Pastor Mack Wolford, a follower of the Pentecostal 'Signs Following' movement, was photographed handling a rattlesnake during a service at the Church of the Lord Jesus in Jolo, West Virginia, on September 2, 2011. Tragically, Wolford passed away the following year after being bitten by a rattlesnake.

Lauren Pond For The Washington Post via Getty Images

Pastor Mack Wolford, a follower of the Pentecostal 'Signs Following' movement, was photographed handling a rattlesnake during a service at the Church of the Lord Jesus in Jolo, West Virginia, on September 2, 2011. Tragically, Wolford passed away the following year after being bitten by a rattlesnake.

Lauren Pond For The Washington Post via Getty ImagesBefore his death, Pastor Jamie Coots had survived nine snake bites [source: Burnett]. For over 20 years, he handled venomous snakes at his church in Kentucky, one of the roughly 100 congregations in the U.S. that practice "holiness serpent handling" in the modern era [sources: Burnett, Lewis, Wilking and Effron]. Coots gained some fame through his appearance on National Geographic's 2013 reality series "Snake Salvation," standing out in a community that typically avoids the spotlight [sources: Burnett, Estep].

Coots' fatal rattlesnake bite in 2014 drew significant media attention, highlighting the public's ongoing intrigue with religious snake handling. The practice is both daring and captivating. However, it's not limited to religious contexts.

Researchers extract venom from snakes to create life-saving anti-venom or study phenomena like the force exerted by constrictors when subduing prey [source: Moon and Mehta]. Veterinarians specializing in snakes often insert feeding tubes into conscious reptiles [source: Pet Place]. Additionally, snake removal experts are called in when situations arise, such as discovering a 14-foot (4-meter) python in a backyard shed.

While not all snakes pose a threat to humans, with most being relatively harmless, especially to larger beings like people [source: Wexo], those that are dangerous can cause severe harm. Venomous snakes deliver toxins through their fangs, leading to symptoms such as intense pain, swelling, paralysis, tissue damage, and even organ failure [sources: Barish and Arnold, MedlinePlus]. Constrictors, on the other hand, strike and wrap around their prey, using their powerful coils to suffocate or crush their victims, often resulting in cardiac arrest or spinal injury [source: Team].

Handling snakes capable of killing or injuring a human requires a unique mindset, whether for professional or religious purposes. Such individuals are often fearless, risk-tolerant, and unbothered by the presence of snakes. However, professionals and religious practitioners differ significantly in their methods, with professionals prioritizing safety and survival for all parties involved.

Where Caution Reigns: Professional Snake Handling

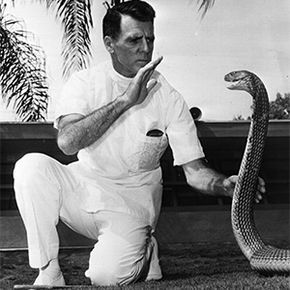

In 1972, renowned snake handler Bill Haast was photographed interacting closely with a cobra.

Alan Band/Fox Photos/Getty Images

In 1972, renowned snake handler Bill Haast was photographed interacting closely with a cobra.

Alan Band/Fox Photos/Getty ImagesHandling snakes safely and humanely is a skill that requires extensive training. It involves more than just preventing bites; it demands a deep understanding of snake behavior and biology.

Herpetologists, specialists in the study of amphibians and reptiles, usually hold advanced degrees in biological sciences and undergo additional training focused on reptiles [source: SSAR]. Snake removal experts, often referred to as "rescue and relocation" professionals, are skilled in identifying, understanding the behavior of, and safely managing snakes across various environments [source: Animal Ark].

The level of expertise among snake "displayers"—individuals who perform at attractions or conduct interactive demonstrations—varies widely. While not all states impose regulations on this field, many displayers have extensive experience, sometimes spanning decades, and some are even trained herpetologists [sources: MacGuill, Schudel, Klinkenberg].

Professional snake handlers prioritize safety for both humans and snakes, often relying on specialized tools to minimize risk [source: Hunter]. Common equipment includes snake hooks and tongs, which keep venomous snakes at a safe distance during handling or display. Veterinarians may use soft, clear tubes to secure a snake's head or mesh panels to restrain the entire body during examinations or treatments [sources: Hunter, Snake Getters]. Zookeepers, meanwhile, use feeding tongs to deliver meals to snakes [source: The Cincinnati Zoo and Botanical Garden].

The process of milking snakes, however, necessitates free-handling: manually holding the snake without tools. The milker grips the snake's head near the jaw hinge with their thumb and index finger, immobilizing it and positioning their fingers over the venom glands. By applying pressure to the jaw, the snake's mouth is forced open, and its fangs are guided through a latex-covered jar. Venom extraction is then initiated by massaging the glands [sources: Reptile World Florida, ZME Science].

