As we approach the 105th anniversary of the Titanic's fateful sinking, the ship’s story remains firmly embedded in our cultural consciousness. Over the years, countless myths and tales have been passed down about the ship and its passengers. While some hold elements of truth, others have been widely distorted and now form part of the mythic narrative. Here are ten prevalent misconceptions surrounding the Titanic and its tragic end.

10. The First SOS Signal

One of the most persistent Titanic myths that still catches many trivia enthusiasts off guard is the belief that the Titanic was the first ship to use the 'SOS' distress signal. Like most myths, this one contains a kernel of truth, but it has been exaggerated into a more dramatic narrative. The myth originates from a conversation between Titanic's wireless operators, Harold Bride and Jack Phillips, following the ship's collision with the iceberg. Bride humorously suggested that Phillips seize the chance to use the new 'SOS' distress call, as it might be his last opportunity to send it.

Before the Titanic's sinking, there was no standardized international distress call for ships in danger. British ships typically used the 'CQD' signal, which stood for 'SEEK YOU—DANGER/DISTRESS.' In 1906, a wireless communication conference aimed to eliminate the confusion by establishing a universal distress call. They settled on 'SOS,' which, contrary to popular belief, had no particular meaning. The letters were selected because they were simple to transmit and easy to recognize, even for inexperienced operators.

Despite the introduction of 'SOS,' many operators preferred to stick with the familiar 'CQD,' and Titanic was no exception. After the collision, Phillips initially sent out 'CQD,' before Bride suggested using 'SOS' as well. While 'SOS' was still a relatively new signal in 1912, it had been in use for several years prior to the disaster (though it wasn’t the first choice of many operators). Titanic's use of 'SOS,' however, marked a significant moment in the wider adoption of the signal by British ships. Today, 'SOS' remains a globally recognized distress signal.

9. The Lookouts Didn’t Spot The Iceberg Because They Were Lacking Binoculars

It has long been known that Titanic's lookouts lacked binoculars during their fateful voyage, with the common belief being that had they had them, they might have seen the iceberg in time to prevent the disaster. This claim was echoed by Lookout Frederick Fleet during the British inquiry into the sinking, where he stated that the absence of binoculars was a significant factor. But is this really the case? And if so, why weren't the lookouts provided with binoculars?

In fact, Titanic's lookouts were originally meant to have binoculars. The ship had a designated storage space for them in the crow’s nest. Typically, binoculars were locked up when a ship was in port, but would be given to the lookouts once the voyage began. However, when Titanic set sail from Belfast, the binoculars were missing, so the second officer lent his own pair to the lookouts. When the ship reached Southampton, the second officer asked for his binoculars back and locked them in his cabin. Shortly before Titanic departed Southampton, a last-minute officer change occurred, and the new second officer informed the lookouts that no binoculars would be provided. Despite their requests after leaving Queenstown, the binoculars never turned up.

Testimony during the inquiries revealed a divided opinion about the need for binoculars for lookouts. It seemed that the White Star Line's practice of providing binoculars was more of an exception than a rule. When they were provided, it was usually during bad weather conditions, which, of course, was not the case the night Titanic struck the iceberg. Many people argued that binoculars were unnecessary or even hazardous for lookouts, as focusing on a single point on the horizon would limit their peripheral vision. Some lookouts even stated that they would only use binoculars if they first spotted an object with their naked eye, simply to get a clearer view. After all, the lookout’s job wasn’t to identify objects, but to spot hazards and notify the officers on the bridge, who would then determine what the object was.

It’s easy to understand why Frederick Fleet, who feared being blamed for the disaster, would claim that binoculars could have helped avoid the tragedy. However, in reality, it seems unlikely that binoculars would have made a difference. If Fleet had seen the iceberg and used the binoculars to identify it, the delay in warning the bridge would have been even longer. Even if he had been using the binoculars, whether or not he was looking at the exact right spot on the horizon at the right moment would have been purely a matter of chance.

