As the cornerstone faith of both the Western and Eastern empires, Christianity has inspired countless literary works rooted in its teachings and values. This list explores ten of the most exceptional writings crafted from a Christian worldview.

10. A Wrinkle in Time Madeleine L’Engle (1962)

This novel earns its place on the list for its unique blend of science and Christianity, two fields often perceived as conflicting. In L’Engle’s story, the protagonist, Meg Murry, and her scientifically gifted family uncover a method to bend space-time, enabling instantaneous travel across the Universe. Their journey takes them to Uriel, a heavenly planet filled with goodness and angelic centaurs singing in harmony. There, they learn of a cosmic threat known as the Black Thing, which has engulfed the planet Camazotz. This dark force, ruled by a disembodied intelligence called IT, enforces absolute conformity, erasing individuality and creativity. Meg’s father, a scientist working on faster-than-light travel, has been captured by IT, and the family must confront this oppressive force to save him and restore balance.

As the story unfolds, Meg and her family encounter three extraordinary immortal beings: Mrs. Which, Mrs. Whatsit, and Mrs. Who, each possessing distinct traits. Mrs. Who, fluent in multiple languages, often cites Shakespeare and biblical passages. Their journey leads them to Camazotz, where Meg’s brother falls into the clutches of IT. While the others manage to escape, Meg later returns to save her brother after discovering IT’s vulnerability to the power of love. The experience leaves them with profound insights on living virtuously and treating others with kindness.

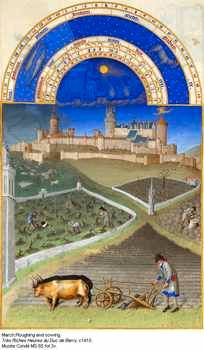

9. Piers Plowman William Langland (c. 1370)

This allegorical tale features characters whose names reflect their traits or emotions. Set in Malvern Hills, Worcestershire, the protagonist, Will (symbolizing free will), dreams of a hilltop tower and a valley fortress, representing Heaven and Hell, with a “fair field full of folk” symbolizing humanity in between. Will embarks on a quest to reach the tower, guided by Piers, a plowman, who teaches him about Truth. Along the way, Will seeks companions named Dowel (Do Well), Dobet (Do Better), and Dobest (Do Best), exploring how a Christian should live according to Catholic teachings.

8. The Canterbury Tales Geoffrey Chaucer (c. 1390)

This work is ranked lower on the list because, while it addresses Christianity in post-Black Death England, its primary focus is critiquing the societal norms of that era. However, its deep reliance on Christian philosophy and moral principles secures its inclusion here. The narrative follows a diverse group of travelers, including a knight, miller, cook, friar, and nuns, who meet on their pilgrimage to Canterbury Cathedral to visit Thomas Becket’s shrine. To pass the time, they engage in a storytelling contest, with each tale reflecting the Catholic Church’s teachings and societal issues of the time.

Chaucer penned this masterpiece during the Great Schism, a period of division within the Catholic Church from 1378 to 1417. The schism saw rival popes in Rome and Avignon, France, each claiming authority. The conflict was eventually resolved through a council, excommunications, and the election of a new pope in Rome. The tales in the work showcase a range of theological perspectives and disagreements, yet the characters remain united on their journey to Canterbury. Chaucer uses this pilgrimage as a metaphor for Christianity’s ability to unite its followers, regardless of their differing views.

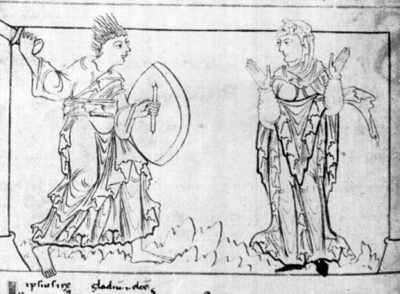

7. Psychomachia Aurelius Prudentius Clemens (c. 400)

The term “Psychomachia” translates to “Battle for the Soul.” This work earns its high ranking, despite its relative obscurity, as one of the earliest Christian allegories, possibly the first. Written as an epic poem spanning roughly 1,000 lines, it mirrors the style of Virgil’s Aeneid, depicting an intense struggle between virtues and vices within an unnamed character, symbolizing the reader. The poem features the classic deadly sins and cardinal virtues, though not in their modern formulations. The conflict begins with Pagan idolatry, introducing Pride, which is vanquished by Selflessness, and so forth. The climactic battle pits Hatred and Wrath against Love, with Love ultimately triumphing in the name of Christ Jesus. The poem concludes with 1,000 Christian martyrs singing praises of Faith with a resounding Hallelujah.

