Why does a witch outfit always include a pointed hat? What’s the deal with pirates and their overly elaborate, sea-unfriendly accessories? And how did a simple bedsheet become the go-to disguise for a ghost?

The Halloween costumes we adore today carry tales that often stray far from their historical roots. If you ever chat with someone dressed as Batman, you might share how a Renaissance genius influenced the iconic look.

Here’s a dive into the fascinating backstories of five of the most popular adult Halloween costumes, as forecasted by the National Retail Federation. (We’ve left out cats, since their costume inspiration is pretty straightforward.)

Witch

Not alewives. | Betsie Van Der Meer/GettyImages

Not alewives. | Betsie Van Der Meer/GettyImagesThe classic witch attire is often linked to medieval alewives, women who brewed and sold ale or beer. Legend has it that their tall hats helped them stand out in busy marketplaces.

However, this tale is almost certainly a myth.

Judith M. Bennett, in her book Ale, Beer, and Brewsters in England: Women's Work in a Changing World, 1300-1600, highlights how alewives were often portrayed negatively. A late poem from around 1517 describes a fictional alewife engaging in various misdeeds, including interactions with a witch. While it doesn’t outright label the alewife as a witch, the suggestion is likely present.

By 1517, alewives were fading from prominence in England, with Bennett noting that brewing had become a male-dominated industry by 1600. This timing is significant for two reasons: First, the height of witchcraft trials in England was between 1563 and 1712, coinciding with similar trends across Europe. Second, during this period, witches in art were typically depicted as either naked or indistinguishable from ordinary community members. The iconic witch costume didn’t appear until the 18th century, long after alewives had largely vanished. While some alewives may have been accused of witchcraft, they likely didn’t inspire the general witch archetype.

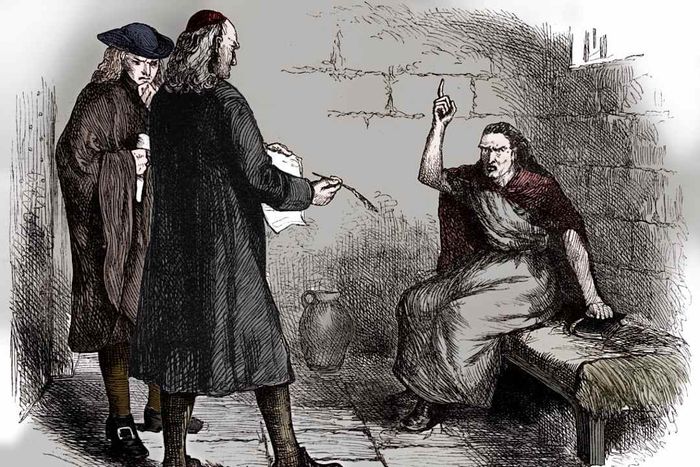

This accused witch is clearly not wearing a black hat. | Print Collector/GettyImages

This accused witch is clearly not wearing a black hat. | Print Collector/GettyImagesThe origins of the witch outfit remain unclear. One theory links it to antisemitism, suggesting the hat resembles headwear forced upon Jewish people in certain regions. Other theories propose it represents a Quaker hat, a capotain (famously known as the “Pilgrim hat”), or even a nod to the goddess Diana.

It’s entirely possible the witch outfit has no profound significance and simply echoes earlier portrayals of witches in ordinary attire. Numerous 17th-century paintings depict women in black robes and tall hats without any association with witchcraft. Some authors argue that during the 17th and 18th centuries, this attire was commonplace. As it fell out of fashion, it became a caricature of rustic, elderly women, eventually evolving into the witch stereotype.

Vampire

Dracula, is that you? | kali9/GettyImages

Dracula, is that you? | kali9/GettyImagesVampires are often depicted as elegant, attractive, and impeccably dressed in tuxedos—unless it’s the original Dracula. In Bram Stoker’s novel, Dracula is portrayed as “a tall old man, clean-shaven except for a long white moustache, dressed entirely in black without a hint of color.” Later, a younger Dracula is described with a black moustache and pointed beard, but “His face was not a good face.”

Smithsonian Magazine notes that the tuxedo look for Dracula originated in the 1924 stage adaptation of the story. To visually convey his seductive powers, the character was portrayed as a handsome man in elegant attire.

This production also introduced the now-famous large collar on the cape, with the cape itself attributed to the stage version. According to author David J. Skal, “The collar initially served a theatrical purpose: hiding the actor’s head when facing away, allowing him to vanish through a trapdoor or wall panel. While the trick collar lost its function in film adaptations, it remains a timeless hallmark of vampire costumes.”

Batman

Yep, he's Batman. | JONATHAN NACKSTRAND/GettyImages

Yep, he's Batman. | JONATHAN NACKSTRAND/GettyImagesBob Kane, co-creator of Batman, has cited numerous inspirations for the character. While Zorro is an obvious influence, Kane also credited The Bat Whispers, a 1930 film about a thief disguised as a giant bat-like figure. Additionally, he drew inspiration from a Leonardo da Vinci sketch called the “Ornithopter,” which he believed gave the wearer a bat-like appearance.

