Hannibal Hellmurto, a renowned sword swallower, demonstrates his extraordinary abilities during the Circus of Horrors' Psycho Asylum performance at the Wookey Hole Caves Theatre in Somerset, England, October 2018. Photo credit: Matt Cardy/Getty Images.

Hannibal Hellmurto, a renowned sword swallower, demonstrates his extraordinary abilities during the Circus of Horrors' Psycho Asylum performance at the Wookey Hole Caves Theatre in Somerset, England, October 2018. Photo credit: Matt Cardy/Getty Images.Many perceive sword swallowing as a form of magic. Like most illusions, it appears impossible at first glance. Accepting it as a trick feels more plausible than believing someone can safely maneuver a metal blade deep into their body. During performances, sword swallowers often engage the audience, inviting them on stage to examine the swords or even pull them out, much like a magician building trust.

Various sources suggest sword swallowing involves clever techniques. Harry Houdini, the legendary magician, discussed it in his book "The Miracle Mongers, an Expose," claiming some performers used hidden metal sheaths. Encyclopedia Britannica also describes it as a magic trick, noting that many sword swallowers use guiding tubes, typically 17 to 19 inches long and about an inch wide, to prepare for their acts. [source: Encyclopedia Britannica].

Real sword swallowing involves no illusions or pre-swallowed tubes but requires extensive physical and mental training. For many performers, mastering this skill can take several years.

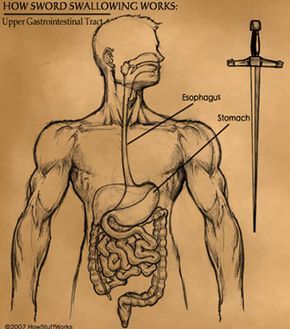

Sword swallowing is the interaction between a human's upper gastrointestinal (GI) tract and a sword. The GI tract, comprising the throat, esophagus, and stomach, is soft and curved when relaxed. In contrast, a sword is rigid and straight, though some performers use wavy or curved blades.

The GI tract acts like a living sheath for the sword. However, unlike a regular scabbard, sword swallowing carries life-threatening risks. Even blunt swords can puncture or damage the GI tract. Swallowing multiple swords increases the danger, as the blades can move like scissors and cause severe internal injuries.

While fitting a sword into a sheath is simple, learning to swallow one demands extensive practice. In the next section, we'll explore the process and how it differs from swallowing food.

Sword Swallowing and the GI Tract

On the left, the naturally curved human GI tract. On the right, a sword of similar length.

Mytour

On the left, the naturally curved human GI tract. On the right, a sword of similar length.

MytourThe human gastrointestinal (GI) tract consists of skeletal muscle, smooth muscle, and a lubricating mucosal layer. Skeletal muscle controls voluntary actions like speaking, typing, and blinking, while smooth muscle manages involuntary functions such as blood vessel dilation and food movement during digestion. Both muscle types work together for essential activities like breathing and eating.

The mouth, pharynx, and upper esophagus are parts of the GI tract made of skeletal muscle, which you can control consciously. When swallowing, your tongue pushes food toward the pharynx, the larynx rises, and the upper esophageal sphincter relaxes, allowing the food bolus to enter the esophagus. The epiglottis blocks the windpipe to prevent food from entering the lungs.

The lower GI tract operates involuntarily. Once the bolus reaches the smooth muscle-lined esophagus, peristalsis begins. Muscle rings contract above the bolus, pushing it toward the stomach. This repeats until the bolus passes through the lower esophageal sphincter into the stomach.

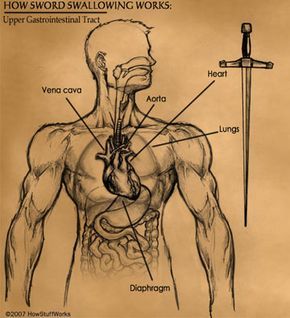

This entire process occurs near other vital organs, including your:

- Trachea, or windpipe

- Heart

- Aorta, the artery that carries blood from your heart toward the rest of your body

- Vena cava, the major veins that return your blood to your heart

- Diaphragm, the sheet-like muscle that moves up and down, allowing you to breathe

Numerous critical structures, including blood vessels and lymph nodes, are located near the throat, esophagus, and stomach. These are the areas a sword navigates as it descends.

In the next section, we'll break down the step-by-step process of swallowing a sword.

Swallowing Food versus Swallowing Swords

A sword being swallowed travels through two sphincters and straightens the GI tract as it moves downward.

Mytour

A sword being swallowed travels through two sphincters and straightens the GI tract as it moves downward.

MytourWhen a performer swallows a sword, it follows the same route as food but involves a very different process. Swallowing food relies on muscle contractions, whereas sword swallowing requires the deliberate relaxation of the upper GI tract. Here's how it works:

- The performer tilts their head back, hyper-extending the neck to align the mouth with the esophagus and straighten the pharynx.

- They consciously move their tongue aside and relax their throat.

- The sword is aligned with the GI tract and guided through the mouth, pharynx, and upper esophageal sphincter into the esophagus. Saliva lubricates the sword, and some performers use additional lubricants like vegetable oil or jelly.

- As the sword descends, it straightens the esophagus's natural curves and may push nearby structures aside.

