Mammal Image Gallery Over time, humans have domesticated creatures like these, transforming them into obedient and trusting companions that now coexist peacefully in our homes. Explore more mammal images.

Jan van Gool/The Bridgeman Art Library/Getty Images

Mammal Image Gallery Over time, humans have domesticated creatures like these, transforming them into obedient and trusting companions that now coexist peacefully in our homes. Explore more mammal images.

Jan van Gool/The Bridgeman Art Library/Getty ImagesIn modern times, the domestication of animals is often overlooked. However, from providing meat and dairy to offering loyal companionship, domesticated animals have delivered countless resources, services, and labor, significantly shaping human history.

Initially, humans relied on animals primarily for sustenance. However, it soon became apparent that animals could also serve purposes such as labor, clothing, protection, and transportation. In their natural habitats, animals are wary and self-protective. Yet, humans have managed to alter this behavior. Gradually, certain species grew more docile and responsive to human commands—a phenomenon known as domestication. This process involves an entire species adapting to thrive alongside and interact with humans.

It's crucial to recognize that not everyone views animal domestication positively. Ingrid Newkirk, cofounder of PETA, has publicly criticized human intervention in animal lives, opposing the concept of pets entirely. As an advocate for animal liberation, she campaigns for the freedom of all animals in captivity [source: Lowry].

On the other hand, some view the history of animal domestication more favorably. Author Stephen Budiansky contends that domestication is a natural process benefiting both humans and animals. He supports the idea that animals willingly chose domestication, valuing the security of captivity over the unpredictability of the wild [source: Budiansky]. Additionally, he highlights how domestication has saved certain species from extinction.

Despite differing opinions, the impact of animal domestication on human progress is undeniable. Each domesticated species has contributed uniquely, with its own domestication story, yet all follow a similar biological process. Let’s explore how humans facilitate the transformation of a species from wild to domesticated.

A Whole Different Animal: How Domestication Happens

What do pigs eat? Their adaptable diet made them ideal for domestication.

Andrew Sacks/Stone Collection/Getty Images

What do pigs eat? Their adaptable diet made them ideal for domestication.

Andrew Sacks/Stone Collection/Getty ImagesHow did fierce wolves evolve into tiny Pomeranians? To grasp this, we must first understand genetics and evolution. Offspring inherit genes from their parents, determining their traits. Genetic diversity and mutations allow species to change, or evolve, over time. Through natural selection, animals with advantageous traits survive and reproduce, gradually passing those traits to future generations.

In artificial selection, humans select specific traits in animals to pass on to their offspring. For instance, to breed larger horses for labor, humans pair the biggest males and females, increasing the likelihood of larger offspring. Repeating this process over generations results in a larger horse species. Similarly, humans can breed animals for traits like color, size, temperament, or strength. This is how wolves became domesticated dogs, sheep grew woolier, and horses became rideable.

If this is possible, why don’t we have pet pandas or ride zebras? Not all animals can be domesticated. Author Jared Diamond notes that only 14 out of approximately 148 candidate species have been successfully domesticated [source: Diamond]. He suggests that domestication requires specific criteria:

- The right diet: Animals with specialized or expensive diets are harder to domesticate. Species that thrive on affordable, readily available food are preferred.

- Fast growth rate: Domesticated animals must grow quickly to provide a timely return on investment for farmers and herders.

- Friendly disposition: Aggressive animals resist captivity and human handling, making them unsuitable for domestication.

- Easy breeding: Animals that refuse to breed in captivity cannot be domesticated long-term.

- Respect a social hierarchy: Species that follow a dominant leader in the wild can adapt to human leadership.

- Won't panic: Animals that remain calm when confined or threatened, like cows, are easier to domesticate.

Pandas and zebras are too aggressive, resisting human efforts to domesticate them. However, Diamond's list might have exceptions. For example, wolves, ancestors of the dog, are fierce, and cats are solitary. The domestication stories of dogs and cats are unique and will be explored later.

On the following page, we’ll delve into the extensive history of domestication.

History of Domestication

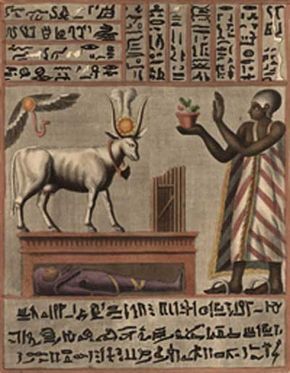

An Egyptian manuscript, discovered alongside a mummy, features hieroglyphics and depictions of ritualistic animals.

