For a time in the early 1980s, the most despised figure in Memphis, Tennessee, was a comedian hailing from Long Island.

Andy Kaufman had spent years as a stand-up comedian, honing a distinct form of confrontational performance that would rile audiences. He provoked them by reciting passages from The Great Gatsby, miming the theme song from Mighty Mouse, and even taking naps onstage. Despite his mainstream success on the sitcom Taxi as Latka Gravas, Kaufman still sought to upset the status quo. In wrestling terms, he was a classic ‘heel’—a villain who thrives on drawing the crowd's ire.

In 1981, Kaufman embraced the role of a heel where it would have the greatest impact: the wrestling ring. Lacking athletic skill, experience, and with minimal financial rewards, he entered the world of professional wrestling, becoming one of the most captivating figures Memphis had ever known.

He did so by challenging women to wrestle him.

Kaufman grew up on Long Island and honed his craft with unpaid gigs in comedy clubs before earning recognition for his guest appearances on Saturday Night Live. This led to a role on Taxi, followed by a successful tour where Kaufman would entertain by impersonating Elvis Presley or escorting 2000 fans out for milk and cookies after performing at Carnegie Hall.

As a child, Kaufman was a fan of professional wrestling and looked up to “Nature Boy” Buddy Rogers. He once witnessed Rogers face Bruno Sammartino at Madison Square Garden, with Rogers—playing the villain—drawing boos from the audience. This moment likely resurfaced in Kaufman’s mind when, in 1977, he started challenging women in the crowd to wrestle him. If they could pin him, he promised them $1000.

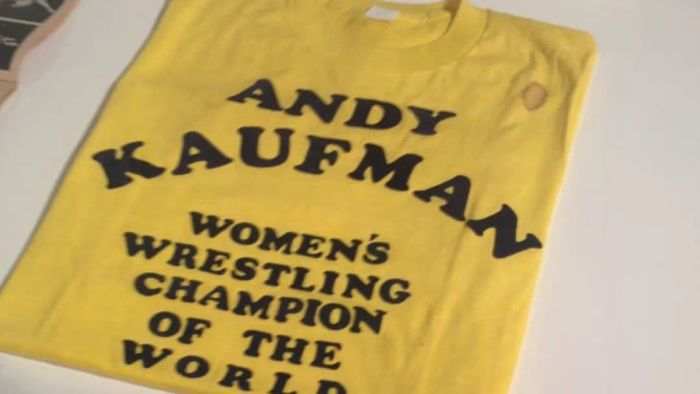

Andy Kaufman’s wrestling memorabilia on display at New York City's Maccarone gallery. | Jack Szwergold via Flickr // CC BY-NC 2.0

Andy Kaufman’s wrestling memorabilia on display at New York City's Maccarone gallery. | Jack Szwergold via Flickr // CC BY-NC 2.0Estimates vary on how many times Kaufman wrestled women, with numbers ranging from 60 to over 400. While some of these matches may have been staged, Kaufman appeared genuinely engaged in physical contests with many of the volunteers. The reactions from his audience—ranging from amusement to confusion—were exactly what Kaufman wanted, but he sought a bigger stage. On October 20, 1979, during an appearance on Saturday Night Live, Kaufman made his challenge while wearing his signature wrestling attire: black trunks over white long johns. He explained that he wasn’t interested in wrestling men because they might defeat him, but he was ready to face any woman who dared to take him on.

A pregnant woman stepped forward to volunteer, but Kaufman declined to wrestle her. Instead, he faced Mimi Lambert, a dancer and heiress to the Lacoste sportswear fortune. After several minutes of wrestling, Kaufman was victorious. In an unexpected turn, he then challenged Olympic swimmer Diana Nyad to a match, offering $10,000 to her if she won, before clucking like a chicken.

Andy Kaufman returned to Saturday Night Live multiple times that year to continue his challenges, even going so far as to “threaten” host (and future Golden Girl) Bea Arthur.

Kaufman finally found an opponent in Diana Peckham, the daughter of Olympic wrestling coach James Peckham, and they squared off on the December 22, 1979 episode of SNL. Despite having his childhood hero Buddy Rogers in his corner, Kaufman was unable to defeat Peckham, and the match ended in a draw.

Kaufman then began reaching out to wrestling promoters, including the renowned New York promoter Vince McMahon Sr., declaring himself the World Inter-Gender Wrestling Champion and stating that he would defend his title against anyone. He remained undefeated, with the exception of one loss to six women simultaneously at a Chippendales club in Los Angeles.

Once again, Kaufman was ahead of his time. This was in 1981, years before Vince McMahon Jr. would transform wrestling with grand spectacles like WrestleMania and bring in celebrities like Mr. T, Cyndi Lauper, and Liberace. Under different circumstances, Kaufman might have found a place in this showbiz era. However, McMahon Sr., a staunch wrestling traditionalist, wanted no part of it.