Occasionally, the sword passes the lower esophageal sphincter and enters the stomach, though this isn't always the case. The distance from the teeth to the stomach's cardia is about 15 inches (40 centimeters). The Sword Swallowers Association International (SSAI) defines a sword swallower as someone who can swallow a 15-inch (40-centimeter) sword, which may not reach the stomach. The SSAI recommends a maximum sword length of 33 inches (83 centimeters), which would place the sword's tip deep into the stomach [source: swordswallow.com].

While these steps may sound simple, mastering sword swallowing is incredibly challenging and should never be attempted without guidance from an experienced professional. In the next section, we'll explore the risks and potential dangers.

The stomach is a curved pouch in the digestive system. For many, the esophagus curves sharply at the stomach's entrance, while for others, the junction is straighter. This anatomical variation significantly affects the length of a sword a performer can safely swallow.

Learning to Swallow Swords

Riley Schillaci, Natasha Veruschka, Kryssy Kocktail, and Lady Aye attended the 6th annual World Sword Swallower's Day at Ripley's Believe It or Not Odditorium in February 2012, New York City. Photo credit: Robin Marchant/Getty Images.

Riley Schillaci, Natasha Veruschka, Kryssy Kocktail, and Lady Aye attended the 6th annual World Sword Swallower's Day at Ripley's Believe It or Not Odditorium in February 2012, New York City. Photo credit: Robin Marchant/Getty Images.Swallowing a sword requires more than just alignment and gravity. Performers must learn to relax muscles usually beyond voluntary control, such as the upper and lower esophageal sphincters and the esophageal muscles responsible for peristalsis.

Additionally, performers must make the act appear effortless, which is no small feat. Anyone who has swallowed a large or poorly chewed bite of food knows how sensitive the esophagus can be. Sword swallowers must guide a cold, rigid blade down their throat and esophagus without displaying any signs of discomfort.

The human body has a defense mechanism designed to block anything other than chewed food from entering the throat — the gag reflex. Accidentally touching the back of your throat with a toothbrush, for example, triggers this reflex. Some people have a highly sensitive gag reflex, activated by even slight contact with the mouth's rear, while others experience it minimally.

A skilled sword swallower must learn to suppress their gag reflex, which is no simple task. Reflexes are involuntary, occurring without conscious effort. They enable actions like pulling your hand away from a hot stove or controlling involuntary bodily functions like urination. These reflexes are essential for survival and operate independently of conscious thought.

Reflexes involve multiple physiological components that create a reflex arc. Here's how it works:

- A receptor, or nerve ending, identifies a threat or event needing immediate attention.

- A neuron transmits the receptor's signal to the central nervous system (CNS).

- The CNS's integration center decides the body's response.

- A motor neuron delivers the CNS's instructions to the relevant body part.

- An effector carries out the necessary physical change.

For the gag reflex, nerve endings in the throat detect an intruding object, sending impulses via a neuron to the brain stem's integration center. The brain stem then uses a motor neuron to direct the muscles in the throat — the effectors — to contract, causing a retch to expel the object. This entire process is involuntary and occurs in an instant.

Mastering the ability to override an involuntary reflex requires extensive practice. For sword swallowers, this often means repeatedly triggering the gag reflex, which can lead to vomiting and significant discomfort. Over time, this process diminishes or eliminates a protective mechanism, highlighting one of the many dangers of sword swallowing. We'll explore these risks further in the next section.

Some sword swallowers incorporate other slender objects into their acts, such as oil dipsticks, medical forceps, drumsticks, and pool cues. These performers genuinely insert these items into their throats. Swallowing a long balloon, however, is an illusion, and revealing how it's done would expose the trick's secret.

The Dangers of Sword Swallowing

When a sword is swallowed, it passes near several critical organs, including the heart, lungs, and aorta.

Mytour.com

When a sword is swallowed, it passes near several critical organs, including the heart, lungs, and aorta.

Mytour.comSword swallowing forces the body to override its natural defenses, making it inherently risky. The practice is also poorly studied in medicine, likely due to the small number of practitioners. The most comprehensive medical research on the subject was published in the British Medical Journal, based on a voluntary survey of 110 English-speaking sword swallowers. Of the 48 respondents, 46 allowed their data to be used, and 33 provided detailed medical histories. The most common side effects reported, in order of frequency, included:

- Throat pain[, or sword throat

- Persistent lower chest pain, likely from injury to the esophagus or the diaphragm

- Internal bleeding

- Esophageal perforations, three of which required surgery

- Pleurisy, an inflammation of the lungs

- Pericarditis, an inflammation of the sac that covers and protects the heart

Some respondents reported severe injuries following particularly painful performances. It's logical to assume that swelling and tissue damage from minor injuries could escalate into more serious conditions. Sinus infections are also a risk, as the practice involves introducing non-sterile objects near sinus-connected tissues.

The survey only included living sword swallowers, so it didn't cover fatalities. However, medical literature has documented deaths linked to sword swallowing. One BMJ article recounts a performer who died after attempting to swallow an umbrella. Historical medical texts also mention cases of people allegedly living for years with knives in their stomachs.

Not all medical discussions about sword swallowing focus on injuries or deaths. In the 1800s, during the early days of endoscopy, rigid instruments were common. Researchers occasionally collaborated with sword swallowers, whose throats could accommodate these inflexible tools.

Despite the risks, many sword swallowers are self-taught, while others learn from experienced performers. Some even attend organized classes, such as those offered at the Coney Island Sideshow School.