Hulton Archive/Stringer/Getty Images

An Egyptian manuscript, discovered alongside a mummy, features hieroglyphics and depictions of ritualistic animals.

Hulton Archive/Stringer/Getty ImagesAnimals have been central to human existence since ancient times. Early cave paintings feature bison and deer, highlighting their importance in our survival, history, and identity. It’s no surprise that humans have sought to integrate animals into their lives for food, companionship, clothing, milk, and countless other purposes.

Archaeological findings, such as fossils, reveal much about the history of animal domestication. This process is closely linked to human domestication, the transition from hunter-gatherer societies to farming. While hunter-gatherers domesticated dogs long before farming emerged, later farmers recognized the value of livestock. Settled farming communities benefited from fresh meat and animal manure for fertilizing crops. Diamond notes that civilizations domesticating animals and plants gained power, spreading their cultures and languages [source: Diamond].

Ancient civilizations domesticated animals for diverse reasons, depending on local species and their potential uses. Animals even held religious significance in cultures like Ancient Egypt and Rome. Here’s where key animals were first domesticated:

- Southwest Asia: Among the first to domesticate dogs, sheep, goats, and pigs.

- Central Asia: Known for raising chickens and using Bactrian camels for transport.

- Arabia: Home to the Arabian camel, or dromedary.

- China: Early domestication of water buffalo, pigs, and dogs.

- Ukraine: Domesticated wild tarpan horses, ancestors of modern horses [source: Rudik].

- Egypt: Utilized donkeys for their endurance with minimal water and vegetation.

- South America: Domesticated llamas and alpacas, saving them from extinction [source: History World].

As animals become domesticated, they undergo significant changes. For instance, their brains may shrink, and sensory abilities may dull [source: Diamond]. These adaptations occur because domesticated animals no longer require the same survival skills as their wild counterparts. Other changes include floppy ears, curly fur, altered sizes, and year-round mating instead of seasonal patterns [source: Encyclopedia Britannica]. These transformations often make domesticated animals look strikingly different from their wild ancestors.

Animal domestication has profoundly impacted humans. For instance, milk consumption has altered our digestive system. Before domestication, most people developed lactose intolerance in adulthood, as they no longer needed breast milk. However, with the rise of livestock farming, increased milk consumption has adapted our digestive systems to tolerate milk throughout our lives.

Next, we’ll explore how the remarkable evolution of dogs led to the creation of humanity’s earliest and most loyal animal companion.

The Beginning of a Beautiful Friendship: Canine Domestication

The modern dog descended from the gray wolf, transforming from a fierce predator into a beloved household pet.

Theo Allofs/Photonica Collection/Getty Images and Daly & Newton/Riser Collection/Getty Images

The modern dog descended from the gray wolf, transforming from a fierce predator into a beloved household pet.

Theo Allofs/Photonica Collection/Getty Images and Daly & Newton/Riser Collection/Getty ImagesThe transformation of a wolf from a wary, wild creature to a loyal, affectionate dog may seem astonishing. However, DNA evidence confirms that the dog likely evolved from the gray wolf.

While the oldest fossils of domesticated dogs date back 14,000 years, DNA analysis indicates that dogs diverged from wolves much earlier, with estimates ranging from 15,000 to over 100,000 years ago [source: Wade]. Historians agree that dogs were the first animals domesticated by humans, making them humanity’s oldest companions.

The exact origins of the bond between dogs and humans remain speculative. One theory posits that humans began raising wolf pups, gradually taming them. Another suggests that the least fearful wolves scavenged near human settlements, gaining a survival advantage. Over time, these tamer wolves evolved into dogs through natural selection [source: NOVA].

Wolves, being pack animals, naturally adapted to humans as their leaders. Tamer wolves stayed close to humans, and through evolution (or selective breeding), they became increasingly docile, eventually leading to the modern dog. This partnership proved advantageous for hunting, combining human strategy with wolf agility and strength, creating a mutually beneficial relationship.

Despite this evolution, the stark differences between dogs and wolves remain puzzling. Russian geneticist Dmitri Belyaev shed light on this by breeding tame foxes. Over generations, the foxes not only became more docile but also developed dog-like traits, offering insights into the wolf-to-dog transformation.

