France's past stretches back over thousands of years, filled with ancient remnants. The country holds villages with hidden messages, peculiar cemeteries nestled within schools, and even towns that are actually forgotten cities.

History reveals its darker side too. From bound bodies to bloody massacres, the violent legacy of ancient France is imprinted on its archaeological sites.

10. The Oldest Muslim Graves

In 2016, excavations in Nimes revealed about 20 graves. Discovered amidst Roman ruins, the burial site was too disordered to be considered a cemetery. Further analysis uncovered three unusual individuals. Several signs indicated that the medieval burials were of Muslim origin. The bodies were oriented towards Mecca, and the tombs' sockets matched those found in other Muslim graves.

Historically, the Arab-Islamic conquest left its mark across the Mediterranean and the Iberian Peninsula. In France, Muslim graves had previously been discovered in Marseille and Montpellier.

However, those graves were from the 12th and 13th centuries, while the ones in Nimes date back to between the 7th and 9th centuries, making them the oldest Muslim graves discovered in France.

Despite the surprise surrounding these burials, their existence wasn't entirely unexpected. Historical records confirm that Muslims were present in France during this period. DNA analysis revealed that the three men were likely Berbers, a North African group that embraced the Arab religion during the early Middle Ages.

9. The Kindergarten Bones

In 2006, a group of toddlers experienced a chilling moment during playtime. One adult noticed the children pulling human bones from the ground and quickly informed the police.

It was discovered that the kindergarten in Saint-Laurent-Medoc was built on an ancient burial mound. Archaeologists unearthed 30 skeletons, believed to be from a Bronze Age group known as the Bell-Beaker culture.

A recent study of the Le Tumulus des Sables burial mound uncovered an astonishing mystery. For reasons that remain unclear, people continued to return to the site for 2,000 years (from 3600 BC to 1250 BC) to bury their dead. Archaeologists are puzzled as to why this simple, unembellished site was in use for such an extended period.

The study also revealed that only six of the individuals were from the Bell-Beaker culture. Surprisingly, they seemed to have been locals, as opposed to the typically nomadic Bell-Beaker people, who are known to have moved across Europe.

Another strange finding was their diet. Analysis of their teeth revealed that they avoided fish and seafood, despite the region being surrounded by estuaries, rivers, and the Atlantic Ocean.

8. Shackled Skeletons

In 2014, researchers revisited a cemetery discovered a year prior. This necropolis, built by the Romans, was located near the town of Saintes.

The team uncovered hundreds of graves, among which were several individuals bound in chains. These weren't temporary restraints; three men had iron shackles permanently attached to their ankles.

Another adult, whose gender remains unidentified, wore a metal 'bondage collar.' This restraint was a large ring fastened around the neck. Tragically, a child's body was found with a similar fate—the youngster had been buried with a restraint around the wrist.

No grave goods were found alongside the shackled skeletons, indicating their likely low social status during life. While little is known about them, it's believed they were enslaved by the Romans in the second century AD.

7. The Arago Tooth

In 2015, Valentin Loescher took part in an archaeological excavation. The 20-year-old was assigned to Arago cave in southwestern France, a site previously known for the discovery of the Tautavel man, a Neanderthal ancestor who lived around 450,000 years ago.

While brushing away dirt, Loescher discovered a large human tooth. At first glance, a single tooth may seem insignificant, but it holds immense value. The wear on a fossilized tooth can reveal details about a person's diet and health. Teeth also contain DNA, providing genetic information such as gender and ethnicity.

Although future research could help profile the person who lost the tooth, initial dating tests showed it was about 560,000 years old. This alone made it a significant find. Not only did it predate Tautavel man by more than 100,000 years, but it could also offer insights into a period that left few human traces in Europe.

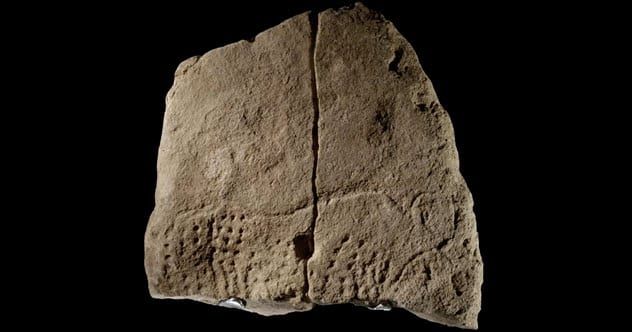

6. The Aurochs Slab

France is home to many ancient rock shelters. In 2012, archaeologists conducted an excavation in one of these shelters located in the southwestern part of the country. While exploring the cave, they uncovered a block of limestone on the floor. Upon turning it over, they found what could be one of Europe's oldest artworks.

Around 38,000 years ago, an artist depicted the now-extinct cattle known as aurochs. The artwork also featured dozens of dots. The decision to excavate at the cave, named Abri Blanchard, was influenced by the fact that the region—and the shelter itself—had previously yielded carved slabs and artwork.

Abri Blanchard likely served as a winter shelter for the first Homo sapiens who arrived in Europe. These early humans, known as the Aurignacians, would have been responsible for the creation of the dotted aurochs. While similar patterns are found in other Aurignacian artifacts, the combination of an animal figure with geometric designs was considered 'exceptional' by researchers.

5. The Hidden Fossil

In 2014, a farmer near Toulouse stumbled upon an unusual discovery. The massive skull resembled that of an elephant, but instead of the typical two tusks, it had four. Fearing that amateur fossil hunters would overrun his land, he kept the find a secret.

A few years later, the farmer contacted the town’s Natural History Museum. The thrilled staff identified the fossil as Gomphotherium pyrenaicum, a relative of the elephant that featured the usual pair of tusks along with an additional pair curving out of its lower jaw.

