In July 1939, Ian Fleming was assigned as an aide to Admiral John Godfrey, the head of Britain’s naval intelligence (and a potential model for James Bond’s MI6 superior, M). Godfrey had a passion for fly-fishing, while Fleming was an avid fan of fiction. Shortly after World War II began, they combined their interests to create the Trout Memo—a classified document outlining deceptive strategies that compared espionage to the art of fishing.

The 28th entry among roughly 50 proposals in the memo, described as “rather unpleasant,” was inspired by a 1937 mystery novel by ex-intelligence officer Basil Thomson. In The Milliner’s Hat Mystery, a deceased man is discovered carrying fabricated papers that hide his real identity. As outlined in the Trout Memo, “a body dressed as an airman, carrying misleading dispatches, could be deposited on the European coastline,” where the false information might be intercepted by German forces.

What initially seemed like the memo’s most improbable suggestion eventually evolved into a mission that deceived the most formidable target of all—Adolf Hitler—and significantly aided the crucial Allied assault on Sicily in July 1943.

Historian Ben Macintyre detailed the entire tale in his 2010 book Operation Mincemeat, which serves as the foundation for Netflix’s latest film bearing the same title. Dive into the captivating true story of the operation and the daring team behind its success.

Note: Minor spoilers for Netflix's Operation Mincemeat follow. Additionally, some historic images may be unsettling to certain viewers.

A Clever Plan

Roosevelt and Churchill in Morocco at the Casablanca Conference. | U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, Wikimedia Commons // Public Domain

Roosevelt and Churchill in Morocco at the Casablanca Conference. | U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, Wikimedia Commons // Public DomainBy early 1943, Britain was concluding its North African campaigns and shifting focus to the Mediterranean, with the goal of weakening Italy. During the Casablanca Conference in January, Winston Churchill and Franklin D. Roosevelt concurred that Sicily was the optimal entry point. However, this choice was so predictable that Germany and Italy were likely to reinforce the island heavily, ready to confront Allied forces.

Instead of opting for a less strategic route, the Allies chose to deceive Germany into believing their true targets were Greece and Sardinia. This grand deception involved a series of elaborate ruses. Under the codename “Operation Barclay,” British intelligence recruited Greek interpreters, amassed Greek currency, and fabricated the entirely fictitious Twelfth Army to “position” near Greece—all while ensuring German spies were aware of these activities.

Operation Mincemeat was loosely tied to Barclay, though it wasn’t initially tied to the Sicilian invasion when Charles Cholmondeley (portrayed by Succession star Matthew Macfadyen) first proposed it in October 1942. Cholmondeley, a lanky 25-year-old with an impressive mustache, had lost his brother at Dunkirk. Initially a Royal Air Force lieutenant disqualified from flying due to poor eyesight, he had since become an MI5 agent and secretary of the Twenty Committee—a group overseeing double agents. (The name referred to the Roman numeral XX, symbolizing the ‘double-cross’ nature of their work.)

Cholmondeley presented his idea, inspired by the Trout Memo and dubbed “Operation Trojan Horse,” to the Twenty Committee. He may have also been influenced by a recent event where real Allied officers crashed off the Spanish coast, leading to sensitive information falling into Nazi hands.

(Left) Ewen Montagu and Charles Cholmondeley. | David Stubblebine, World War II Database // Public Domain

(Left) Ewen Montagu and Charles Cholmondeley. | David Stubblebine, World War II Database // Public DomainJohn Masterman, the committee leader and a novelist himself, approved Cholmondeley’s unusual plan and assigned Montagu as his co-leader. Montagu, a 42-year-old seasoned lawyer, represented the Naval Intelligence Division on the committee, having worked under Godfrey during the war. (Years later, Montagu would characterize his superior as “the world’s biggest jerk, but a brilliant one.”)

With the green light given, the search for the ideal cadaver began.

