Georges Méliès' 1902 masterpiece “Le Voyage Dans la Lune” showcases some of the earliest special effects in cinematic history.

© Apic/Getty Images

Georges Méliès' 1902 masterpiece “Le Voyage Dans la Lune” showcases some of the earliest special effects in cinematic history.

© Apic/Getty ImagesFrom the inception of motion pictures in the late 19th century, directors have sought innovative methods to enhance the thrill of their films. Georges Méliès, a trailblazer in filmmaking, employed various camera techniques to craft short films such as his 1898 work "Un Homme de Tête," in which his character repeatedly detaches his head and places it on a table, and his 1902 film "Le Voyage Dans la Lune," where he launched men to a moon with a pie-like face using a bullet-shaped rocket.

Animation became a medium for artists to depict imaginative tales and scenarios on screen. The era of fully animated cartoons began in 1908 with Émile Cohl, a comic strip artist, who painstakingly drew and filmed hundreds of basic illustrations to produce the short film "Fantasmagorie." This was followed by Winsor McCay's 1914 creation "Gertie the Dinosaur," which featured thousands of frames, resulting in a longer, smoother, and more lifelike animation than most of its contemporaries, which were often choppy and less refined.

Alongside the quest for innovative and fantastical effects to captivate audiences, there has been a simultaneous endeavor to achieve realism, making films more credible. This includes efforts to infuse cartoons with a greater sense of reality. Rotoscoping, a technique for animating realistic movements, emerged nearly a century ago as a solution to this challenge.

Rotoscoping involves straightforward yet labor-intensive steps and basic equipment. Essentially, it entails capturing live-action footage of actors or moving objects and meticulously tracing over each frame to produce animation. Additionally, rotoscoping is employed to achieve composite special effects in live-action films.

In certain circles, rotoscoping in cartoons is viewed negatively as a shortcut compared to traditional animation created from scratch. With the rise of computer-generated artistry, many older techniques have been replaced. Nevertheless, rotoscoping remains a valuable tool for animators and filmmakers.

The Origins of Rotoscoping

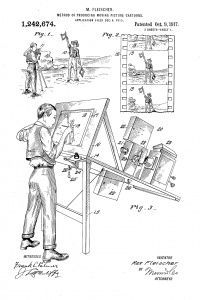

A drawing from Max Fleischer’s rotoscope patent application

U.S. Patent Office

A drawing from Max Fleischer’s rotoscope patent application

U.S. Patent OfficeMax Fleischer, an artist and technology enthusiast, conceived the idea of rotoscoping while serving as the art editor for Popular Science Monthly. His goal was to achieve smoother and more lifelike movement in animated cartoons. With the assistance of his talented brothers—Dave, Joe, Lou, and Charlie—he developed and tested the rotoscope device. Max filed a patent for the process and its associated mechanism in 1915, which was officially granted in 1917.

The rotoscoping technique began with filming live footage. For their initial attempt, the Fleischers headed to an apartment rooftop, armed with a hand-crank projector they had repurposed into a film camera. There, they captured over a minute of test footage featuring Dave dressed in a clown costume, crafted by their mother. After developing the footage, they used their makeshift rotoscope device to project the film frame by frame onto a glass panel atop an art table. Max would overlay tracing paper on the glass and sketch the still image. Once completed, he advanced the film to the next frame and repeated the process. The patent even suggested a mechanism allowing the artist to advance frames by pulling a cord.

After completing the drawings, each image had to be photographed individually. For the clown footage test, Max repurposed the projector as a camera, manually exposing each drawing to a single film frame by removing and replacing the lens cap at precise intervals. Once developed, they played the film back using the projector and confirmed the success of their method. This marked the birth of the animated clown, later named Koko.

Max continued to animate, while his brother Dave directed numerous successful cartoons, beginning with the 1919 "Out of the Inkwell" series starring Koko the Clown. Their later creations included iconic figures like Betty Boop and Popeye in the 1930s, as well as the highly realistic and costly "Superman" shorts in the 1940s. Rotoscoping was utilized to varying extents in these works, blending lifelike motion with the creative freedom and exaggeration unique to animation.

Three Betty Boop cartoons—"Minnie the Moocher," "The Old Man of the Mountain," and "Snow-White"—featured rotoscoped footage of Cab Calloway portraying different characters. The first two also opened with live-action scenes of Cab Calloway and his orchestra, with "Minnie the Moocher" containing the earliest known footage of Cab Calloway performing [source:Fleischer Studios].