6. The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe C. S. Lewis (1950)

Lewis’s entire Narnia series is rich with Christian symbolism, but the first and most renowned book stands out as the most overt, offering a creative retelling of Jesus’s life. The name “Aslan” means “Lion” in Turkish. Lewis enchants readers with a magical world filled with talking animals, mythical beings like centaurs, unicorns, and tree spirits akin to Tolkien’s ents. Narnia is under the oppressive rule of Jadis, the White Witch, who has plunged the land into perpetual winter, banishing Christmas forever.

Four children from Earth stumble into Narnia, only to learn their arrival was foretold and signals the return of Aslan, destined to restore justice. Along their journey, Aslan imparts lessons on virtue and sin, addressing the misdeeds of one child, Edmund. The Witch demands Edmund’s life as punishment for betraying his siblings, but Aslan sacrifices himself in the boy’s place. The Witch believes this act of Deep Magic will secure her dominion over Narnia, but she is gravely mistaken.

5. A Christmas Carol Charles Dickens (1843)

Many scholars argue that Christmas has become the world’s most beloved holiday today, not solely due to the Nativity narrative, but largely because of its resurgence in Dickens’s mid-Victorian novella, which champions universal charity, transcending religion, social status, and other divides. Dickens suggests that, in a secular sense, Christmas should embody selfless giving and unity, a time when humanity sets aside differences to embrace a spirit of brotherhood.

Ebenezer Scrooge, a detestable miser and money lender, refuses to part with his wealth unless he profits. He loans money only to those he deems capable of repayment, imposing exorbitant interest rates and harsh penalties for late payments. He shows no compassion for the poor or those struggling to survive. However, his life takes a dramatic turn on Christmas Eve when he is visited by the ghost of his former business partner, Marley, who warns him of impending damnation. Subsequently, the spirits of Christmas Past, Present, and Future reveal the consequences of his selfishness. Transformed by these visions, Scrooge embraces generosity, leading to a joyous Christmas Day and a brighter future for all.

The story’s influence has permeated global culture. Terms like “Scrooge” have become synonymous with miserliness, and the phrase “God bless us, everyone” is now a widely recognized expression of goodwill.

Is the story explicitly Christian? Absolutely, as even in a secular context, the term “Christmas” inherently ties to Christ, and Dickens deliberately chose this holiday over others. Through this, the themes of universal charity, generosity, and love are invoked in Christ’s name, reinforcing its Christian foundation.

4. The Pilgrim’s Progress John Bunyan (1678)

This work stands as the most overtly allegorical of all Christian tales. The protagonist, named Christian, reads the Bible and becomes weighed down by a heavy backpack symbolizing the burden of his sins. One day, he encounters Evangelist, who guides him toward the Wicket Gate. Abandoning his family and home, Christian embarks on a quest for salvation, fearing eternal damnation in Tophet (Hell), a place historically linked to child sacrifices to Moloch in ancient Jerusalem. Along his journey, he faces temptation from Mr. World Wiseman, who urges him to seek redemption through earthly laws. Christian resists, reaches the gate, and meets Good Will, who directs him further. At Calvary, his backpack’s straps break, freeing him from his burden. In the second part, Christian’s family follows his path, achieving salvation and reuniting with him in Paradise. Good Will is revealed to be Jesus.

3. La Divina Commedia Dante Alighieri (1308-21)

The Divine Comedy stands as the pinnacle of Italian literature, a remarkable achievement given the language’s rich literary history. While determining the greatest work in English or other languages is challenging, Dante’s masterpiece unquestionably dominates Italian literature. He introduced terza rima, a unique rhyme scheme, specifically for this epic poem, a structure that remains influential today. Despite its title, the Comedy contains no humor; it is a “comedy” because Dante, the protagonist, ascends from Hell through Purgatory to Heaven, culminating in a joyous conclusion rather than a tragic one.

