For centuries, numerous authors in English literature have designed extraordinary realms where their stories and characters unfold. These creations often serve as tools for satire, especially under repressive regimes, or simply as a source of pure enjoyment. Here, we present a curated list of the ten most remarkable fictional worlds in English literature.

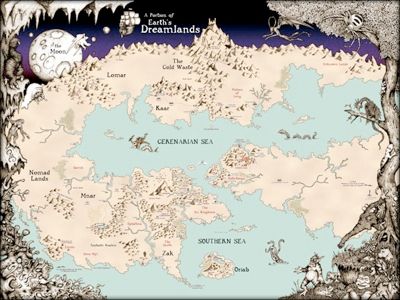

10. Dreamlands H. P. Lovecraft

The Dreamlands, a fantastical realm within H. P. Lovecraft's Dream Cycle, serves as the backdrop for numerous tales by Lovecraft and other writers. This alternate dimension, accessible through dreams akin to astral travel or lucid dreaming, is home to skilled dreamers who can wield significant power and even reside there permanently after death. Entry into the Dreamlands isn't limited to dreams; physical passage is possible but perilous, involving treacherous zones in both the waking world and the Dreamlands. Travelers risk real death but gain the extended lifespan of Dreamlands natives, freeing them from the constraints of earthly sleep. While the term 'Dreamlands' usually refers to the human-accessible dimension, other planets may have their own dream realms, reachable with great difficulty. Time in the Dreamlands moves differently, with hours on earth equating to weeks or more there, allowing dreamers to experience months within a single night. Inhabitants of the Dreamlands enjoy long lives or immortality, barring injury or illness. [Source]

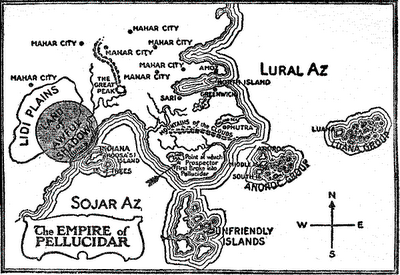

9. Pellucidar Edgar Rice Burroughs

Pellucidar, a fictional Hollow Earth setting created by Edgar Rice Burroughs, the mind behind Tarzan, serves as the backdrop for a series of thrilling adventure tales. In a unique crossover, Tarzan himself ventures into Pellucidar in one of the stories. The narrative begins with mining heir David Innes and his inventor companion Abner Perry, who journey 500 miles into the Earth's crust using an 'iron mole.' Later, the story expands to include Tanar, a native cave dweller, and other surface-world explorers, most notably Tarzan. Pellucidar is inhabited by primitive humans and prehistoric creatures, including dinosaurs. The area where Innes and Perry first arrive is dominated by the Mahars, intelligent flying reptiles resembling pterosaurs with psychic abilities, who oppress local Stone Age tribes. Innes and Perry eventually rally the tribes to overthrow the Mahars and establish a human-led 'Empire of Pellucidar.' While the Mahars are the dominant species in the novels, their influence is limited to a few cities. They enforce their rule through the Sagoths, a race of gorilla-like beings who speak the same language as Tarzan's apes. [Source]

8. Neverland J. M. Barrie

Neverland (also referred to as Never-Never-Land, Never Land, and other variations) is the imaginary island and dream realm featured in J. M. Barrie's play *Peter Pan, or The Boy Who Wouldn’t Grow Up*, his later novel *Peter and Wendy*, and subsequent adaptations by others. In Neverland, individuals stop aging, making it a symbol of eternal youth, immortality, and escapism. According to the 1911 novel, Neverlands exist in children's imaginations, each unique yet sharing a familial resemblance. For instance, John Darling’s Neverland featured a lagoon with flamingos flying overhead, while Michael’s had a flamingo with lagoons flying above it. Time in Neverland is measured by the Crocodile’s clock or the numerous suns and moons, far more abundant than in our world. In *Peter Pan in Scarlet*, Neverland is situated in the Sea of One Thousand Islands, where Peter encounters Lodestone Rock, a magnetic formation that destroys ships like the Jolly Peter and the SS Starkey. [Source]

7.