Guide to the Corpse

Bentley Purchase (Paul Ritter) delivers the body of Glyndwr Michael (Lorne MacFadyen) to Cholmondeley and Montagu. | Giles Keyte/Netflix

Bentley Purchase (Paul Ritter) delivers the body of Glyndwr Michael (Lorne MacFadyen) to Cholmondeley and Montagu. | Giles Keyte/NetflixSince their fake airman would undoubtedly undergo an autopsy, Montagu sought advice from renowned forensic pathologist Bernard Spilsbury on plausible causes of death other than drowning. Spilsbury assured him that plane crashes could result in fatalities through various means, including shock. Montagu then reached out to an old friend, Bentley Purchase, the coroner at St. Pancras Hospital, who had access to numerous cadavers.

Purchase began searching for an appropriate body and promptly informed Montagu when 34-year-old Glyndwr Michael died at St. Pancras on January 28. Michael, a Welshman, had been found near death in an abandoned warehouse two days earlier. He had ingested rat poison, either intentionally or accidentally through contaminated food. Spilsbury and Purchase agreed that the poison would likely remain undetected during an autopsy after the body had been submerged in water for an extended period.

Additionally, Michael, who had a history of mental illness and hospitalizations, appeared to have no fixed address or close relatives who might inquire about him. (He did have a few siblings, but the Mincemeat team couldn’t locate them at the time. Contrary to the film, there’s no record of a sister attempting to claim his body during the operation.)

Purchase also provided a crucial timeline for the mission. Freezing the corpse entirely would raise suspicions during an autopsy, so Montagu and Cholmondeley had roughly three months to execute their plan before decomposition became too advanced.

Before proceeding, they needed to replace Trojan Horse with a name from the list of approved military operation titles. Montagu found Mincemeat too fitting to ignore. “By this point, my sense of humor had turned somewhat dark, and the word seemed like a good omen,” he wrote in his 1953 book The Man Who Never Was.

On February 4, the duo presented a formal proposal to the Twenty Committee. Operation Mincemeat, they explained, could deceive Germany into believing Sicily was a diversion for a real attack on Greece—rather than the primary target. The committee approved the plan and quickly began coordinating with all relevant parties. The War Office, for instance, would need to produce fake identification documents, while the Admiralty would identify a suitable coastal location to deposit the body.

Over the following months, Glyndwr Michael vanished entirely—and Major William “Bill” Martin of the Royal Marines was born from nothing.

The Pam Behind Their Bill

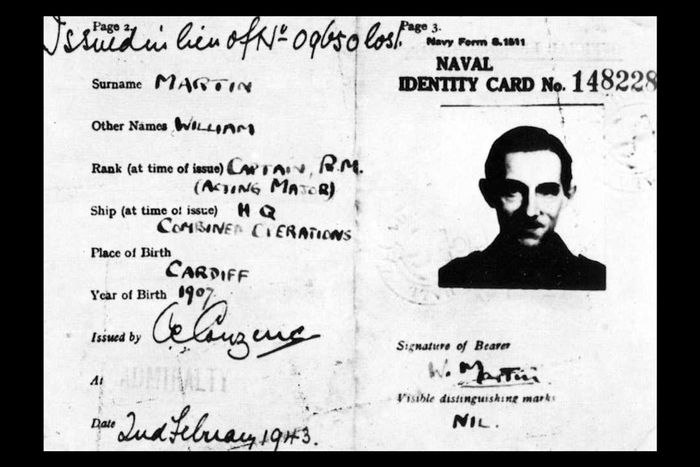

William Martin's ID card featuring Ronnie Reed's photograph. | Ewen Montagu Team, Wikimedia Commons // Public Domain

William Martin's ID card featuring Ronnie Reed's photograph. | Ewen Montagu Team, Wikimedia Commons // Public DomainA William Martin in the Royal Marines already existed, and this was no accident. Montagu and Cholmondeley selected the name in case German officials cross-referenced it with a Royal Marines list. The actual Martin was far from the spotlight, training U.S. pilots in Rhode Island.

