When NBC's medical drama St. Elsewhere concluded after six seasons on May 25, 1988, its unique finale left many viewers disappointed. The show, which had won 13 Emmy Awards, ended with an unconventional scene: Tommy Westphall (Chad Allen), the son of Dr. Donald Westphall, stared into a snow globe containing a tiny replica of St. Eligius, the hospital from the series. Behind him stood his father, dressed in work clothes.

The conclusion suggested that Tommy, a character on the autism spectrum, had created the entire series in his mind. This narrative device, a fictional story within a story, had previously caused backlash on Dallas five years earlier, where Bobby Ewing was revived after his death was revealed to be a dream.

Bruce Paltrow, one of the show's executive producers, anticipated mixed reactions, telling the Chicago Tribune in 1988, 'I expect a very mixed reaction. Some will find it extraordinary and existential, quintessential St. Elsewhere. Others may see it as puzzling, strange, or even unsatisfying.'

For some, the ending presented an intriguing puzzle. If the world of St. Elsewhere existed solely in Tommy Westphall's imagination, then other television characters who had appeared on the show must also be part of his mind. The characters from Cheers, which spawned Frasier and featured characters from Wings, and the detective John Munch from Homicide—who appeared in shows like The X-Files and The Wire—became part of what is now known as The Tommy Westphall Universe theory.

As of now, 441 television shows can be connected to St. Elsewhere, spanning from I Love Lucy to The Flash, each with varying degrees of linkage. If the theory is accurate, a significant portion of television could be the product of one child's vivid imagination.

Tom Fontana never intended to erase the fiction of an entire medium. As a producer on St. Elsewhere, he was firmly opposed to the idea of a reunion special and believed the series' finale should stand as the definitive end.

Fontana’s original vision for the finale was a literal apocalypse, where the St. Eligius staff would survive in 2013 while a deadly toxic gas cloud, the byproduct of a corporate war between foreign powers, swept over. When NBC declined to fund the ambitious plan, the snow globe idea was conceived. (In a 2012 interview with IndieWire, neither Fontana nor co-writers Channing Gibson or John Tinker could recall who came up with the concept.)

However, Fontana did remember that the viewer mail received after the finale was split: half of it was positive, while the other half included comments about wanting to 'burn [the studio lot] to the ground.'

Following St. Elsewhere, Fontana went on to create the iconic crime drama Homicide: Life on the Street and the groundbreaking HBO prison series Oz. These successes would likely have overshadowed the strange ending of St. Elsewhere in Fontana's legacy, had it not been for the interest of playwright Keith Gow.

Gow, a Melbourne-based resident, spent his time in pubs and online pondering the significance of Tommy's snow globe scene for the entire universe of shows tied to St. Elsewhere. "The conversation began on alt.tv.homicide, a newsgroup dedicated to Homicide: Life on the Street," Gow tells Mytour. "Fontana often included references to his previous work, even bringing St. Elsewhere characters into Homicide."

Together with U.S. fan Ash Crowe, Gow began creating a chart that connected St. Elsewhere to other TV shows. Over time, it evolved into something resembling the Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon game.

Here’s an example of how St. Elsewhere ties into Doctor Who [PDF], hypothetically turning the TARDIS into a product of Tommy’s imagination:

Dr. Donald Westphall and two other doctors visited Sam Malone’s bar in Cheers; Cheers introduced Frasier Crane, a character from Frasier; John Hemingway from The John Larroquette Show once called into Frasier’s talk show; The John Larroquette Show mentioned Yoyodyne, a manufacturing client of law firm Wolfram and Hart; Wolfram and Hart represented another client, Weyland-Yutani, which made a weapons display screen for Firefly; A Weyland-Yutani ship appears in the BBC series Red Dwarf, which also depicted The Doctor’s TARDIS.