During milking, it is essential to have at least two handlers present [source: WHO]. Having backup is a wise practice in any snake-handling scenario. This ensures someone can call for emergency assistance, transport an injured person to a hospital with anti-venom, or manage a situation like restraining a Burmese python's tail while waiting for additional help [source: Stein].

For handling constrictors, experts advise having one handler for every 5 feet (1.5 meters) of snake length, and one handler for every 3 feet (1 meter) when dealing with anacondas or reticulated pythons [source: Flank].

In professional snake handling, safety is the top priority. However, for those who handle snakes as part of religious practices, caution is not the primary focus. Beyond the presence of snakes, the two approaches—professional and religious—are starkly different.

Bill Haast, known as "Snakeman," passed away in 2011 at the age of 100, leaving behind a remarkable legacy. While he entertained tourists at his Miami Serpentarium, his true contribution was in the field of venom research. Despite lacking formal scientific training, Haast became the leading supplier of medical venom in the U.S., extracting venom from species like king cobras, diamondback rattlesnakes, green mambas, and blue kraits [sources: Schudel, Hunter]. His work led to the first anti-venom for coral snake bites after 69,000 milkings [source: Miami Serpentarium Laboratories]. Haast also developed a personal immunity by injecting small doses of venom daily, and his blood transfusions saved over 20 lives [source: Wells, Schudel]. In the 1970s, he collaborated on venom-based treatments for diseases like multiple sclerosis and Parkinson's, though these were later banned by the FDA [source: Schudel].

A Matter of Faith: Holiness Serpent Handling

In 1945, Lewis Ford was photographed placing a rattlesnake around the neck of a Tennessee congregation member. Tragically, Ford died later that year from a snake bite.

© Bettmann/Corbis

In 1945, Lewis Ford was photographed placing a rattlesnake around the neck of a Tennessee congregation member. Tragically, Ford died later that year from a snake bite.

© Bettmann/CorbisThe practice of holiness serpent handling is widely believed to have originated in the early 20th century in Tennessee, attributed to a preacher named George Hensley. According to legend, Hensley, during a crisis of faith, was reflecting on a verse from the Gospel of Mark—"They shall take up serpents; and if they drink any deadly thing, it shall not hurt them" (Mark 16:18)—when he encountered a venomous snake. Feeling compelled to pick it up, he emerged unharmed, solidifying his faith [sources: Phillips, Mariani].

Hensley interpreted the biblical command literally and preached that true obedience to God, and thus salvation, required believers to "take up serpents" [source: Loller]. Followers of this movement also consume strychnine, another "deadly thing" mentioned in the scripture [source: Mariani].

By the 1930s, serpent handling had gained significant traction in Appalachia. Despite increasing practitioner fatalities leading to its prohibition by the 1940s, the practice persisted [source: Scott].

Practitioners, who prefer the term "serpent" over "snake," are members of various evangelical churches within the Pentecostal tradition, particularly the Church of God with Signs Following [source: Lewis]. They handle snakes without tools or safety measures, relying solely on their faith [sources: Handwerk].

Videos depict practitioners holding rattlesnakes and copperheads—commonly kept by churches—within striking distance, without immobilizing the snakes' heads. Jamie Coots, for instance, was known to interact closely with snakes [source: Mariani]. Techniques include lifting snakes into the air, draping them over shoulders, and handling multiple snakes simultaneously, often in a state of ecstatic trance [sources: CNN].

The experience of serpent handling has been described as profoundly peaceful and euphoric, surpassing the intensity of any drug-induced high [sources: Loller, Burnett].

Today, several thousand individuals follow the practice of serpent handling, though not all actively handle snakes [sources: Lewis, Wilking and Effron]. The act of taking up serpents is seen as obedience to God's command rather than a test of faith, so those who do not feel divinely called to handle snakes are expected to refrain [source: Scott]. (Snake handling is just one element of what is otherwise a standard Pentecostal service [source: Handwerk].)

Many practitioners do handle snakes, fully aware of the potential dangers [source: Handwerk]. The risks are undeniable.

Holiness serpent handling is prohibited in nearly every U.S. state where it occurs, but enforcement is rare [sources: Burnett]. Children in these churches are barred from handling snakes, and adults are not obligated to do so, leading authorities to generally leave practitioners alone unless conflicts arise. For example, in 1995, police investigated the death of 28-year-old Melinda Brown, who died after a snake bite in Pastor Coots' church. Some family members disputed claims that she had refused medical treatment, but no charges were filed. Three years later, her husband also died from a snake bite in another church [source: Miller].