The most renowned section, the Inferno, spans 34 cantos filled with vividly imaginative and terrifying depictions of punishment. Unlike the modern Christian image of a lake of fire, Dante’s Hell features intricate, sin-specific torments. Organized into nine circles, Hell blends elements of Ancient Greek and Roman underworlds with Christian theology. It houses popes, cardinals, and those who lived before Christ’s sacrifice redeemed humanity. The Harrowing of Hell is referenced early on, explaining how Old Testament figures like Noah, Abraham, Moses, and King David were saved and brought to Heaven.

The poem serves as a critique of prominent historical and contemporary figures. Dante places those he admired, such as Homer, Virgil, Horace, Ovid, and Lucan, in Limbo. Julius Caesar and Saladin, known for their decency and chivalry, also reside there. However, Alexander the Great endures eternal torment in Phlegethon, a river of blood in the seventh circle. The poem’s macabre imagery extends to lawyers, who are submerged in a sea of boiling pitch.

With its breathtaking imagery and subtle yet profound moral lessons, Dante’s work captivates readers from start to finish. Its brilliance and educational depth, conveyed without overt didacticism, firmly establish The Divine Comedy as a timeless masterpiece deserving of the highest acclaim.

2. Paradise Lost John Milton (1667)

This epic poem is not an allegory but a profound theological exploration, masterfully addressing why God permits suffering, the origins of sin, and the necessity of Jesus as the Messiah. Milton delves deeply into philosophical questions, particularly when God, observing from Heaven, explains humanity’s fall from grace after disobeying His command (to avoid eating from the forbidden tree). With mankind now fallen, the Son of God, still in Heaven and not yet incarnated on Earth, declares to His Father that He will descend, become human, and sacrifice Himself to redeem humanity’s sins.

Satan is portrayed as one of literature’s most intriguing characters, almost serving as the poem’s protagonist from his perspective. Cast out of Heaven for rebelling against God, Satan aspires to usurp God’s throne and refuses to surrender. Now in Hell, he and his followers plot revenge. While some advocate for open warfare, Satan opts for subtle treachery: he learns of God’s newest creation, mankind, and resolves to corrupt it, aiming to inflict despair upon God. His malevolence is chilling.

One of the poem’s most thrilling moments is a flashback to the celestial war in Heaven. The narrative raises questions about how immortals can be defeated, but the focus is on the battle itself. Satan and his angels clash with Michael and his forces, with the victors claiming Heaven’s throne and banishing the losers to Hell. Michael’s angels are nearly overwhelmed, but the Son of God intervenes, riding a chariot of divine fire to turn the tide. This dramatic scene, akin to a cinematic climax, showcases the Son’s power and resolve.

1. The Faerie Queene Edmund Spenser (1590-96)

This epic poem is arguably the longest in the English language, and Spenser envisioned it being twice or even four times its completed length. Comprising six books, each dedicated to a specific virtue—holiness, temperance, chastity, friendship, justice, and courtesy—the first book remains the most renowned. Spenser’s leisurely narrative style, which takes considerable time to convey its messages, often leads readers to stop after the first book. He also introduced the Spenserian stanza for this work. The protagonist of the first book is the Redcrosse Knight, representing King George of England, with the red cross symbolizing the English flag.

The Redcrosse Knight embarks on adventures across the English countryside, rescuing Una, a damsel symbolizing both Queen Elizabeth I and the Virgin Mary. Accompanied by a lion (representing God’s law) and a lamb (symbolizing God’s love), Una enlists the knight to save her family’s castle from a dragon (Satan). After donning the armor of God, the Redcrosse Knight defeats the dragon in a climactic battle, one of the poem’s most iconic moments. Along their journey, they encounter various antagonists, including Duessa, representing the false Church, and Archimago, a sorcerer embodying pagan heresy and hostility toward Redcrosse and England. The tale also features appearances by King Arthur and Merlin.