Fleischer also applied the rotoscoping technique in "Gulliver's Travels," released in 1939, which became the second full-length animated feature produced in the United States.

Rotoscoping in Other Animations

A Disney animator working on a character motion sequence for “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” around 1936.

© Earl Theisen/Getty Images

A Disney animator working on a character motion sequence for “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” around 1936.

© Earl Theisen/Getty ImagesDisney's "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs" marked the first full-length animated feature in America. Prior to animation, reference footage was captured of actors performing in basic studio sets, dressed in costumes. This included young dancer Marjorie Celeste Belcher (later Marge Champion) as Snow White, dancer Louis Hightower as the Prince, comedians Eddie Collins and Billy House as Dopey and Doc, and actor Don Brodie as the disguised queen. Key frames at the start and end of character actions were rotoscoped, with animators then expanding the characters and scenery, creating the in-between frames on transparent animation cels.

The technique was also applied in "Peter Pan," using footage of actors like Hans Conried, who played both Mr. Darling and Captain Hook, Buddy Ebsen as a pirate, dancer Roland Dupree as Peter Pan, and Margaret Kerry as Tinker Bell. Rotoscoping was similarly utilized in other Disney productions.

Despite its effectiveness, rotoscoping faced criticism. Some viewed it as a shortcut, while others noted discrepancies in the appearance and movement of rotoscoped characters compared to traditionally animated ones, such as animals. Disney even attempted to downplay its use in "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs," seating Marjorie Belcher away from the audience at the premiere and instructing her not to discuss her involvement. Belcher only learned decades later, during a Disney exhibit, that her footage had been rotoscoped. Regardless of the methods, the film remains an animation masterpiece and a timeless classic.

The technique continued to be widely used in animation long after its inception. Some films relied heavily on rotoscoping, creating visuals that resembled painted film footage. The "Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds" sequence in the

A-Ha's 1985 music video for "Take On Me" famously employed rotoscoping, blending live-action footage with sketchy comic book-style animation. That same year, the technique was used in INXS's "What You Need" video to incorporate animated and colorful effects.

In more recent years, Richard Linklater's films "Waking Life" (2001) and "A Scanner Darkly" (2006) were created by filming live actors and transforming the footage into animation through interpolated rotoscoping. While numerous animators contributed, the process was expedited using software developed by MIT graduate Bob Sabiston, which interpolated frames between key rotoscoped images to achieve smooth results.

Rotoscoping is also a valuable tool for animators learning to create motion from scratch. Beyond animation, it plays a significant role in live-action films as well.

Old School Rotoscoping of Special Effects

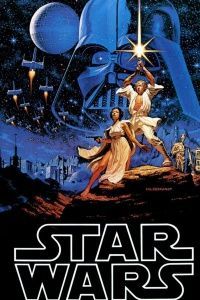

The iconic lightsaber blades in the “Star Wars” films were created using rotoscoping techniques.

© Universal History Archive/UIG via Getty images

The iconic lightsaber blades in the “Star Wars” films were created using rotoscoping techniques.

© Universal History Archive/UIG via Getty imagesRotoscoping extends beyond animation, having been employed to enhance Alfred Hitchcock's 1963 movie "The Birds," integrate lightsaber effects into the original "Star Wars" trilogy, and add visual effects to numerous other films.

During the era of physical film editing, rotoscoping was utilized to paint special effects onto animation cells layered over live-action footage. It also served to create mattes (or masks), enabling filmmakers to merge elements from different scenes. For instance, a director might overlay footage of an actor on a soundstage with a background like the ocean, outer space, or an explosion. This process of combining separate images or effects into a single frame is known as compositing.

This type of rotoscoping was an arduous and time-intensive process. Similar to its animation counterpart, it required projecting each film frame onto a glass plate and meticulously tracing elements frame by frame. Special effects artists or animators would trace the necessary components onto transparent cells, which were then painted to form mattes. These mattes were placed over another frame (such as a background shot) to block out specific areas, creating space for foreground effects.

The procedure often involved multiple film reels, including the original foreground and background shots, blacked-out mattes, and negative versions of the mattes with blacked-out backgrounds. A new film reel would be exposed multiple times to merge all elements. The background image was exposed with the black matte in place, while the foreground element was exposed using the negative matte, ensuring the foreground appeared in the designated area. This method allowed rotoscoped mattes to seamlessly combine foreground and background elements in each film frame.