8. The Curse of Amen-Ra's Mummy

A widely known urban myth suggests that the Titanic's cargo hold contained the cursed Mummy of Amen-Ra, which supposedly caused a series of misfortunes, leading the ship directly into the iceberg's path. However, there was never any such mummy aboard the Titanic. The tale itself exemplifies the numerous myths and legends that have emerged around the Titanic disaster.

During the ill-fated journey, renowned spiritualist William T. Stead captivated his dinner guests with the tale of Amen-Ra’s mummy, which was, at the time, on display at the British Museum. After the Titanic sank, the narrative began to shift, and soon the story transformed, placing the mummy aboard the ship instead of in the museum.

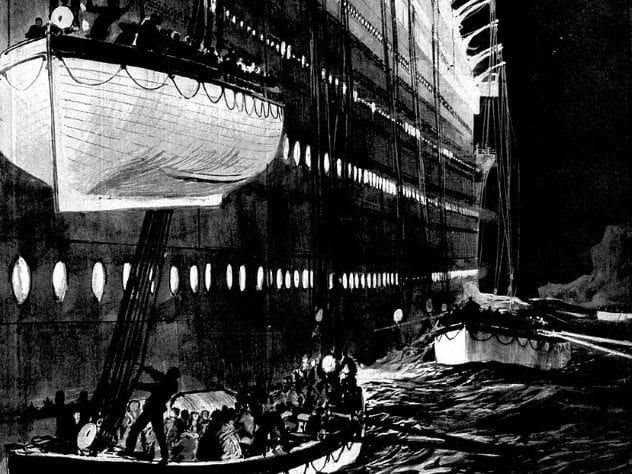

7. The Lifeboat Myth: If Only There Had Been Enough, Everyone Would Have Survived

It’s widely known that Titanic didn’t have enough lifeboats to accommodate all its passengers. At the time Titanic embarked on its fateful journey, regulations stipulated the ship required only 16 lifeboats. In reality, Titanic exceeded this requirement, carrying an additional four smaller boats, known as 'collapsibles.' The myth that lifeboats were deemed unnecessary on an 'unsinkable' vessel is, however, inaccurate. But had Titanic carried sufficient lifeboats for everyone aboard, would it truly have prevented the staggering loss of life?

The short answer is ‘no,’ and there are several reasons for this. First, the final lifeboats were launched (or more accurately, swept off the deck) around 2:15 AM, just five minutes before the ship completely sank. This left officers with insufficient time to launch and lower the lifeboats they did have. Eyewitness accounts also indicate that many passengers hesitated to board the lifeboats, thinking they would be safer on the ship. Some had to be persuaded, while others outright refused. Moreover, third-class passengers struggled to reach the lifeboats, with some never finding them at all.

The storage of the lifeboats presented additional challenges. For instance, Collapsible C couldn’t be launched or even set up until Boat 1 had been lowered. Collapsibles A and B were stored on the roof of the officers’ quarters, requiring significant time to bring them down to the boat deck for loading. It’s likely that other lifeboats were stored in similarly difficult-to-reach areas, and the crew simply didn’t have enough time to prepare and load them before the ship sank.

Although it’s true that with the calm sea conditions, a few additional lifeboats might have been beneficial in the water (if they had been freed in time), it’s evident that even if Titanic had carried enough lifeboats for everyone, the death toll would still have been tragically high. That night, time itself was as merciless to the souls on board as the freezing waters below.

