A hybrid is the product of two distinct species coming together. Some emerge naturally, while others are engineered in a laboratory setting. Yet, there is a select group of hybrids that represent first-time occurrences in this fascinating world.

When scientists create hybrids, it's not just about novelty. These creatures have the potential to save endangered species and even help cure human diseases. Nature is full of surprising combinations. When exotic pets are introduced to the wild or rare species struggle to find mates, the instinct to reproduce often drives them to cross species lines.

10. The Wholpin

While conducting research around the Hawaiian island of Kauai, scientists stumbled upon an intriguing sight. A dolphin-like creature appeared repeatedly. Photographs suggested it was a hybrid, displaying characteristics from multiple species.

In 2018, a year after the creature was first observed, researchers tranquilized it. The dart was non-lethal, and a skin sample was collected. DNA analysis revealed that the creature’s father was a rough-toothed dolphin, and its mother was a melon-headed whale.

This ‘wholphin’ became the first of its kind to be officially recorded and was even given the scientific name: Steno bredanensis. While this rare hybrid might turn out to be sterile, its birth itself wasn't exactly unprecedented.

The melon-headed whale is classified as a type of dolphin. In theory, these so-called misnomers could easily produce numerous wholpins with other dolphin species. While this hasn't occurred yet, the scarcity of melon-headed whales in Hawaii may contribute to the phenomenon.

9. Cotton Candy Grapes

For those who love healthy snacks and the nostalgic taste of carnivals, there's now a fascinating fruit—grapes that taste just like cotton candy. And for those concerned about genetic modification or artificial flavoring, rest assured. These grapes are a product of natural breeding.

Horticulturists from California selected two varieties to crossbreed. The first was a type of Vitis vinifera, a common variety found in grocery stores. The other was a Concord-like grape, commonly used in Welch’s jellies, juices, and jams.

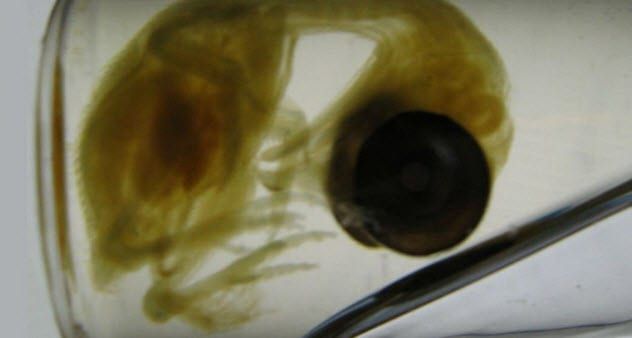

Both varieties are seedless and cannot reproduce naturally, pushing scientists to embark on a challenging journey of extracting grape embryos, cultivating them in test tubes, and then transplanting them into vineyards. After about 100,000 test tubes, the Cotton Candy grape hybrid finally came into existence.

With 12 percent more sugar than typical grapes, this fruit became a sensation when it hit the market in 2011. The increased sugar content also helps prevent a common problem with produce—grapes that lose their flavor by the time they reach consumers.

8. Hybrid Hope For Rhinos

In 2018, the last male northern white rhino passed away. The remaining females, his daughter and granddaughter, are infertile. However, thanks to frozen sperm and the southern white rhino—the only species not currently endangered—there’s hope for reviving their nearly extinct northern cousins.

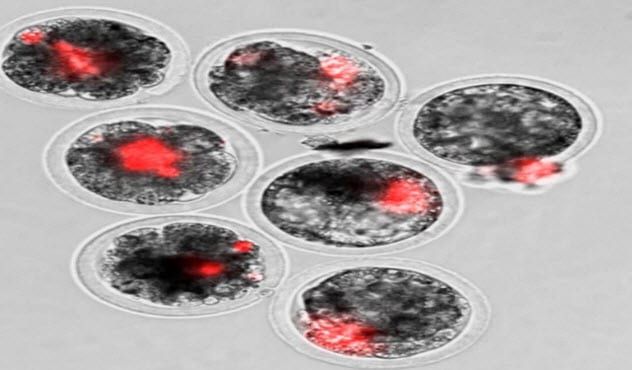

Although the northern and southern white rhinos are different species, scientists successfully created hybrid embryos using sperm from four northern rhinos and eggs from two southern females. This marks the first step in the challenging effort to bring the species back. Even if surrogates successfully carry the hybrids to term, they will represent only a small fraction of what’s needed to rebuild a sustainable herd.

