a new film. The theater estimates weekly expenses, or the nut, at around $4,500. The distributor's share is 95% of the net box office for the first two weeks, 90% for the third week, and 85% for the final week. Alternatively, the gross percentage is 70% for the first two weeks, 60% for the third, and 50% for the last week.

In the first three weeks, the gross percentage is more favorable, while the net percentage takes precedence in the fourth week. Thus, the distributor claims the gross percentage for weeks one through three and the net percentage for week four. The theater breaks even in the first week, incurs a loss in the second, and turns a profit in weeks three and four.

For theater owners, the movie acts as a loss leader, designed to attract audiences. The real profit comes from selling concessions like popcorn and soda. This is why refreshments are priced high—without these sales, most theaters would struggle to remain operational.

Once the agreed engagement period ends, the theater pays the distributor its portion of the box office revenue and returns the film print. If a movie remains popular and continues to draw crowds, the theater may renegotiate to extend the lease. The term "Held over" indicates that the theater has prolonged the movie's run.

Although first run films, which are newly released, serve as loss leaders, movies that have been in theaters for some time can generate profits for the cinemas screening them. Second run theaters frequently secure highly favorable leasing conditions from distributors. However, these theaters are encountering growing competition, as first run theaters increasingly extend their showings beyond the conventional four to six-week period.