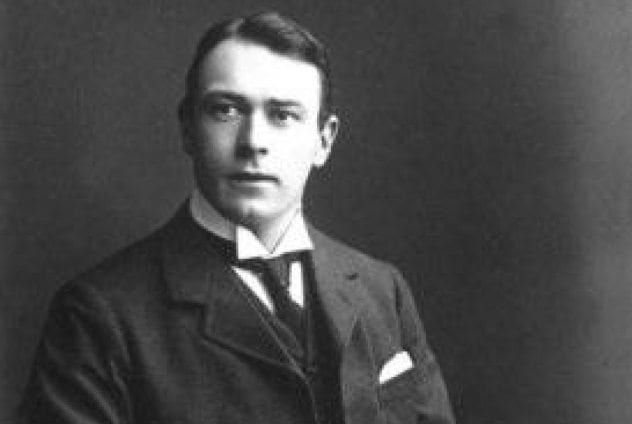

6. The Last Moments of Thomas Andrews

Thomas Andrews, the shipbuilder, is often hailed as one of the Titanic disaster’s heroes. Yet, it’s interesting how legend has shaped his final moments into a romanticized scene—one where he’s seen standing alone in the first-class smoking room, gazing at a painting of Plymouth Harbor, a life belt draped over a chair, symbolizing hopelessness rather than survival. This vivid image, derived from eyewitness accounts, has become iconic. But did Thomas Andrews truly meet his end in this way?

The steward in question was John Stewart, and while there is little reason to question his account, the timing of his sighting raises doubts about the final moments of Thomas Andrews. Stewart was likely saved in Boat 15, which left the Titanic around 1:40 AM, meaning his observation of Andrews in the smoking room took place at least 40 minutes before the ship actually sank.

There are additional reports of Andrews being seen later that provide more insight into his final moments. One anonymous survivor described seeing Andrews on the boat deck during Titanic's final moments, throwing deck chairs overboard to provide something for those trapped in the freezing waters to cling to. Mess Steward Cecil William N. Fitzpatrick also saw Andrews on the bridge with Captain Smith as Titanic made her last plunge. Reportedly, Captain Smith told him, 'We cannot stay any longer—she is going!' The two then dove into the water together.

It appears, then, that instead of succumbing to despair, Thomas Andrews spent his final moments trying to save others. As his biographer Shan F. Bullock noted in 1912, 'Whatever he saw in that quiet, lonely minute it did not hold or unman him. Work—work, he must work to the bitter end.'

5. Third-Class Passengers Were Trapped Below Decks

The image of third-class passengers simultaneously battling for their lives and the class system is a recurring theme in Titanic films. This notion, though dramatic, has roots in truth. Of the approximately 700 third-class passengers, only about 180 were rescued, and there are accounts of some groups deep within the ship being blocked from reaching the boat deck. This is shocking, but it’s important to consider the full context of the situation.

In 1912, immigration laws required strict class divisions aboard ships to prevent the spread of disease. On open decks, low-hinged gates separated the classes, and signs were posted throughout the ship. In the ship’s interior, tall Bostwick gates (like those seen in James Cameron’s movie) were used, as class sections were often interchangeable. These gates helped maintain separation, but how often they were actually locked is another matter. Stewards were tasked with ensuring no one ventured into the wrong part of the ship.

On the night of the disaster, many passengers, crew, and even some officers didn’t fully grasp the gravity of the situation. Even those who knew Titanic was sinking were hearing rumors of rescue ships arriving soon, in some cases within the hour. Many passengers assumed normal rules still applied and chose to stay in their designated parts of the ship, believing everything was under control.

The idea that there was a deliberate effort to prevent third-class passengers from reaching the boat deck seems plausible if we picture the Bostwick gates blocking their only escape route. However, this wasn’t the reality. Third-class passengers had easy access to open decks. In fact, common areas like the third-class smoking room, which passengers were familiar with, were located near these decks. Eyewitnesses reported seeing numerous third-class passengers making their way to these open decks.

Unfortunately, there were very few signs guiding passengers to the upper decks, a challenge made worse by the number of third-class passengers who couldn’t speak English. Although some stewards assisted third-class passengers in finding their way, it’s easy to imagine how difficult this would have been, especially for those who attempted it alone. Despite this, many managed to find their way. The real difficulty arose when trying to access the second- and first-class areas on the upper decks, where we hear stories of people being blocked from reaching the boat deck. However, evidence suggests that many third-class passengers did manage to reach the boat deck—but not until the final hour of the disaster.