This species is incredibly rare in the fossil record, with its existence known only from tusks discovered 150 years ago in the same area. These creatures, which roamed the Toulouse region around 12 million years ago, were previously faceless until this skull was unearthed. The find was priceless to researchers, as it provided the species with a face once more after millennia.

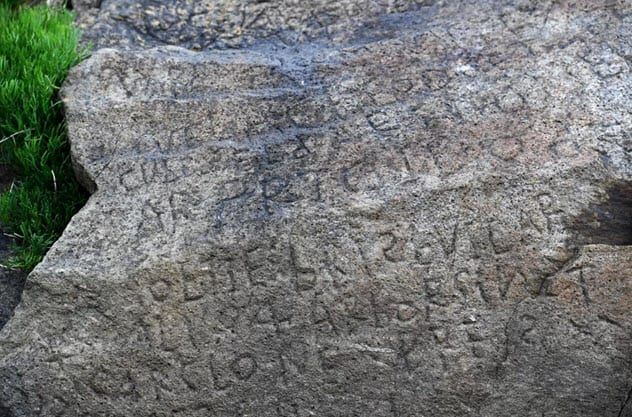

4. The Secret Code

In the northwest of France, in a village called Plougastel-Daoulas, someone walking along a nearby beach made a remarkable discovery. They found a rock with intricate carvings, including symbols of a sailing vessel and a heart. The boulder also displayed a mysterious inscription: “ROC AR B . . . DRE AR GRIO SE EVELOH AR VIRIONES BAOAVEL . . . R I OBBIIE: BRISBVILAR . . . FROIK . . . AL.”

Some of the letters were too unclear to make out, but overall, the message remained indecipherable.

Details are limited. Approximately 230 years ago, someone carved these marks, which are only visible during low tide. The dates 1786 and 1787 were clearly etched into the rock, providing the timeline for the inscriptions.

During that period, artillery batteries were being built to safeguard a nearby fort. However, it’s still uncertain if the creators of the markings had any connection to the fort's construction. In 2019, the village offered a reward of 2,000 euros ($2,240) to anyone who could crack the code of the inscription.

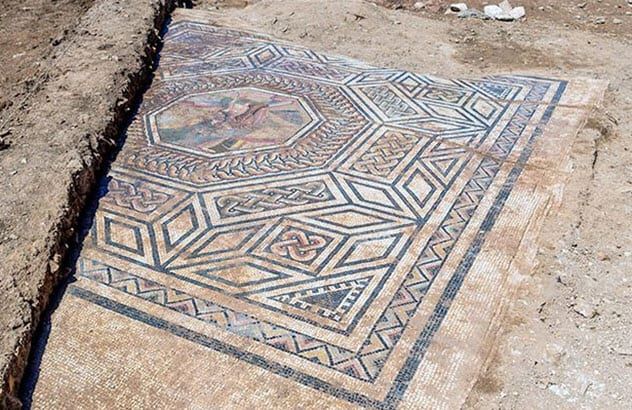

3. A Lost City

The ancient city of Ucetia was known only through an inscription discovered in Nimes, another historical city in France. The name 'Ucetia' appeared on a stela alongside 11 other Roman settlements in the area.

For some time, scholars proposed that Ucetia might correspond to present-day Uzes, a town located to the north of Nimes. In 2016, the construction of a boarding school in Uzes led archaeologists to search the area. Fearing the construction might permanently obscure the lost city, excavations began, and sure enough, they uncovered Ucetia.

By the 2017 excavation season, the site had expanded to 4,000 square meters (43,056 ft), revealing grand structures. Ucetia's origins spanned thousands of years, with the earliest buildings dating back more than 2,000 years, predating the Roman conquest of France.

The city also showed signs of occupation up until the Middle Ages (seventh century). Strangely, it was temporarily abandoned between the third and fourth centuries. One of the most unexpected discoveries was floor mosaics, which were done in a style believed to have been invented 200 years later in the first century AD.

2. A Fire-Preserved Neighborhood

In 2017, a new housing project was planned for a suburb of Sainte-Colombe. As part of the standard procedure, archaeologists were called to survey the area. What they uncovered was nothing short of remarkable.

The excavation unearthed a Roman neighborhood from the first century AD, spanning 7,000 square meters (75,000 ft). The site included houses, artifacts, shops, mosaics, France's largest Roman market square, a warehouse, a temple, and potentially a school of philosophy.

The neighborhood was so well-preserved that it soon became known as 'Little Pompeii.' The settlement had been in use for over 300 years, during which its inhabitants endured two major fires.

The first fire occurred in the second century AD, but it was the catastrophic blaze in the third century that ultimately destroyed the settlement. The fire was so devastating that families fled, abandoning nearly everything. For researchers, however, the heat from the fires provided an unexpected benefit—the extreme temperatures helped preserve the site in remarkable detail.

1. The Body Pit

In 2012, archaeologists uncovered 60 silos, or pits, near Bergheim, a French village close to the German border. One pit, in particular, was truly horrifying. Filled with human remains, this nearly 6,000-year-old pit contained severed arms, fingers, hands, and the remains of seven people.

The brutality of the event spared no one, not even children. A child between the ages of 12 and 16 had their arm hacked off. Among the remains were four children, along with the body of a small infant barely a year old.

One man, middle-aged, endured a particularly brutal death. His arm was severed, and he had suffered multiple blows, including a fatal strike to the head. His remains were discovered at the bottom of the 2-meter-deep (6.5 ft) pit.

At the top of the pit, the scene had changed. Centuries after the massacre, the silo seemed to have been repurposed as a burial site. A woman’s body was laid to rest, but in contrast to the others, there were no marks of violence on her remains. Scholars speculated that the Stone Age community might have been punished for some offense or perhaps perished during a violent conflict.