However, convincing Germany that Major Martin wasn’t a fabrication required more than just a well-chosen name. For instance, they needed a photo for Martin’s ID—but Michael’s corpse appeared unnaturally pale in pictures. After weeks of searching for someone who resembled Michael, Montagu found Ronnie Reed, a BBC radio engineer working part-time for MI5. With minor adjustments, Reed could pass as Michael, and he agreed to pose for the ID photo. To ensure Martin’s uniform looked worn, Cholmondeley, who had a similar build to Michael, wore it regularly.

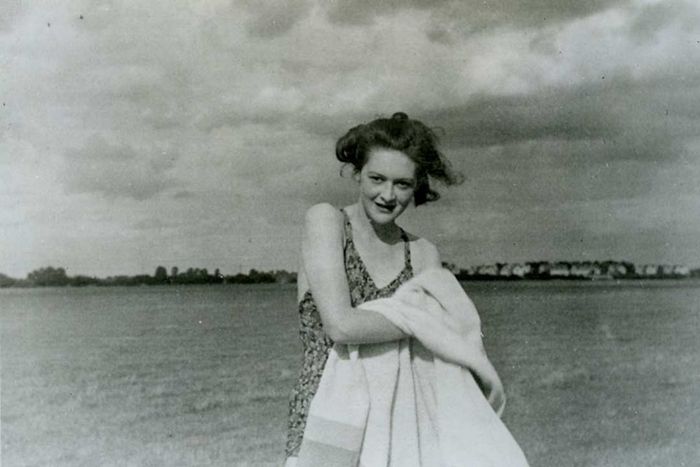

Joan Saunders, Montagu’s colleague in the NID, suggested creating a fictional love interest for the doomed Marine. Montagu then asked the young women in the office to provide photos of themselves to serve as “Pam.” He personally approached Jean Leslie, a striking 20-year-old from the MI5 secretarial pool. Unlike her film counterpart, played by Kelly Macdonald, Leslie wasn’t a widow; the photo she submitted had been taken just weeks earlier on a date.

Jean Leslie, also known as "Pam." | The National Archives, Wikimedia Commons // Public Domain

Jean Leslie, also known as "Pam." | The National Archives, Wikimedia Commons // Public DomainMontagu not only selected her photo for the mission but also immersed himself so deeply in the roles of Bill and Pam that their connection evolved into a genuine (if perhaps platonic) romance. He wrote her numerous letters as “Bill,” and they frequently spent time together outside work. Montagu was transparent about this in his letters to his wife, Iris, who was staying in the U.S. with their two children. (Given their Jewish heritage, relocating abroad seemed the safest option.)

“I took a girl from the office to Hungaria [a restaurant] for dinner and dancing. She’s quite charming,” he wrote in one letter, the first of many where Leslie is referenced (though not by name).

Montagu’s affection for Leslie doesn’t seem to have stemmed from a lack of love for his wife. His letters to Iris were filled with heartfelt expressions like “I miss you terribly” and “How incredibly happy we were before this wretched war began … Damn Hitler.” Additionally, there’s no indication that his bond with Leslie caused friction with Cholmondeley, who, in the film, awkwardly vies for her attention.

The filmmakers of Operation Mincemeat took creative liberties with another potential source of tension between Montagu and Cholmondeley. Montagu’s brother Ivor did indeed support Russian communists for years, even forming a friendship with Leon Trotsky. However, while MI5 closely monitored Ivor’s activities, there’s no evidence that Cholmondeley was assigned to investigate Ewen during their collaboration on Operation Mincemeat.