Disappointed, Kaufman sought advice from his friend and wrestling journalist Bill Apter, who suggested he reach out to Jerry Lawler, Memphis’s most beloved wrestler. Alongside his partner Jerry Jarrett, Lawler ran the Continental Wrestling Association (CWA). Intrigued by the idea, Lawler invited Kaufman to Memphis, knowing his celebrity status and exaggerated male chauvinist persona would surely capture attention.

For months, Kaufman sent in video messages taunting the Memphis locals. Then, on October 12, 1981, he stepped into the ring at the Mid-South Coliseum, wrestling three women back-to-back. On November 23, he upped the ante by facing four women, with the fourth competitor, Foxy Brown, managing to secure a draw. Both Kaufman and Lawler saw potential in a rematch — this time with Lawler in Brown’s corner — knowing it would captivate the crowd.

Their instincts were right. On November 30, 1981, Kaufman defeated Brown in a decisive victory. But the spectacle didn't end there. Outraged by Kaufman’s unsportsmanlike behavior, Lawler stormed the ring to confront him. In that moment, Kaufman and Lawler recognized the chemistry they had. The narrative of the hometown hero standing up to the arrogant Hollywood villain resonated, and Kaufman saw a chance to fully embody his wrestling idol Buddy Rogers by stepping into the ring with a man.

For months, Memphis wrestling fans tuned in to watch Kaufman’s relentless mockery. “I’m from Hollywood!” he declared, repeatedly insulting them. He mocked their hygiene, offered condescending lessons on using soap, and perpetuated offensive Southern stereotypes. He boasted that women’s rightful place was in the kitchen, “scrubbing potatoes.” If Kaufman had dared to walk Memphis’s streets without protection, the backlash might have been severe.

At last, Kaufman and Lawler faced off on April 5, 1982. Approximately 11,200 fans packed the Mid-South Coliseum, eager to watch Lawler put Kaufman in his place. While some in the crowd likely knew the two were playing roles, they were still invested in the drama. (In fact, they had rehearsed the moves two nights before at referee Jerry Calhoun’s house.) The match lasted less than seven minutes, with Kaufman mainly evading Lawler and offering little resistance, aside from a basic headlock. Eventually, Lawler caught him, dropping Kaufman to the mat with a series of piledrivers.

But the spectacle didn’t end there. Kaufman stayed in the ring for another 15 minutes, twitching his legs and demanding an ambulance. Lawler joked that it would cost $250 to summon one, to which Kaufman agreed to pay. Kaufman was carted off on a stretcher, spending the next few days giving interviews from his hospital bed, claiming that he had sustained serious injuries in what he described as a real contest. Though Kaufman did admit the piledrivers had caused him pain, it seemed unlikely that his injuries were severe enough to warrant a three-day hospital stay.

However, Kaufman’s dramatic performance was apparently convincing enough to fool The New York Times, which covered his recovery as if it were genuine:

“[Lawler] insisted the bout be a real thing. It was, too … As a result, said George Shapiro, the comedian’s manager, Mr. Kaufman suffered cuts on the top of his head, strained neck muscles, and a compressed space between the fourth and fifth vertebra. Hospital officials listed him in good condition yesterday.”

In a 2012 article for CNN, journalist Wayne Drash recalled being a kid in Memphis and going to school the day after the match. A classmate, convinced Kaufman was truly injured, suggested the class pray for him—but was met with boos.

Although their rivalry seemed to have reached its peak, Kaufman and Lawler were determined to take their feud to an even bigger platform. On July 28, 1982, both appeared on Late Night with David Letterman, which had only been airing since February that year. During the segment, Kaufman—wearing a neck brace—continued his fiery rhetoric against Lawler, provoking the wrestler to slap him across the face while a perplexed Letterman looked on.

Much like Kaufman’s earlier “injuries,” the mainstream media took some time to recognize that this stunt was orchestrated. Kaufman further solidified the ruse by filing a $200 million lawsuit against NBC, claiming he would soon take over the network and transform it into an all-wrestling channel. His bouts with Lawler continued to pack arenas in Memphis, Indiana, and Florida, eventually prompting Vince McMahon Jr. to tell Lawler that he was envious of the Memphis wrestling scene for having Kaufman as its “master heel.”

Kaufman never fully abandoned his love for wrestling. In 1983, he starred in My Breakfast with Blassie, a parody of the 1981 film My Dinner with Andre, alongside the legendary wrestler “Classy” Freddie Blassie. Kaufman also played a wrestling referee in the Broadway musical Teaneck Tanzi, which told the story of a woman (Deborah Harry of Blondie) who wrestles the men in her life. The show, however, opened and closed in a single night.

Kaufman tragically lost his battle with lung cancer on May 16, 1984, at the age of 35. Had he lived, he likely would have continued his career in wrestling. Reflecting on their time together, Lawler once said that Kaufman had expressed a wish: if he could give up acting, he would have pursued wrestling full-time.

Additional Sources:Lost in the Funhouse: The Life and Mind of Andy Kaufman.