However, Kane’s original design differed significantly from the modern Batman. His version featured a flashier red suit, a Robin-style mask, and bat-like wings inspired by the ornithopter. The iconic Batman look we know today is largely credited to Bill Finger. According to Kane,

“I called Bill one day and said, ‘I’ve created a new character called the Bat-Man and have some rough sketches to show you.’ When he arrived, I presented the drawings, which included a small domino mask similar to Robin’s. Bill suggested, ‘Why not make him more bat-like with a hood, slits for eyes, and a darker, more mysterious appearance?’ Initially, the Bat-Man wore a red outfit with black wings and trunks. Bill thought the colors were too bright and recommended dark gray for a more ominous look. The cape, originally stiff bat wings, was redesigned to resemble bat wings when in motion. We also added gloves to avoid leaving fingerprints.”

While many other influences shaped Batman—early stories and artwork were often reworkings of existing media—and the character has evolved over time (notably the chest logo, which has changed dramatically), Finger’s design played a pivotal role in creating one of the most iconic superheroes in history.

Pirate

Ahoy, matey. | Mordolff/GettyImages

Ahoy, matey. | Mordolff/GettyImagesCompare these two images: The first hardly resembles a pirate. Aside from the hat, guns, and smoke, little about it feels out of place in modern times. The second image, however, screams piracy with its headscarf, sash, baggy pants, and even an earring upon closer inspection.

Both are artistic portrayals of Blackbeard, but the first dates back to the 18th century, shortly after his death (though not necessarily entirely accurate), while the second is from the early 20th century. The transformation is largely attributed to one man: Howard Pyle.

Pyle, a late 19th and early 20th-century illustrator, worked during a time when Golden Age pirates became popular in comic operas and stories like Treasure Island and Peter Pan. Inspired, he chose to depict pirates in his art but avoided historical archives for research. He believed his illustrations should be self-explanatory, famously saying, “Don’t make it necessary to ask questions about your picture. It’s impossible for you to visit every newsstand to explain your work.”

Staying true to his philosophy, Pyle sought inspiration from unconventional sources for his pirate depictions.

According to Anne M. Loechle’s Ye Intruders Beware: Fantastical Pirates in the Golden Age of Illustration, Spain was seen as exotic by 19th-century Americans and much of Europe. It was a favored spot for artists and travel writers, whose descriptions often mirrored modern pirate imagery, featuring sashes, baggy pants, and headscarves. Pyle likely embraced Spain’s exotic allure when designing his pirate costumes.

Captain William Kidd, illustrated by Howard Pyle. | Culture Club/GettyImages

Captain William Kidd, illustrated by Howard Pyle. | Culture Club/GettyImagesThere’s more to the story. Pyle worked during rising tensions between Spain and the United States. Pirates, in contrast to the era’s stereotypical white Navy men, were portrayed as racially ambiguous. Loechle writes, “The pirate’s maritime world, shared with the U.S. sailor, highlights their stark differences: the sailor is white, while the pirate’s headscarf, sash, short pants, and swarthy complexion make him resemble Spanish gypsies. This racial and national ambiguity likely contributed to the pirate’s popularity in American art.”

Pyle wasn’t solely an illustrator; he also mentored other artists. Many of his students followed his lead, creating iconic pirate imagery that cemented 19th-century Spanish-inspired designs as the quintessential American portrayal of pirates.

Ghost

A simple yet effective Halloween costume. | Cavan Images/GettyImages

A simple yet effective Halloween costume. | Cavan Images/GettyImagesThe classic bedsheet ghost is often linked to Renaissance burial traditions. During that era, individuals were wrapped in a shroud or winding sheet, frequently without a coffin.

The bedsheet ghost transitioned to the stage in the early 16th century. Initially, ghost characters were barely distinguishable from others, aside from flour used to whiten their faces. By the late 16th century, a visual language developed, with white sheets symbolizing ghosts. According to Karen Quigley’s Performing the Unstageable: Success, Imagination, Failure, in Shakespeare’s Richard III, actors playing ghosts often had multiple roles and used sheets as a quick costume change.

While today’s audiences see the bedsheet ghost as a humorous, low-effort Halloween costume, its historical counterpart was far more ominous—deadly serious, in fact.

From the 16th to 19th centuries, ghost impersonators often met grim fates, whether beaten nearly to death or robbing their victims. A notable case from 1704 involves thief Arthur Chambers, who faked his brother’s death to bring a coffin into a house he planned to rob. Wrapped in a winding sheet and dusted with flour, he emerged from the coffin, terrifying a maid who screamed, “a Spirit, a Spirit!” Chambers escaped with 600 pounds’ worth of stolen goods.

Chambers, according to an 18th-century account, “rose from his mansion of death . . . and went downstairs into the kitchen, sitting opposite the maid in his winding sheet. Her terror led her to scream, ‘a Spirit, a Spirit!’” Chambers successfully stole valuables worth 600 pounds.

How did such a terrifying image become comedic? Owen Davies, in The Haunted: A Social History of Ghosts, explains that 1920s and ‘30s comedians drew inspiration from these hoaxes. Films like Laurel and Hardy’s Habeas Corpus and Buster Keaton’s Neighbors featured characters mistaken for ghosts after being covered in sheets, eliciting laughter from audiences despite the on-screen terror.

Davies notes, “The slapstick ghost stripped the white sheet of its ability to frighten. While countless people still believe in spirits roaming the earth, encountering a white sheet on a dark night would rarely prompt anyone to exclaim, ‘Ghost!’ Laurel and Hardy played a key role in ending that fear.”