With crowds stretching around the block, Bob Burns' Halloween creation for 1979 was set to surpass his previous spectacles, like the massive eyeball on his roof or the chilling The Exorcist tribute featuring his wife Kathy “floating” above a bed. It even outshone his crashed spaceship setup, complete with menacing Martians and actors armed with ray guns.

A film editor by profession, Burns was a devoted Halloween enthusiast. From 1967 to 1979, he transformed his Burbank bungalow into a series of increasingly intricate haunted house experiences, spilling into both his front and back yards. These displays, precursors to modern high-tech attractions, captivated the community so much that the candy he distributed became a mere footnote.

In his memoir, Monster Kid Memories, co-authored with Tom Weaver, Burns fondly recalled his final haunted house as his masterpiece. It featured a spine-chilling spaceship corridor, a missing cat, and a sudden encounter with the acid-dripping Xenomorph that had haunted audiences earlier that summer.

Soon, whispers spread through the lengthy queue: A woman had fainted in Bob Burns' terrifying haunted yard.

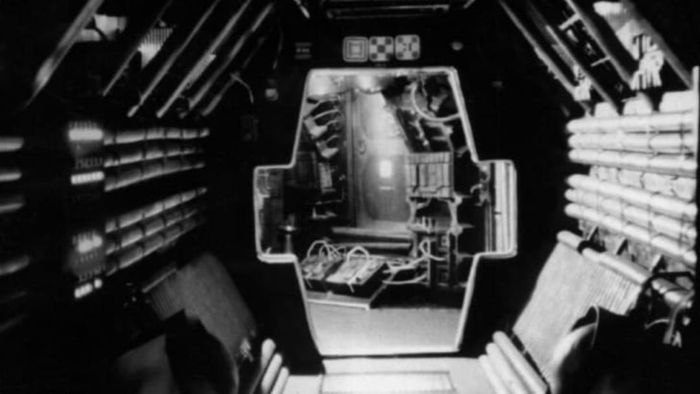

The 'Nostromo' spaceship corridor, created by Bob Burns and his friends for his 1979 backyard Halloween attraction. | Courtesy of Bob Burns

The 'Nostromo' spaceship corridor, created by Bob Burns and his friends for his 1979 backyard Halloween attraction. | Courtesy of Bob BurnsWhile Burns didn’t pioneer the idea of home-based haunted attractions, he undoubtedly elevated it to new heights. During the Great Depression, such displays were meant to deter mischievous children from causing trouble. Families would transform basements into eerie spaces, dangling raw liver or wet sponges to startle brave visitors. Disney’s Haunted Mansion in 1969 brought the concept to the mainstream, using advanced effects far beyond simple gore. Today, haunted attractions are a booming industry, with over 4000 venues generating $300 million each year.

Profit was never Burns' goal: He never charged admission. A lifelong “monster kid” captivated by creature films and special effects, Burns pursued a career in the film industry, eventually becoming a film editor at KNXT, a CBS affiliate in Los Angeles. In his spare time, he befriended effects artists who shared his love for props. His home museum housed treasures like the original skeleton model from 1933’s King Kong and aliens from Star Wars’ Cantina scene. Some props came from collectors or studios, while others were gifted by those who knew he’d cherish them.

“He turned his home into a museum to showcase his incredible collection of memorabilia,” actor Walter Koenig (Star Trek), a friend of Burns, shared with Mytour. “Our shared passion for comic character collectibles brought us together. He’s incredibly warm-hearted and a joy to spend time with.”

Burns’ charisma and genuine enthusiasm shone through when he decided to go beyond handing out candy for Halloween. In 1967, he created a mad scientist lab in his living room, complete with a buzzing neon transformer hovering over a Frankenstein-like dummy. (The transformer even disrupted his neighbors’ TV signals.) By 1970, he collaborated with friends to build “Goombah,” a massive tentacled eyeball perched on his roof, visible from blocks away. Inside, visitors watched an actor wrestling with a tentacle, yelling, “It’s eating my brain!”

While some of his displays were playful, others were genuinely horrifying. In 1974, Burns unveiled “The Thing in the Attic,” a chilling depiction of demonic possession. Special effects maestro Rick Baker, later an Oscar winner for films like An American Werewolf in London, helped create a scene where Burns’ wife, Kathy, appeared to levitate 4 feet in the air, her eyes glowing with battery-powered red bulbs. Burns would then plunge the room into darkness and charge into the crowd as a masked demon, repurposing a Cantina prop. The screams from neighbors lasted for hours.

Over the years, Burns became a local legend. His events were covered by news outlets, and he started drawing nearly 3000 visitors each year. In 1978, sci-fi magazine Starlog featured Burns in a detailed article about his Halloween passion and the intricate attractions he built. The piece served as a seal of approval, which Burns later shared with 20th Century Fox publicists during their visit to KCBS in 1979 to promote their new horror film, Alien.