Shangri-La

James Hilton

Shangri-La, a fictional paradise depicted in James Hilton’s 1933 novel *Lost Horizon*, is a serene and mystical valley nestled in the Kunlun Mountains, overseen by a lamasery. It has come to symbolize an earthly utopia, particularly a secluded Himalayan haven of perpetual happiness. In *Lost Horizon*, the inhabitants of Shangri-La enjoy near-immortality, far exceeding typical lifespans. The term evokes the exotic allure of the Orient and is rooted in the Tibetan Buddhist concept of Shambhala. Since the novel’s publication, numerous modern legends about Shangri-La have emerged. Notably, the Nazis, seeking an ancient master race akin to the Nordic people, sent an expedition to Tibet in 1938. Shangri-La is often likened to the Garden of Eden, representing an ideal paradise hidden from the modern world, and is sometimes used metaphorically to describe an elusive, lifelong pursuit. [Source]

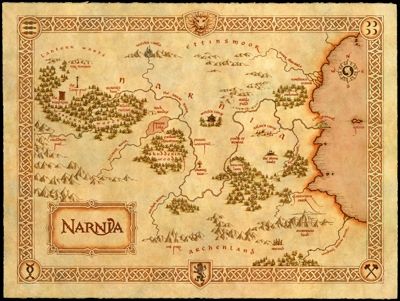

6. Narnia C. S. Lewis

Narnia, a fantastical realm crafted by C. S. Lewis, serves as the central setting for his beloved seven-book series, *The Chronicles of Narnia*. Named after the country where much of the story unfolds, Narnia is a land where animals speak, mythical creatures roam, and magic is an everyday occurrence. The series follows the adventures of humans, often children, who journey from Earth into this enchanting world. According to the series' lore, Narnia was brought into existence by Aslan, a majestic lion, and is inhabited by talking animals and legendary beings. Lewis likely drew inspiration for the name from the Italian town of Narni, known in Latin as Narnia. The landscapes of Northern Ireland, Lewis’s homeland, heavily influenced Narnia’s geography. In his essay *On Stories*, Lewis described how certain views, particularly in the Mourne Mountains, evoked a sense of wonder, as if giants might appear at any moment. Narnia is depicted as a flat world within a geocentric universe, with a domed sky impenetrable to mortals. Its stars are sentient, humanoid entities that perform celestial dances to herald Aslan’s deeds and arrivals. These stars also align to enable seers to predict future events. [Source]

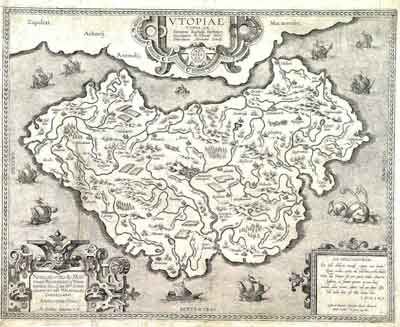

5. Utopia St Thomas More

Utopia, derived from the title of St Thomas More’s 1516 book, refers to an ideal society situated on a fictional Atlantic island with a flawless socio-political and legal system. The term has since been applied to both real-life communities striving for perfection and fictional societies in literature. Often used critically, “Utopia” denotes an unattainable ideal, giving rise to related concepts like dystopia. The word originates from the Greek words “ou” (not) and “topos” (place), suggesting More intended it as an allegory rather than a feasible reality. Interestingly, the similar-sounding “Eutopia,” from the Greek “eu” (good) and “topos” (place), implies a double meaning likely intended by More. However, modern usage often mistakenly equates “Utopia” with a perfect place rather than an impossible one. [Source]