The notion that there was a deliberate conspiracy to let third-class passengers perish is, quite frankly, absurd. The reality is that a combination of misguided beliefs about the ship’s safety from both passengers and crew, the complexity of navigating the ship’s layout, language barriers, and disorganization were the main contributors to the disproportionate loss of life in third class.

4. Titanic’s Hull Number Spelled ‘No Pope’

A rumor that originated in Titanic’s hometown of Belfast claimed that when the ship’s hull number, 360604, was viewed in a mirror, it seemingly spelled out 'No Pope.' This story became popular in the devoutly religious Belfast, and before long, many people were asserting that this ominous hull number was the cause of the sinking.

Unfortunately, this story stumbles right at the beginning, considering that the hull number of Titanic was 401, which, when experimented with, seems to approximate the letters 'ROA'—an abbreviation for 'Return On Assets.' A curious tidbit for those who delve into conspiracy theories.

3. Captain Smith Was Planning To Retire After Titanic’s Maiden Voyage

The heartbreaking sorrow of the Titanic disaster is intensified by the notion that its captain intended for the ship’s maiden journey to serve as the crowning moment of his esteemed career. What could be a more fitting farewell to a lifetime at sea than aboard the magnificent Titanic? The tragedy of his abrupt and untimely death makes it all the more devastating. This is a tale that's become entrenched in Titanic folklore, and it’s easy to understand why.

The reality, however, is far less sensational. While it is true that Captain Edward John Smith was nearing the end of his career, there’s no concrete evidence to support the idea that Titanic‘s maiden voyage was meant to be his farewell.

Unlike many of the myths surrounding this story, this particular rumor started even before Titanic embarked on her maiden voyage. In 1911, just before the maiden voyage of Titanic‘s sister ship, the Olympic, The New York Times reported that Captain Smith was expected to retire by year’s end due to his age. The article suggested that Titanic, the younger sister ship, would be commanded by Captain Bertram Hayes. There were even discussions about the appointment of Captain Haddock (not to be confused with the character from Tintin) to lead the ship. By the end of 1911, reports indicated that Smith would indeed command Titanic but only until his planned retirement in the summer of 1912.

As Titanic began its transatlantic journey on April 11, 1912, The New York Times published rumors suggesting that this would be Smith’s final voyage. However, these rumors were quickly refuted by the White Star Line, which stated that Smith would continue commanding Titanic until he could take charge of "a larger and finer vessel"—possibly referring to Britannic, the younger sister ship of Titanic that was still under construction.

It seems plausible that Smith was indeed contemplating retirement, but his widespread popularity led him to stay on longer. Given his fame, it’s not unreasonable to think that the speculation surrounding his retirement actually helped boost ticket sales, creating an added incentive to board Titanic. Unfortunately, we can never know for certain what Smith’s plans were after Titanic‘s maiden voyage. But it’s fair to say that had he wanted to continue his career, opportunities would have been available to him, and there’s no reason to believe Titanic‘s maiden voyage would have been his last.

2. Titanic Sank Because A Coal Bunker Fire Weakened Her Hull

This theory, which has resurfaced recently thanks to a documentary, suggests that a coal fire might have weakened the hull of the Titanic. New photographs reveal a 'smudge' along the starboard hull, the same side that collided with the iceberg. The theory proposes that the fire made the ship’s structure vulnerable, and had it not been for the blaze, the damage from the iceberg collision would have been less severe, potentially preventing the sinking.

Indeed, a coal bunker fire was burning during Titanic‘s maiden voyage. While not unheard of, it wasn’t an unusual occurrence on coal-powered ships. There were procedures in place to address it, and the crew successfully extinguished the fire by the time of the disaster. The issue with this theory lies in the fact that the so-called 'smudge' indicating hull damage is located roughly 15 meters (50 feet) away from where the fire actually occurred. Additionally, the suggestion that cost-cutting measures made the hull unusually susceptible to fire damage is unsupported by any credible evidence. There’s no solid proof that the structural integrity of Titanic‘s hull was compromised.