Body of Lies

Some of Major Martin's personal items. | David Stubblebine, World War II Database // Public Domain

Some of Major Martin's personal items. | David Stubblebine, World War II Database // Public DomainThe Mincemeat team dedicated significant effort to crafting a detailed backstory for Martin, which guided the selection of items to place in his pockets. They envisioned him as a fun-loving, somewhat extravagant man from a wealthy Roman Catholic family in Wales. He enjoyed fishing, loved the theater, and had a niece named Priscilla. Among his belongings, they included a St. Christopher’s medal, a cross necklace, a stamp booklet, an invitation to the Cabaret Club, a pack of cigarettes, and a letter from his stoic father. Additionally, they added tokens of his relationship with Pam: a heartfelt letter (composed by Leslie’s boss, Hester Leggett), her photograph, and a receipt for an engagement ring.

The crowning touch was a letter from General Archibald Nye to General Harold Alexander, who served under General Dwight D. Eisenhower in Tunisia. This personal note—rather than an official communication—subtly referenced the Sicily diversion and the planned invasion of Greece.

In the movie, a frustrated Montagu drafts multiple versions of the letter, which are incessantly scrutinized by Godfrey, depicted as the primary supervisor of Mincemeat. In reality, Commodore Edmund Rushbrooke took over as NID’s director during the operation, and it was Colonel Johnnie Bevan, leader of the ultra-secret London Controlling Section, who critiqued Montagu’s wording. Ultimately, Montagu asked Nye to write the letter himself, which he did.

Cholmondeley (left) and Montagu pictured with the truck that would carry Major Martin to the submarine. | The Times, Wikimedia Commons // Public Domain

Cholmondeley (left) and Montagu pictured with the truck that would carry Major Martin to the submarine. | The Times, Wikimedia Commons // Public DomainFollowing advice from Britain’s naval attaché in Madrid, Salvador Augustus Gómez-Beare, Montagu and Cholmondeley chose to place Martin off the coast of Huelva, a fishing town in southwestern Spain with strong German ties. Cholmondeley abandoned the idea of dropping the body from a plane, opting instead for a submarine launch to ensure its preservation. To protect the corpse during transit, he hired engineer Charles Fraser-Smith—often considered the model for Q in Fleming’s Bond series—to create an airtight steel coffin filled with dry ice.

“All the details are now finalized,” Montagu wrote in a March 26 letter to Bevan, who soon secured approval from both Churchill and Eisenhower. Montagu and Cholmondeley then escorted Major William Martin to Scotland, where, on April 19, he departed aboard the HMS Seraph.

Read Letter Day

The body of Glyndwr Michael just before being sealed in the transport coffin. | The National Archives, Wikimedia Commons // Public Domain

The body of Glyndwr Michael just before being sealed in the transport coffin. | The National Archives, Wikimedia Commons // Public DomainThe crew of the Seraph set Martin adrift in the ocean before dawn on April 30. That same morning, Spanish fishermen discovered him and handed him over to the authorities. Fortunately, the local coroner, possibly swayed by the intensifying odor as the day warmed, determined that Martin had drowned without conducting an extensive examination.

Ensuring that German spies in the area intercepted Nye’s letter—along with other fabricated documents in Martin’s briefcase—proved more challenging. Martin’s possessions had been handed to the Spanish Navy, which was far more meticulous than some German-sympathizing local officials. To prompt the Nazis to seek out the letters, Montagu and Cholmondeley engaged in a correspondence with Captain Alan Hillgarth, a British naval attaché in Madrid (and one of many potential inspirations for James Bond), emphasizing that Martin’s briefcase contained highly classified information that needed to be returned promptly. They anticipated that the Nazis would intercept these communications, and they were correct.

The Abwehr, Germany’s intelligence agency, became increasingly eager to get their hands on the briefcase. However, it took almost 10 days for it to reach a Spanish official in Madrid who allowed the Germans to photocopy its contents. From that point, events unfolded rapidly.