Plans for the future involve collecting eggs from the last two northern white rhino females. These females can still produce eggs, but they are unable to carry embryos to term. This process would allow scientists to create fully-grown northern white rhinos. Another bold plan is to generate sperm and egg cells from their skin cells, a method already proven successful in mice.

7. Florida’s Hybrid Pythons

The Burmese python is a top pick for exotic snake lovers in the United States. However, some owners found them too much to handle and released them into the wild. These giant snakes, reaching lengths of 7 meters (23 feet) and weighing as much as 91 kilograms (200 pounds), quickly adapted to Florida’s environment. First spotted in the 1980s, they eventually spread, and today, thousands are now slithering through the state.

In 2018, scientists analyzed tail samples from 426 pythons in southern Florida and found that 13 of them were hybrids. While predominantly Burmese, these 13 snakes also carried the genetic material of another invasive species—Indian pythons—released by owners who no longer wanted them.

Originally from India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and Nepal, these snakes were smaller but faster. Interestingly, genetic evidence shows that the two species did not recently give rise to the first hybrid offspring. They had interbred long before the Florida pythons reached significant numbers.

The newly identified hybrids may be more robust and adaptable than their parent species, which poses a threat. Local wildlife, particularly small mammals, are frequently preyed upon by these massive reptiles.

6. The Galveston Dogs

Red wolves once roamed the southeastern United States. Due to human activity, their numbers dwindled, and by 1980, the last remaining wolves were placed in breeding programs. Only 17 pure individuals remained. From this small group, efforts to breed them successfully led to the establishment of a pack in North Carolina, now about 40 strong, with another 200 individuals in captivity.

In 2019, a biologist was taking photos of wild dogs in Galveston, Texas, when he stumbled upon a group that seemed distinct from the local coyotes. Convinced that they were different, he theorized that these could be red wolf hybrids and sent both photos and physical samples for analysis. These samples came from animals that had been struck by vehicles.

To his surprise, the biologist’s theory was right, and this discovery might play a crucial role in saving the endangered predator. The Texas pack contained DNA unique to the red wolf, along with “ghost alleles,” which didn’t match any known canine genes, even those of the red wolf.

These genetic markers were likely lost during previous breeding programs but were preserved in the Galveston dogs. Scientists now aim to use these animals to restore lost genetic traits to the red wolf and to improve the population’s health and numbers.

5. Chicken With Dinosaur Legs

Recent fossil discoveries confirmed that certain dinosaurs not only survived but evolved into the birds we see today. In 2016, scientists in Chile set out to observe the transformation of dinosaur leg bones through time. Similar to modern birds, dinosaurs had two bones in their lower limbs: the fibula and tibia. The fibula was a long tube that extended down to the ankle, while the tibia was roughly the same length and positioned alongside it.

As evolution progressed, the next generation of avian dinosaurs, known as pygostylians, emerged. By this time, the fibula had shortened and developed a tapered, splinter-like end. Modern bird embryos still show signs of forming long dinosaur-like fibulae, but they eventually shorten and develop the pygostylian ends.

To observe this evolutionary change firsthand, scientists suppressed the IHH gene in chicken embryos. This manipulation resulted in leg bones of equal length, reaching down to the ankle, much like those seen in dinosaurs.

While the dino-chickens did not survive to hatch, their development revealed that the IHH gene played a crucial role in preventing the bones from reverting to their dinosaur origins. This experiment marked the first time researchers observed the dinosaur-to-bird transition in living organisms, something that had previously only been evident in fossils.

4. Human-Sheep Hybrids

While the idea of creating a human-sheep hybrid may sound unusual, the ultimate goal is to save lives. By advancing this project, researchers hope to address the worldwide shortage of donor organs and possibly even find a cure for type 1 diabetes.

In 2018, Stanford University successfully developed the first embryos that combined human and sheep cells. These embryos were allowed to grow for a short period inside a surrogate animal before she was euthanized. Unfortunately, laws currently prevent hybrids from living beyond 21 days.

Though the project ended at that point, it marked the beginning of a potential breakthrough in creating unlimited human organs, particularly the pancreas, within farm animals. Previous experiments had successfully cured a diabetic mouse using a pancreas grown inside a rat.

Researchers plan to breed genetically modified sheep lacking specific organs and hope that the sheep’s human DNA will trigger the creation of a pancreas. However, in order to reach that stage, the experiment must run for at least 70 days, requiring special permission from regulatory authorities.