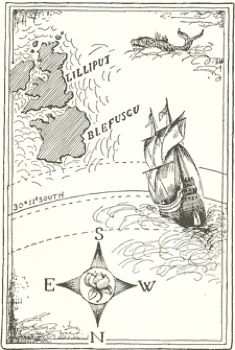

4. Gulliver’s World Jonathan Swift

Lilliput and Blefuscu, two fictional island nations featured in Jonathan Swift’s 1726 novel *Gulliver’s Travels*, are located in the South Indian Ocean and inhabited by people less than six inches tall. Separated by an eight-hundred-yard-wide channel, these tiny societies starkly contrast with the giants of Brobdingnag, whom Gulliver encounters later. In the story, Gulliver is shipwrecked on Lilliput’s shores and captured by its inhabitants while asleep. He learns that Lilliput and Blefuscu are locked in perpetual conflict over the proper way to eat a boiled egg—Lilliputians favor the sharp end, while Blefuscudians prefer the rounded end. The novel also introduces Brobdingnag, a land of giants as tall as church steeples, with strides spanning ten yards. Everything in Brobdingnag, from animals and plants to natural phenomena like rivers and hailstones, is proportionally enormous. For instance, rats are as large as dogs, and flies resemble birds in size. [Source]

3. Middle-Earth J. R. R. Tolkien

Middle-earth is the fictional setting where most of J. R. R. Tolkien’s tales unfold. His stories depict the epic struggle for control over the world, known as Arda, and the continent of Middle-earth. This conflict involves the angelic Valar, Elves, and their human allies on one side, and the malevolent Melkor (or Morgoth), a fallen Vala, along with his followers—primarily Orcs, Dragons, and enslaved men—on the other. Tolkien created numerous maps of Middle-earth and its regions, some published during his lifetime and others posthumously. Key maps appear in *The Hobbit*, *The Lord of the Rings*, and *The Silmarillion*. Tolkien initially suggested that Middle-earth exists on our Earth but in a fictional past, estimating the Third Age ended roughly 6,000 years before his time. However, he later clarified that Middle-earth exists not in a distant past but in a different imaginative realm. [Source]

Notable Omission: Discworld

This article is licensed under the GFDL because it contains quotations from the Wikipedia articles cited above.

Contributors: Beranabus, JFrater

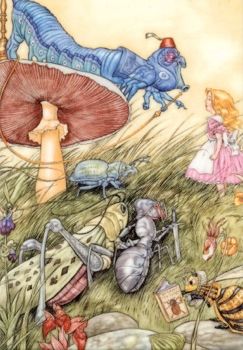

2. Alice’s Worlds Lewis Carroll

Wonderland, the bizarre and whimsical realm from *Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland*, is accessed by falling down a rabbit hole. In this world, animals behave like humans, and concepts like size and time are fluid and relative. While the story begins and ends in the real world, where Alice sits with her sister and later wakes up, Wonderland itself is a dreamlike reflection of reality. Thematically, it represents our world viewed through the lens of a child’s imagination. Similarly, the Looking Glass world mirrors Wonderland, filled with peculiar creatures and surreal events. Entered by stepping through a mirror above Alice’s fireplace, this world is a reversed version of reality—books are written backward, and moving toward a destination requires walking in the opposite direction. The landscape resembles a giant chessboard, with brooks marking the squares and chess rules governing movement. Though slightly less chaotic than Wonderland, the Looking Glass world also serves as a metaphor for the complexities of adulthood, ultimately revealing itself as another dreamscape.

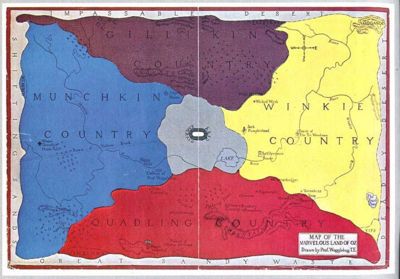

1. The Land of Oz L. Frank Baum

Oz, introduced in *The Wonderful Wizard of Oz*, contrasts sharply with Dorothy’s home in Kansas by being uncivilized, which explains the presence of witches and wizards absent in Kansas. In *Ozma of Oz*, Oz is described as a “fairy country,” a term used to justify its magical elements. The land is roughly rectangular, divided diagonally into four regions: Munchkin Country (often called Munchkinland in adaptations) in the East, Winkie Country (referred to as The Vinkus in Gregory Maguire’s *Wicked* series) in the West, Gillikin Country in the North, and Quadling Country in the South. At the center lies the Emerald City, Oz’s capital and the residence of its ruler, Princess Ozma. Oz is encircled by a vast desert, shielding it from external discovery and invasion. In the first two books, the desert is portrayed as expansive and perilous to travelers, adding to Oz’s isolation and mystique. [Source]