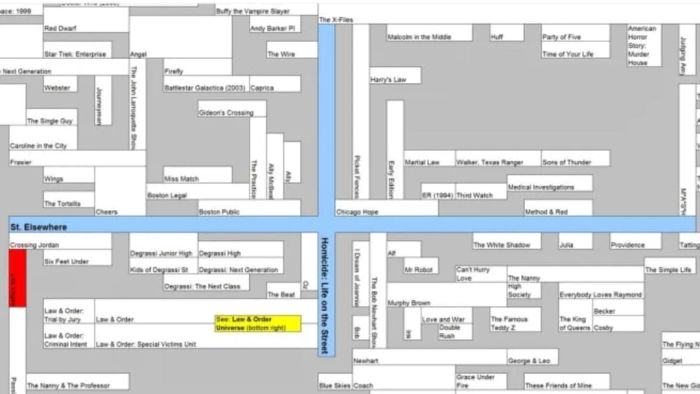

A glimpse of the Westphall grid. | Courtesy of Keith Gow

A glimpse of the Westphall grid. | Courtesy of Keith GowThese connections span decades of television, with I Love Lucy being the earliest example. Often, characters crossing over on the same network create links, with shared brands or locations acting as bridges for others. The fictional Morley cigarettes are especially widespread, as is Hudson University, a fictional institution referenced on The Cosby Show, Law & Order, and Murder, She Wrote.

"Personally, I prefer character connections," says Gow. "They really cement the links. Most of the connections in the grid are character-based, although something like Morley cigarettes (a fictional brand) creates multiple connections, adding to the overall network in subtle ways. The fictional brand or company angle is also a result of Fontana’s influence. The corporation that acquired St. Elsewhere in its final season owned the prison hospital featured in Fontana's series Oz."

As the chart expanded, aided by reader input, The Tommy Westphall Universe grew to include shows as varied as ALF, The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air, Knight Rider, Melrose Place, Seinfeld, and many others. Much of this expansion was fueled by the character of Munch appearing in over 10 series, each making references to other characters and brands.

While Gow and Crowe were compiling their chart, comic writer Dwayne McDuffie (Static Shock) penned a blog post for Slush.com in 2002 that noted a similar trend. "St. Elsewhere also shared characters with The White Shadow and It’s Garry Shandling’s Show," McDuffie wrote. "Garry Shandling crossed over with The Andy Griffith Show (yes, really!). Therefore, Gomer Pyle, U.S.M.C., Mayberry R.F.D., and Make Room for Daddy/The Danny Thomas Show are now gone. Make Room For Daddy connects back to I Love Lucy.”

McDuffie argued that everything on television, except for the brief moments viewers shared with Tommy Westphall in May 1988, supports his Grand Unification Theory: it’s all just a daydream.

As a co-creator of the scene that sparked the entire concept, Fontana revealed he was “stunned” by the aftermath, acknowledging that the theory “essentially means Tommy Westphall is the mind of God.”

Fontana’s remark was likely made in jest (or at least we hope so), but not everyone was as keen on the idea. Critics of the theory argue that it misinterprets the author's intent. While the doctors from St. Elsewhere visited the Cheers bar, the creators of Cheers never agreed to have their show considered fictional. Additionally, there’s no reason to rule out the possibility that the final scene in St. Elsewhere was itself a dream, rendering the snow globe scenario irrelevant. And what about the real people who appeared in the linked shows, such as Alex Trebek on Cheers? If Cheers is fictional, does that make Trebek fictional as well?

However, the theory doesn't rely solely on Tommy imagining everything: The connections remain, whether viewed as a dream within fiction or as part of an interconnected TV universe. "The theory isn’t completely about Tommy Westphall, but he makes for a great central point," Gow says.

Gow and Crowe, who continue to update the grid periodically, maintain that episodes featuring real people playing themselves—such as Trebek’s cameo on Cheers—are excluded, as well as cartoons and feature films. This would undoubtedly result in massive spreadsheets: Weyland-Yutani is the corporation behind the events in the Alien franchise.