3. The Hybrid That Became A Species

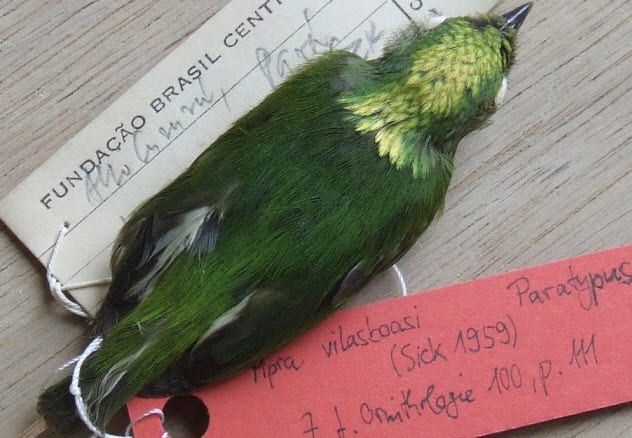

The Amazon is home to some truly strange creatures, but one bird left even experts baffled. In 1957, a new variety of manakin was discovered and named the golden-crowned manakin. This small bird appeared to be a distinct species with its own population and territory, and nothing seemed out of place. But after its initial discovery, the bird disappeared for 45 years until 2002.

In 2018, genetic testing revealed that these rare birds were actually hybrids. They carried 20 percent of the snow-capped manakin’s DNA and 80 percent of the opal-crowned manakin’s. While hybrid animals are not unusual, this was the first time a hybrid bird species had ever been identified on Earth.

Even more astonishing, the parent species of these birds had created the golden-crowned manakin about 180,000 years ago. Against all odds, and defying the usual fate of most hybrids, this bird became a fully-fledged species in its own right.

In addition to showing that not all hybrids are recent, the golden-crowned manakin also displayed physical differences from its 'parents.' All three species shared green bodies, but their head colors varied. The snow-capped manakin had a white head, while the opal-crowned manakin's head sparkled with iridescent hues. The golden-crowned manakin, however, developed a bright yellow cap.

2. Extinct Tortoise Could Be Alive

Around 150 years ago, a giant tortoise species was declared extinct. The last known sighting occurred on Floreana Island, part of the Galapagos Islands in the Pacific Ocean. Chelonoidis elephantopus was recognized by its distinctive saddle-shaped shell, unlike the domed shells of other tortoise species found on the islands.

These massive tortoises could grow up to 1.8 meters (6 feet) in length and weigh as much as 408 kilograms (900 pounds). Recently, scientists have observed a shift in another giant tortoise species, raising hopes that this extinct species might not be gone after all.

Chelonoidis becki is found on Isabela Island, approximately 322 kilometers (200 miles) from Floreana. Some of these tortoises feature saddle-shaped shells, though domed shells were expected. Researchers collected genetic samples from 1,669 tortoises, and astonishingly, 84 of them had genetic markers indicating one parent was the extinct C. elephantopus. Even more promising, 30 of these hybrids were younger than 15 years old.

The genetic diversity also revealed that at least 38 different C. elephantopus tortoises may have left descendants on Isabela. Since these tortoises can live up to 100 years, it's possible that some of the original C. elephantopus still exist. If confirmed, this would mark the first rediscovery of a species through its hybrid descendants.

1. Burket’s Warbler

In Pennsylvania, blue and golden-winged warblers frequently interbreed. Their hybrid offspring are classified as either Brewster’s or Lawrence’s warbler, based on their distinctive colors.

In 2018, a passionate bird-watcher captured a photograph of what he believed was a Brewster’s warbler. However, after reviewing the images, Lowell Burket, with his keen eye, spotted unusual markings on the bird that didn’t fit the typical pattern.

The bird displayed two chest patches that did not belong to the same genus. Suspecting that the bird was a hybrid of a chestnut-sided warbler and a blue-gold warbler, Burket waited for the bird to sing. Warbler species are known for their unique songs, and when this particular bird sang, its song was identical to that of a chestnut-sided warbler.

The birdwatcher shared his findings—photos, videos, and his hypothesis—with ornithology experts. Convinced by the compelling evidence, they assisted Burket in capturing the bird. Genetic testing confirmed that the warbler’s mother was a Brewster’s hybrid and its father a chestnut-sided warbler. The rare three-species hybrid was named Burket’s warbler in recognition of its discoverer.