Alexis von Roenne, leader of the Nazi intelligence agency Fremde Heere West (Foreign Armies West), wrote a report asserting that “The circumstances of the discovery, along with the format and content of the dispatches, provide undeniable proof of the letters’ authenticity.” Some historians suggest von Roenne’s lack of skepticism indicates he might have been covertly opposing the Nazis; he was, after all, later executed for his involvement in the July 1944 plot to assassinate Hitler (which von Roenne supported). Whether genuine or not, his confident endorsement likely influenced Hitler—who deeply trusted him—to accept the letters as legitimate.

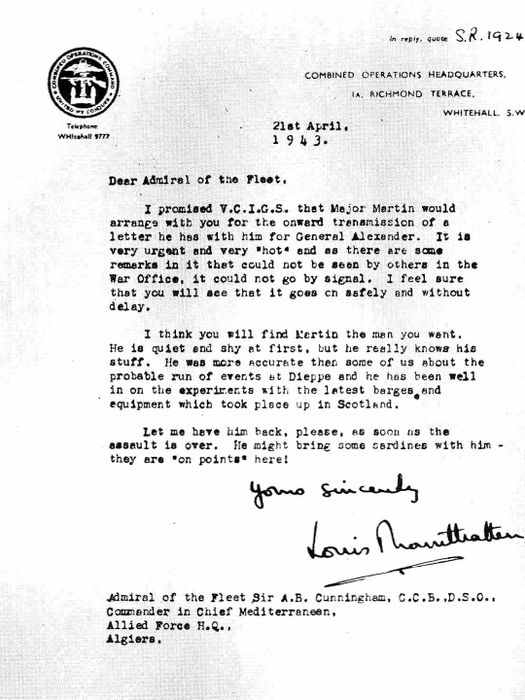

A letter in Martin's case from Louis Mountbatten (Prince Philip's uncle). | David Stubblebine, World War II Database // Public Domain

A letter in Martin's case from Louis Mountbatten (Prince Philip's uncle). | David Stubblebine, World War II Database // Public DomainThroughout May, British intelligence gathered multiple signs that Hitler and his top officials were convinced the Allies would attack Greece and Sardinia, and were preparing defenses accordingly. Meanwhile, Montagu and Cholmondeley retrieved Martin’s briefcase from the Spanish Navy. Although the letters’ seals remained intact, analysts determined that the envelope flaps had been tampered with just enough to insert a thin rod, wrap the letter around it, and pull it out. An eyelash hidden in one of the folded letters was also gone.

By this stage, Operation Mincemeat had largely achieved its objectives. The success of the invasion of Sicily—codenamed Operation Husky—would soon be put to the test.

Outsmarted and Outmaneuvered

Allied forces storm the shores of Sicily during the launch of Operation Husky. | Hulton Archive/GettyImages

Allied forces storm the shores of Sicily during the launch of Operation Husky. | Hulton Archive/GettyImagesIn the early hours of July 10, British, American, and Canadian troops began arriving en masse on Sicily’s southern coastline. Germany had only two divisions stationed on the island at the time. Despite the reinforcements that later arrived—alongside Italy’s own troops—the Axis forces were overwhelmed by the Allies’ approximately 150,000 soldiers, 3000 ships, and 4000 aircraft. By mid-August, the Allies had secured the entire island, forcing the Germans and Italians to retreat to mainland Italy.

Operation Husky marked the downfall of Italy’s alliance with the Axis. Within just two weeks of the invasion, Benito Mussolini’s government collapsed, and the new administration began negotiating peace with the Allies. On September 8, Italy officially capitulated (though the subsequent German occupation delayed the country’s transition to peace).

It’s difficult to predict how these events might have transpired without Operation Mincemeat. Notably, it wasn’t the sole strategy employed to divert Nazi attention from Italy. Hitler’s anxiety about losing the Balkans—a vital source of wartime resources for Germany—already had him concerned about an Allied invasion through Greece. At the very least, Operation Mincemeat reinforced Hitler’s inclination toward a decision he was already leaning toward, and it is frequently cited as a pivotal element in the triumph of Operation Husky.

Operation Mincemeat is now available for streaming on Netflix.