Serpent Handling: When Bad Things Happen

This prairie rattlesnake is being milked for its venom. Even experienced milkers are not immune to bites.

© Joe McDonald/Corbis

This prairie rattlesnake is being milked for its venom. Even experienced milkers are not immune to bites.

© Joe McDonald/CorbisOver the past century of holiness serpent handling, approximately 100 individuals have died from snake bites [source: Duin]. Given the risky handling techniques and the refusal of medical treatment, the relatively low death rate seems almost miraculous [sources: Swaine, Wilking and Effron].

Anti-venom has an almost 100 percent success rate when administered promptly [source: ZME Science]. While many congregants are bitten, most survive without medical intervention, though they often suffer permanent damage like losing fingers or hand functionality [source: Handwerk].

Some in the serpent-handling community believe injuries are divine punishment for sin or mistakes, such as not releasing the snake in time after the "spirit leaves them" [source: Loller]. However, the prevailing belief is that outcomes are entirely in God's hands. Bites or deaths are seen as part of His will, and if someone dies, it was simply their time [source: Handwerk].

Injuries are not limited to amateurs. Even seasoned milkers like Bill Haast, owner of the Miami Serpentarium, faced numerous bites. Haast survived over 172 bites in his 60-plus-year career, including one from a blue krait, whose venom is far deadlier than a cobra's [source: Conservation Institute]. A bite in 2003 cost him his right index finger, forcing him to retire at 92 [sources: Hunter, Schudel].

In 2008, conservationist Rafiq Rajput was fatally bitten by an Indian krait while transferring the snake between cages in Pakistan. The local hospital lacked the necessary anti-venom to save him [source: Hasan]. That same year, a 10-foot (3-meter) Burmese python at a Venezuelan zoo killed and partially consumed an inexperienced handler who had entered the snake's enclosure alone during a night shift [source: Telegraph]. In 2013, expert handler Dieter Zorn died within minutes after being bitten multiple times by an Aspic viper during a demonstration in France designed to help people overcome their fear of snakes [source: Sieczkowski].

Despite the frequency with which people handle deadly snakes, particularly novices, the number of fatalities remains surprisingly low. Jamie Coots, for instance, survived nine bites before his death in 2014 [source: Burnett]. Similarly, George Hensley reportedly endured 400 bites before one proved fatal [source: Scott].

Perhaps it’s a miracle. Or perhaps the snakes themselves play a role.

Snake Handling Risks, Revisited

Some herpetologists argue that holiness serpent handling is manipulated. When a team from The Kentucky Reptile Zoo examined the snake room at Coots' church, they discovered what they believed to be neglected and underfed animals. The cages were filthy and overcrowded, with signs that the snakes were not receiving adequate food or water [source: Burnett].

Snakes that are hungry tend to inject less venom compared to those that are well-fed [source: Hayes]. Additionally, unhealthy snakes are less likely to strike, and the venom they do inject is often weaker [source: Burnett].

In 2013, Tennessee authorities, where owning venomous snakes is prohibited, raided the church of snake-handling preacher Andrew Hamblin and seized 53 snakes, all of which were in poor condition. Many of the snakes died shortly after the raid [source: Smietana]. (Hamblin was not charged for the violation.)

Another reason for the relatively low number of snake strikes in churches could be this: Snakes are far less aggressive than commonly believed.

Snakes do not view humans as prey [source: Welcome Wildlife]. When they attack, it’s typically in self-defense, and even then, snakes prefer to flee rather than bite [source: Snake Getters]. While venomous snakes are more assertive than constrictors, they still prioritize escape [source: Hubbell]. From an evolutionary standpoint, striking at large predators like humans is risky, as they can easily harm the snake before the venom takes effect [source: Snake Getters].

Venom is a valuable resource for snakes, used primarily to subdue prey, so they conserve it and only deploy it when absolutely necessary [source: Kamler]. Pit vipers, such as rattlesnakes and copperheads, deliver "dry bites"—bites without venom—about 25 percent of the time [source: Barish and Arnold].

Perhaps serpent handling is not as perilous as it appears. Alternatively, it might be that fewer injuries occur due to the handlers' strong faith. Or it could simply be a matter of luck. As the experts at Snake Getters put it:

The rattlesnake responsible for Pastor Coots' death was back in church the following week, now handled by the late pastor's son [source: Kuruvilla].

Indian "snake charmers" create the illusion of snakes responding to flute music, but the reality is different. Snakes lack external ears and cannot hear as humans do. The snake's swaying is a response to the flute's movement, which it perceives as a potential threat, keeping its focus on the object to monitor for danger [source: Flintoff].