While DNA confirms wolves, not foxes, as the ancestors of dogs, Belyaev’s experiment revealed how behavior and physical traits evolved during domestication [source: NOVA]. As foxes grew tamer, they developed floppy ears, shorter snouts, spotted fur, high-set tails, and even barking tendencies. These traits, absent in wild foxes and wolves, suggest that genes for tameness also influence physical characteristics like floppy ears.

Belyaev’s research also explains the diversity among dog breeds compared to the uniformity of wolves. Tameness introduced variations, which humans selectively bred for specific purposes. Smaller dogs became ideal companions, while larger breeds excelled in hunting. The 19th century saw a rise in dog breeds and the popularity of dog shows, further diversifying canine appearances and roles.

Having explored the domestication of dogs, we’ll now uncover how cats earned their place in our homes and hearts.

In ancient Egypt, dogs were cherished and revered, often reserved for royalty. Purebred dogs wore jeweled collars and had personal attendants. Archaeologists have discovered mummified dogs buried alongside their owners, highlighting their esteemed status [source: Encyclopedia Britannica].

Curiosity Tamed the Cat: Feline Domestication

An ancient Egyptian statue depicting a cat, discovered in the ruins of Bubastis.

Kenneth Garrett/National Geographic Collection/Getty Images

An ancient Egyptian statue depicting a cat, discovered in the ruins of Bubastis.

Kenneth Garrett/National Geographic Collection/Getty ImagesUnlike dogs, cats have not evolved significantly from their wild counterparts, making it challenging for scientists to pinpoint their domestication timeline. While evidence suggests cats did not descend from large modern cats like lions or tigers, archaeologists and geneticists struggle to differentiate ancient small wild cats from modern domesticated cats using bones or DNA. However, researchers theorize that the domestic cat (Felus catus) may have originated from the European wild cat (Felis silvestris) and the African wild cat (Felis lybica), both of which still roam the wild.

Other findings offer compelling insights into early cat domestication. For instance, a 9,500-year-old gravesite contained a human buried with a cat, suggesting a close bond between the two. This intentional burial implies that cats held cultural significance and were valued companions in that society.

While the exact timeline of cat domestication remains unclear, their appeal to humans is easier to understand. Cats’ natural ability to hunt rodents, as humorously depicted in "Tom & Jerry" cartoons, likely made them valuable to humans. In exchange for pest control, cats received food and shelter, gradually overcoming their resistance to domestication.

Cats likely resisted domestication more than wolves or dogs due to their lack of a social hierarchy, which prevents humans from assuming an alpha role. While wolves follow a pack leader, cats are solitary and independent, refusing to take orders. Even though domestic cats are a distinct species, their independence and minimal changes from domestication allow feral cats to thrive on their own, even after being raised in human homes. Perhaps cats remain with humans not out of obedience but for the food and shelter they provide—or, as some might argue, because humans serve them.

While dogs and cats were valuable for hunting and pest control, humans needed other domesticated animals to advance civilization. Next, we’ll explore how animals like cattle contributed to transportation and farming.

Cats held immense significance in Ancient Egypt, achieving god-like status by 1700 B.C. They were immortalized in statues and wall art [source: Bard]. Egyptians frequently mummified cats, treating them with the same care and reverence as humans, as revealed by examinations of these mummies [source: Owen].

Beasts of Burden: Domestication of Cattle and Other Livestock

Sheep and shepherding were widespread during the time of Christ.

Philippe de Champaigne/ The Bridgeman Art Library/Getty Images

Sheep and shepherding were widespread during the time of Christ.

Philippe de Champaigne/ The Bridgeman Art Library/Getty ImagesInitially, livestock provided early farmers with a convenient source of meat and milk. Over time, humans realized these animals could also aid in farming, supply fertilizer, and produce materials for clothing. Below are some key livestock animals that have significantly impacted human history:

- Cattle: The Aurochs, an extinct species, is the ancestor of modern cattle. Domesticated in regions like the Near East and Africa, Aurochs evolved into today’s cattle. Their most notable contribution was plowing fields, which expanded farmland and increased crop yields.

- Oxen: The domestication of oxen around 7000 B.C. was arguably more impactful than the invention of the wheel. Their strength in pulling heavy loads made life considerably easier for early civilizations.

