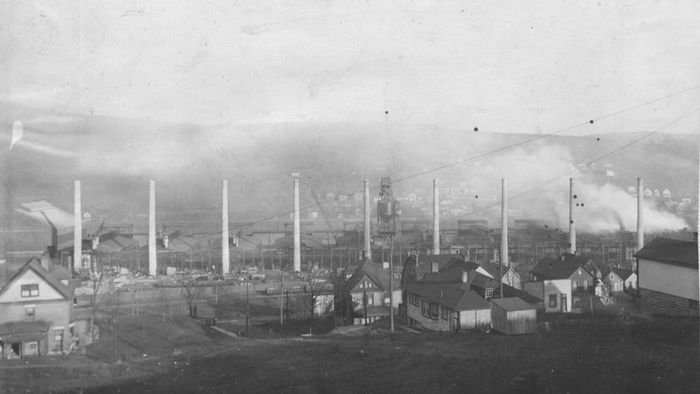

In October 1948, a thick smog enveloped Donora, Pennsylvania, killing at least 21 residents. The disaster sparked a nationwide environmental movement, leading to the eventual creation of the Clean Air Act of 1963. The image shows 9 of the 10 iconic spelter stacks of U.S. Steel’s Donora Zinc Works. Photo credit: Donora Historical Society.

In October 1948, a thick smog enveloped Donora, Pennsylvania, killing at least 21 residents. The disaster sparked a nationwide environmental movement, leading to the eventual creation of the Clean Air Act of 1963. The image shows 9 of the 10 iconic spelter stacks of U.S. Steel’s Donora Zinc Works. Photo credit: Donora Historical Society.In Donora, Pennsylvania, about 30 miles south of Pittsburgh, the former location of a Chinese restaurant now hosts the Donora Historical Society and Smog Museum, a testament to the town's history of air pollution.

Scholars from around the world frequently visit the Donora Historical Society and Smog Museum, a small volunteer-run institution that holds an archive of important documents, blueprints, scientific studies, and rare footage. Volunteer curator Brian Charlton humorously mentions that, on top of his curatorial duties, he also serves as the janitor. 'I was just mopping before I took your call,' he shared during a recent Saturday morning.

The museum's collection continues to captivate attention due to its documentation of one of the most severe pollution disasters in U.S. history— a toxic smog that engulfed Donora in late October of 1948, claiming over 20 lives and leaving thousands more seriously ill. This tragedy is widely believed to have sparked public awareness of the dangers of air pollution, contributing to the establishment of the first federal clean air regulations during the 1950s and 1960s.

A historical analysis published in the American Journal of Public Health in April 2018 highlights how Donora's deadly smog 'transformed the landscape of environmental protection in the United States.'

Donora, a small town with a population of 4,000 today, was once a thriving industrial hub. In 1948, it was far larger, hosting a zinc plant with 10 smelters and a steel mill that used the zinc in its production process. Despite the economic opportunities, working conditions were hazardous. The term 'zinc shakes' referred to the illness caused by prolonged exposure to the substance.

The zinc plant was notorious for emitting vast amounts of pollutants into the atmosphere, including hydrogen fluoride, carbon monoxide, nitrogen dioxide, various sulfur compounds, and heavy metals, all trapped in fine particulate matter, as detailed by the AJPH study.

The nearby village of Webster suffered catastrophic damage to its orchards due to the pollution from Donora. This environmental devastation not only obliterated the livelihoods of local farmers but also caused irreparable harm to Donora’s natural surroundings, with vegetation wiped out and erosion so severe that a local cemetery became an unrecognizable mass of rocks and dirt.

It Crept Up Slowly

No one anticipated that the pollution would become lethal. Then, during the final week of October 1948, the Monongahela-Ohio valley endured an extremely harsh temperature inversion. This weather anomaly trapped the smoke from the industrial plants at ground level in Donora.

Charles Stacey, a Donora resident who was 16 years old and in high school at the time, remembers that the smog that shrouded the town was so dense that, on his walks to school during the mornings and evenings, he struggled to see the traffic signals. 'You had to be careful stepping off the curb,' he recalls.

Initially, he and his friends didn't think much of it. 'We thought the smog was something that had to be,' he says. 'It was part of our heritage.'

However, older individuals and those with preexisting respiratory conditions had a much harder time. By the end of the week, nearly 6,000 people had fallen ill, as later confirmed by federal researchers. Charlton, who reviewed county death certificates from that weekend, documented 21 deaths due to respiratory issues between noon on Friday and 6 a.m. on the following Monday. He believes more deaths likely occurred in the weeks after.

As nearby hospitals were overwhelmed and funeral homes inundated, the old Donora Hotel became a makeshift hospital and morgue. Stacey remembers the hotel's ground floor filled with the sick, while the lower floor was designated for the deceased.

Aftermath

Following the catastrophic event, state and federal health investigators flocked to the town. As noted by Dr. James Townsend of the U.S. Public Health Service in his 1950 account, some residents, fearing retaliation from their employer (the Zinc company), downplayed their illnesses during the smog, while others were more enraged than scared.

In time, many locals filed lawsuits against the company behind the zinc works. The company, in its defense, claimed the smog was an Act of God and thus, it was not liable. According to a 1994 article by Lynn Page Snyder in Environmental History Review, the court required an autopsy for families to participate, likely deterring many from pursuing legal action, says Charlton.

Ultimately, the families settled the case for $250,000, with Charlton explaining, "They were worried they'd end up with nothing."

The tragic loss of life in Donora led to significant change. As Townsend noted, the federal investigation ultimately determined that the harmful effects of the smog were likely due to a mix of pollutants, rather than a single chemical culprit. However, they also found 'considerable evidence' of prior smog events where death rates had surged. The investigation into Donora, Townsend concluded, 'has shown beyond doubt' that the combination of gases and particulate matter in emissions could negatively impact health. He called for further research into the effects of pollution and encouraged industries to reduce emissions.

The Clean Air Act of 1963

As detailed in a 2012 article by Arthur C. Stern in the Journal of the Air Pollution Control Association, just over a year after the Donora Smog, President Harry S. Truman ordered the establishment of a government committee to investigate the air pollution issue. This marked the beginning of a research effort that eventually resulted in the passage of the Clean Air Act of 1963. (Congress would later strengthen the law with the Clean Air Act of 1970.)

By the time the Clean Air Act was passed, the Donora zinc works had already closed. 'People thought it was because they had spoken ill of the plant,' says Charlton. 'They believed for years that they were to blame.' In truth, the plant's closure in 1957 was simply a business decision, prompted by a more efficient process developed by an English company that rendered Donora's smelters obsolete.

The closure of the zinc works — followed by the eventual shutdown of the nearby steel mill a decade later — led Donora into a slow economic decline that the town has yet to fully recover from, according to Charlton. However, the residents of Donora can rightfully take pride in the town's significant role in the battle against pollution.

"One of our mottos is 'Clean Air Started Here,'" Charlton explains. "People look to us as the starting point of the environmental movement, ensuring that industries don’t spiral out of control."

Stacey, a high school student at the time, remembers learning about the death toll when he turned on the radio and heard nationally syndicated columnist Walter Winchell discussing Donora.