Directed by Ridley Scott and starring Sigourney Weaver as Ellen Ripley, the sole survivor of a spaceship crew hunted by a deadly alien, Burns saw the film as the ideal inspiration for his final Halloween spectacle. To his delight, Fox allowed him to recreate the Nostromo ship and the iconic creature designs by H.R. Giger. They even lent him film props, including the mechanical “face hugger” that attached to victims’ faces to incubate the alien offspring.

With Fox’s approval, Burns and his team—including Dorothy Fontana, a former writer for the original Star Trek series—spent weeks constructing a detailed corridor over his driveway and into his backyard. Using pipes and valves, they recreated the film’s tense, confined atmosphere. For the role of the ship’s ill-fated captain, Burns recruited Walter Koenig, who was preparing to reprise his role as Pavel Chekov in the first Star Trek movie. Despite concerns about asking Koenig to volunteer, the actor happily agreed.

“He offered me the role of the captain, and I’ve always wanted to command something, so I agreed,” Koenig recalls. “I didn’t realize how physically demanding it would be until after the fact.”

For the grand finale, Burns borrowed the actual alien head from the film’s iconic costume. (He crafted the rest of the body himself.) A neighbor, Tom De Veronica, volunteered to wear the outfit, delivering a shocking surprise to the backyard audience.

By Halloween, rumors spread that Burns had outdone himself, and longtime fans camped out on the street to secure a spot. Several Fox executives also attended, curious to see how Burns’ DIY approach would bring their prized film to life.

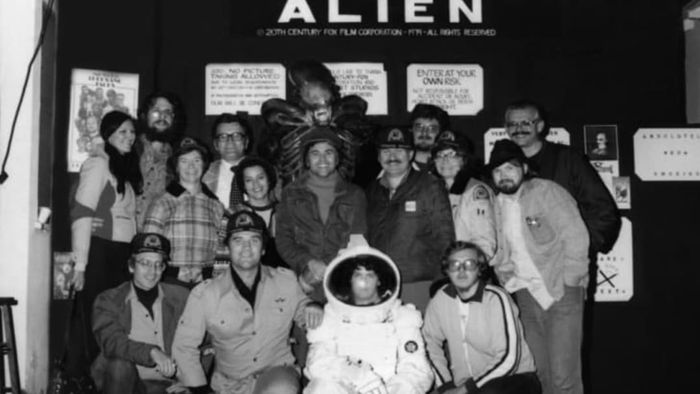

The team behind Bob Burns’ 1979 'Alien' attraction. Burns is in the middle row, third from the right. | Courtesy of Bob Burns

The team behind Bob Burns’ 1979 'Alien' attraction. Burns is in the middle row, third from the right. | Courtesy of Bob BurnsAccording to Koenig, the entire sequence lasted only two to three minutes. As the Nostromo captain, he led the audience down the corridor, announcing that his motion detector had picked up strange activity. Claiming it might be the ship’s cat, Koenig climbed a ladder and vanished—only to reappear moments later, wrestling with the face hugger that had latched onto his head.

As the crowd reeled from the shock, De Veronica burst out from a hidden panel, catching everyone off guard. Spectators leaped in fear; one woman even fainted. (“Today, we’d probably face a lawsuit,” Burns later remarked.) For a haunted attraction, it was the ultimate seal of approval.

“We performed it at least 50 or 60 times,” Koenig recalls. “I even brought in one of my acting students to share the workload. The screams were deafening, and people waited in line all night.”

The Fox executives were so impressed with Burns’ work that when he offered to return the props, they insisted he keep them—not just the borrowed items but additional pieces from the film. Soon, a truck arrived at his home, delivering a 12-foot model of the Nostromo used in the movie.

“Bob never settled for amateur work,” Koenig explains. “Everyone involved was a seasoned professional from the industry.”

The Alien costume from the 1979 Halloween spectacle | Bob Burns

The Alien costume from the 1979 Halloween spectacle | Bob BurnsThat professional quality eventually marked the end of Burns’ Halloween tradition. As friends like Baker and Dennis Muren—who gained fame working on Star Wars—became consumed by their careers, Burns struggled to assemble his usual team for his intricate displays. Since 1979, he’s staged only two more: a 1982 homage to Creature from the Black Lagoon and a 2002 show inspired by The Thing. Directors like Guillermo del Toro, Frank Darabont, and Rob Zombie attended what may have been his final performance.

Now 82 and living in Burbank, Burns continues to preserve and showcase his extensive memorabilia collection. While modern haunted houses boast large budgets, few can match the heartfelt passion that transformed his street into a Halloween hotspot for over a decade.

“The Alien attraction truly cemented Bob Burns’ legacy,” Koenig remarks. “Many of his friends put in hours of hard work simply for the joy of it.” Though Koenig didn’t participate in constructing the Nostromo corridor, he adds, “Burns likely could have persuaded me to help if he’d asked.”

Additional Sources: Monster Kid Memories