Achieving precision required immense effort. Standard 35mm film runs at 24 frames per second, equating to 1,440 frames per minute. This meant mattes had to be painted for dozens, hundreds, or even thousands of frames. In action sequences, moving objects shift slightly in each frame, necessitating traveling mattes that adjust position and shape. The complexity increases when multiple elements interact or overlap on screen, requiring several mattes per frame.

The process demanded meticulous attention to detail. Each frame required precise outlines and painted mattes, consistent lighting (or post-production color correction), and perfect alignment of physical elements like mattes, film, and equipment. Any misalignment would result in unnatural movement or visual inconsistencies.

When executed skillfully, rotoscoping could depict scenes that were challenging or impossible to film in reality. It also served practical purposes, such as removing unwanted objects like cables, microphones, staging markers, or other items accidentally or intentionally left in the shot, which could distract viewers and disrupt immersion.

While the technique is still in use today, modern advancements in rotoscoping, matte creation, and compositing have streamlined the process in the digital era.

New Rotoscoping Tools

The advent of smaller, more affordable, and powerful computers has ushered in a transformative era in filmmaking. CGI (computer-generated imagery) enables filmmakers to create nearly anything on screen with a high degree of realism. Alongside other special effects techniques (some of which we'll explore later), advanced graphics software has introduced more efficient rotoscoping methods, significantly reducing the time required compared to traditional physical film techniques.

While the core concepts remain similar, the tools and media have largely shifted to digital formats, including digital film, virtual paint, and software. Instead of using physical animation cels and glass tables, modern graphics software allows artists to work with virtual layers. One layer contains the digitized film image, while others hold the animations or effects for each frame. The final product is saved or exported as a digital file, eliminating the need for physical photography.

Graphics software enables many of the same tasks previously done with physical film and equipment. Artists can paint over digitized video frames using a mouse, trackpad, or graphics tablet to create traditional rotoscoped animations. They can choose to retain the original film alongside the animation or remove the film entirely, leaving only the animated elements. Additionally, complex mattes can be crafted to composite live-action or computer-generated objects into each frame.

Mattes can be created frame by frame using selection and paint tools within the software. Splines—lines or curves adjustable by dragging points—make it easier to modify mattes across frames without redrawing them entirely. Some software can even automate tasks across multiple frames, using keyframes to generate intermediate frames. Advanced tracking features allow the software to follow the movement of objects, ensuring composited elements align correctly. Modern tools excel at recognizing and masking shapes across frames, drastically reducing the need for manual tracing and saving significant time.

Contemporary graphics software also simplifies tasks like color adjustments, morphing objects, blurring edges, and cloning parts of an image. The cloning tool is particularly useful for removing unwanted elements like cables or boom mics, seamlessly replacing them with background details such as walls or skies to make it appear as though they were never present.

The 1990s saw the emergence of early software tools for rotoscoping and similar techniques, including Colorburst, Commotion, and Matador. Today, a variety of modern software supports rotoscoping at different levels, such as Adobe Flash, Adobe Photoshop, Adobe After Effects, Imagineer Systems' Mocha, Silhouette, Autodesk's Flame and Smoke, Blackmagic's Fusion, and Foundry's Nuke, Ocula, and Mari. While some of these tools are costly and demand high-performance, expensive hardware, others like Adobe Flash and After Effects are accessible to hobbyists and independent filmmakers.

Color Keying Versus Rotoscoping

Actor Peter Capaldi performing in front of a screen during the filming of an episode of “Doctor Who.”

© Matthew Horwood/GC Images

Actor Peter Capaldi performing in front of a screen during the filming of an episode of “Doctor Who.”

© Matthew Horwood/GC ImagesColor keying, also known as chroma keying, is a popular alternative to rotoscoping for compositing special effects. Often referred to by the background color used during filming (such as blue screen or green screen), this technique dates back to 1940 when it was first employed in the film "The Thief of Bagdad."

Disney developed its own version of this technique, filming actors against a white background illuminated by sodium vapor lamps. This proprietary method was used to composite effects in films like "The Parent Trap," "The Absentminded Professor," and "Mary Poppins."

Green became the preferred backdrop over blue as post-production shifted to digital, as it is easier to light and digital cameras capture more detail against it. Regardless of the color, color keying automates the creation of traveling mattes by filming actors and foreground elements against a solid-colored background. The color is then removed digitally or through film processing to isolate foreground and background elements. This eliminates the need for manual frame-by-frame outlining, though it introduces challenges like ensuring actors avoid wearing the backdrop color and addressing color spill that may require correction.