- Sheep: Among the oldest domesticated animals after dogs, sheep were bred to produce wool by reducing their kemp (longer hairs) and enhancing their inner, shorter hair. Herding them was straightforward, as humans assumed the role of leader in their social hierarchy. While domestication began around 9000 B.C., wool weaving likely emerged by 4000 B.C. [source: Tomkins].

- Goats: Goats’ adaptability to harsh, infertile lands made them invaluable. They provided meat, milk, and materials like mohair and cashmere, especially for communities with limited resources [Sherman].

- Pigs: Domesticated from wild boars, pigs thrived on human waste, offering a primitive form of recycling. In return, humans consumed their meat.

Next, we’ll explore other animals that played a crucial role in transporting goods and people over long distances.

Now We're Going Places: Domestication of Transportation Animals

In many parts of the world, camels replaced the wheel as the main mode of transportation for centuries.

Pankaj Shah/ Gulfimages Collection/Getty Images

In many parts of the world, camels replaced the wheel as the main mode of transportation for centuries.

Pankaj Shah/ Gulfimages Collection/Getty ImagesLong before the steam engine, cars, and airplanes, horse-drawn carriages were the primary means of transport. While this may seem rudimentary today, animals like horses enabled significant advancements in civilization through migration and trade for thousands of years. Here are some key animals that revolutionized human transportation:

- Horses: Soil analyses near ancient settlements reveal high concentrations of horse manure, indicating domestication around 5,600 years ago [source: Lovett]. DNA evidence also shows that modern horses descend from various wild herds across multiple regions [source: Briggs]. Initially used for meat and milk, horses later became essential for pulling carts and carrying riders. They enabled humans to travel long distances quickly, making them arguably the most impactful transportation animal. Ancient Romans even used them in chariot races. Interestingly, horses once roamed North America but went extinct, only to be reintroduced by the Spanish millennia later.

- Donkeys: Egyptians domesticated donkeys around the same time as horses. Though donkeys are often undervalued today (evidenced by the term "ass"), ancient Egyptians held them in high regard. Archaeologists have found donkeys buried in special graves, highlighting their importance in Egyptian society [source: Chang].

- Camels: Bactrian and Arabian camels, known for their ability to carry heavy loads and survive with minimal water, were invaluable in desert regions. The Bactrian camel, with its thick coat, can even endure cold climates. Initially used for their hair, meat, and milk, camels later became crucial for transporting goods over long distances, temporarily replacing the wheel in some areas [source: Meri].

While livestock and transportation animals played vital roles in human progress, smaller creatures also made significant contributions. Next, we’ll explore how rodents, insects, and other animals were domesticated to benefit humanity.

The Birds and the Bees: Uses of Other Animals

Workers in China harvesting silkworm cocoons

Keren Su/Stone Collection/Getty Images

Workers in China harvesting silkworm cocoons

Keren Su/Stone Collection/Getty ImagesHumans have domesticated a wide range of animals that serve various purposes. These include:

- Chickens & Roosters: Initially domesticated for cockfighting, chickens were later bred for egg production, which was infrequent until selective breeding improved yields [source: Encyclopedia Britannica].

- Turkeys: Indigenous to America, turkeys were first domesticated by Native Americans in present-day Mexico. Europeans only encountered them in the 16th century, and they remain a staple of American celebrations.

- Bees: Before the 19th century, honey was the primary sweetener, obtained from wild beehives at great risk. Humans later domesticated bees by creating artificial hives. Lorenzo Lorraine Langstroth revolutionized beekeeping in the 19th century with his innovative hive design.

- Silkworms: Silkworms produce cocoons used to make silk. Silk production began in China around 3000 B.C., indicating the domestication of silkworms around that time.

- Rabbits: Ferrets were used to hunt rabbits as early as the first century B.C. Medieval French monks later domesticated rabbits for food.

- Hamsters: Domesticated hamsters trace their origins to a single family captured in Syria in 1930. Initially used in scientific research, they later became popular pets. The entire domesticated hamster population descends from this one family [source: History World].

Some animals on the previous list may not truly qualify as "domesticated." Experts like Jared Diamond define domestication strictly, requiring genetic changes that allow humans to control breeding and diet. While individual animals can be tamed for specific tasks without altering their genetic makeup, this doesn’t constitute domestication. For example, despite Hannibal’s famous use of elephants to cross the Alps, Diamond contends that elephants are merely tamed, as they never evolved into a new species through domestication.