Interestingly, some theorists propose that the fire may have been more of a help than a hindrance. If some of the starboard bunkers were emptied to manage the fire, this could explain why Titanic didn’t immediately capsize to the starboard side after the collision. Regardless, the damage sustained by Titanic from the collision is consistent with what would be expected for any ship in a similar scenario.

1. J. Bruce Ismay Was a Mustache-Twirling Villain

Since the first dramatic accounts of the 1912 disaster, the story of Titanic has been a magnet for grand narratives of heroes and villains. No one has been more unfairly cast as the villain than J. Bruce Ismay, the chairman of the White Star Line, who was mockingly dubbed 'J. Brute Ismay' by contemporary press. The image of a mustached villain coercing officers into sacrificing safety for speed still endures. But just how accurate is this portrayal?

One of the earliest accusations against Ismay is that he cut corners during the construction of Titanic, prioritizing profit over passenger safety. While it’s true that Ismay was a businessman with a keen interest in keeping costs under control, the evidence shows that he was more than willing to adhere to Board of Trade regulations. He was even open to spending extra on additional lifeboats and newly designed davits to accommodate even more boats should regulations change. It would be too simplistic to suggest that he did this purely out of altruism; it was likely seen as a smart investment for the future. However, it’s also clear that Ismay wasn’t a miser scheming in the shadows to extract every last penny at the expense of safety. After all, making the ship safer and more reliable would ensure greater future profits. Furthermore, attempting to deceive the Board of Trade would have been detrimental to his reputation, which would have hurt his business prospects.

Another accusation often aimed at Ismay is that he intentionally pressured Captain Smith and his officers into exceeding safe speeds, driven by an insatiable desire for fame and glory. However, Ismay himself was a passenger on the ship, which would have made putting the passengers in danger, including himself, utterly nonsensical. Passenger Elizabeth Lines claimed to have overheard a conversation between Ismay and Captain Smith about the ship’s progress, in which Ismay sounded upbeat, optimistic, and content with the current pace. Ismay was heard mentioning the idea of 'beating' the speed record set by the Olympic, which, in hindsight, doesn’t seem particularly strange, considering that both the crew and passengers were aware from the start that Titanic might reach New York a day early. Ultimately, Captain Smith was the one in charge, and as a highly respected and popular figure—nicknamed the 'Millionaire’s Captain'—he was a valuable asset to the White Star Line, and Ismay could hardly pressure him beyond making suggestions.

Some survivors later recalled that Ismay had mentioned the possibility of increasing the ship’s speed later in the journey. This wasn’t uncommon. In calm weather, it was standard for ships—particularly those on their maiden voyages—to travel at maximum speed when possible. However, when Titanic struck the iceberg on the night of April 14, the ship was not yet traveling at full speed. The plan had been to accelerate to full speed on April 15 or 16, depending on the weather conditions. Although Titanic was traveling faster than before, it hadn’t yet reached its maximum speed. Moreover, contrary to popular belief, rather than ignoring iceberg warnings to prioritize speed, the ship’s officers took them seriously, informing the lookouts, and Captain Smith ordered the ship to slow down if the weather worsened.

As for Ismay after the collision, it’s widely known that he was rescued in a lifeboat—an act that haunted him for the rest of his life. What is less known is that the boat he was rescued in was one of the last to be properly launched. It also carried another male first-class passenger and four stowaways. The details of how Ismay ended up in that lifeboat remain a topic of debate, with many arguing that, as a representative of the White Star Line, he should have stayed aboard the ship. However, it’s important to note that up until that moment, Ismay was seen on the boat deck throughout the night, helping women and children into lifeboats. He was even seen encouraging and persuading those who hesitated to get in, instilling a sense of urgency that seemed absent elsewhere. It could be argued that Ismay played a role in saving lives that night.

Whether Ismay is seen as a coward who should never have sought to survive or simply as a man acting on instinct and paying the price for it, the reality is that the often-portrayed image of him as an evil, mustache-twirling villain is far from accurate. He certainly cannot be blamed for the sinking or the tragic loss of lives.