Color keying isn't flawless. Rotoscoping is often employed to correct on-set errors, such as when a subject moves outside the color screen area. For example, if an actor's arm extends beyond the screen, rotoscoping can create a traveling matte for the out-of-bounds section, ensuring proper compositing.

Motion Capture Versus Rotoscoping

A performer wearing a motion-capture suit has their movements digitally translated into a screen character.

© ADRIAN DENNIS/AFP/Getty Images

A performer wearing a motion-capture suit has their movements digitally translated into a screen character.

© ADRIAN DENNIS/AFP/Getty ImagesMotion capture, or mocap, is a newer technique similar to rotoscoping and color keying, used to integrate moving elements, particularly actors, into scenes. Like traditional rotoscoping, it enhances characters with realistic motion and appearance. However, mocap, a product of the digital era, delivers unparalleled realism in graphics and movement compared to earlier methods.

Initially developed for motion analysis, this technique has been utilized in films and video games since the mid-1990s. It involves digitally recording the movements of live actors to generate a 3-D computer model of their bodies and actions. Early versions required actors to wear suits adorned with reflective markers or sensors, performing on a soundstage surrounded by cameras. The captured data was then processed by software to create a dynamic 3-D model of the performance. Animators and effects specialists later added facial expressions, costumes, and other details using graphics software. This method was employed for scenes in "Batman Forever" (1995), crowd sequences in "Titanic" (1996), Jar Jar Binks in "Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace" (1999), and Gollum, portrayed by Andy Serkis, in "The Fellowship of the Ring" (2002).

Each major motion capture project introduces advancements that refine the process. A significant leap was facial performance capture, first used for the titular character in Peter Jackson's "King Kong" (2005), Davy Jones in "Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man's Chest" (2006), and the Na'Vi in James Cameron's "Avatar" (2009). Initially, this involved facial sensors or markers, but "Avatar" introduced helmets with cameras positioned in front of the actors' faces, capturing detailed facial movements. This data was used to infuse CGI characters with the actors' authentic performances, reducing reliance on post-production animation. Actors performed on set wearing these helmets and LED-equipped suits, interacting with each other while being filmed by Weta's "The Volume" system.

Another milestone was achieved in "Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man's Chest" (2006), where Bill Nighy performed alongside other actors in a marker-covered suit. Industrial Light and Magic later added CGI elements for Davy Jones using the on-set data. In "Rise of the Planet of the Apes" (2011) and "Dawn of the Planet of the Apes" (2014), both featuring Andy Serkis, performance capture was conducted outdoors using suits with infrared LEDs and helmet-mounted cameras.

A groundbreaking innovation debuted in "Avatar," where a virtual camera with a monitor allowed James Cameron to view actors as their CGI characters in real-time, alongside the digital environment. This technology was also used in Peter Jackson's "The Hobbit" trilogy. While the final, highly realistic results still require extensive post-production, this tool enhances on-set visualization and direction. Future advancements promise even more seamless real-time graphics.

Motion capture has also been used to produce fully animated films like "Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within" (2001), Robert Zemeckis's "The Polar Express" (2004), and "Beowulf" (2007). While the first two faced criticism for characters falling into the "Uncanny Valley," newer animations have largely overcome these issues with improved realism.

The Present and Future of Rotoscoping

Directors James Cameron and Peter Jackson are likely to remain at the forefront of advancing special effects in filmmaking.

© Kevin Winter/Getty Images

Directors James Cameron and Peter Jackson are likely to remain at the forefront of advancing special effects in filmmaking.

© Kevin Winter/Getty ImagesBoth rotoscoping and motion capture enable an actor's performance to shine through in a graphically rendered character, not just in voice. Performance capture, however, can transform an actor into any creature the story demands, eliminating the need for extensive makeup and costumes while delivering lifelike appearance and movement.

Despite its potential, performance capture is costly and not always essential for storytelling. While nearly every film employs subtle effects—like removing a boom mic, simulating nighttime scenes, or adding snow to a spring shoot—not all require fully CGI characters.

These techniques provide animators and filmmakers with tools to craft visually stunning and imaginative scenes. In live-action films, they enable the creation of sequences that would be impractical, hazardous, or impossible to film in real-world settings. Advances in digital tools are making it easier and more affordable to achieve unprecedented levels of realism.

Even with the advent of advanced technologies, rotoscoping remains a valuable tool for filmmakers and graphic artists. It can be employed to achieve a specific aesthetic, as seen in Richard Linklater's "Waking Life" and "A Scanner Darkly." Additionally, it serves as a reliable solution for correcting filming errors and meeting various post-production compositing requirements.